Will self-driving cars reduce energy use and make travel better for the environment?

I started learning driving only three years ago, and – inevitably – failed my first test. Naturally, I was disappointed: but then it occurred to me that I could avoid the whole issue, if only I could get my hands on a driverless car. And this triggered the research question: what would the overall impact on travel demand, energy use and carbon emissions be if driverless cars were readily available to the likes of you and me?

I joined a few like-minded academics in the US – Don MacKenzie and Paul Leiby – to research how the automation of road transport might affect energy use, and to quantify the potential range of these impacts.

We found that a widespread adoption of self-driving vehicles could indeed help to reduce energy consumption in a number of ways. For example, on motorways, automated vehicles can interact with each other and drive very closely as a “platoon”. This can reduce the total energy consumption of road transport by 4% to 25%, because vehicles which follow closely behind each other face less air resistance.

What’s more, when vehicles can interact with each other and road infrastructure – such as traffic control systems – this will smooth out the traffic flow. The result will be less congestion and a reduction in energy use of up to 4%. On top of this, automated “ecodriving” – a driving style which controls speed and acceleration for more efficient fuel use – can reduce energy use by up to 20%.

When you are riding in your self-driving car, obviously you won’t be at the controls, so you will no longer be able to enjoy the rapid acceleration of your driving days – so perhaps the desire for more powerful engines could diminish. And given that vehicle safety is expected to improve dramatically in self-driving cars, some of the heavy safety features could be removed, making cars lighter. Each of these changes could reduce energy use by up to 23%.

The bigger picture

So far, so good – all of these mechanisms improve the efficiency with which a car travels. But, as a society, our interest lies in reducing total energy use, or total carbon emissions – and energy efficiency forms only one half of this picture. Our total carbon emissions also depend on the demand for travel. So, while improving the energy efficiency of cars by automating the driving process will reduce the carbon emissions of individual vehicles, the overall impact of this change will depend on how many people use them.

For instance, consider what would happen if large numbers of people switched to self-driving cars from travelling by train. We generally prefer the privacy and convenience of travelling by car, but using public transport means we can concentrate on other stuff – such as reading a book or getting some work done. A self-driving car offers all of these benefits. As a result, we found that driverless cars could prove so attractive that they increase car travel by up to 60% in the US.

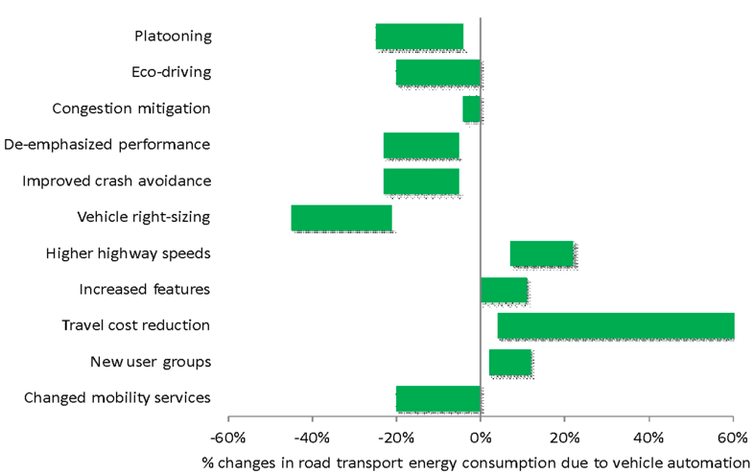

As you can see below, the features of driverless cars may have a range of impacts on energy consumption – both positive, and negative.

Changes in energy consumption, due to various mechanisms facilitated by automation.

Wadud Z, MacKenzie D and Leiby P, Author provided

Self-driving cars could also encourage a completely new group of people to own vehicles – for example, the elderly, the disabled and possibly those too young to drive themselves. This would increase the welfare of that demographic by giving them greater mobility. Yet travel demand, energy use and carbon emissions would all rise: our estimate for the US is an increase between 2% and 10%.

Sharing is caring

But it’s not all bad news: self-driving cars could encourage a move away from current car-owning culture to a car-sharing or on-demand culture. This opens up a few different possibilities. For one thing, by making the per-mile costs more visible to the user, car sharing or automated taxis could reduce travel demand from individuals. Yet these shared automated cars may still travel empty for some parts of their trips, so this option could lead a reduction of energy use between 0% to 20%.

But even greater energy savings are possible if the size of the self-driven shared car is matched to the trip type: for example, if a one-person commute trip is undertaken by a compact car, while for a family leisure trip a medium-sized sedan is used. This approach could reduce energy demand by 21% to 45%.

One thing we haven’t touched in great detail is the potential for self-driving cars to encourage a switch to alternate fuels such as electricity and reduce carbon emissions. Imagine the car dropping you off at your destination and finding a charging point to recharge itself.

So, automation does have the potential to reduce energy use for road transport. But this is not a direct result of automation per se; rather, it is due to how automation changes vehicle design, operations and ownership culture. It’s also interesting that some of the energy-saving benefits of self-driving cars are possible at a lower level of automation, through increased interaction between vehicles and infrastructure.

It is clear that the benefits of self-driving cars will depend on how we use them. The widespread adoption of automated vehicles could well have some unexpected effects, so it’s vital that we find and implement ways to realise the full energy-saving and carbon-reducing potential of self-driving cars. Until then, we’d better keep practising our driving.

Zia Wadud no recibe salario, ni ejerce labores de consultoría, ni posee acciones, ni recibe financiación de ninguna compañía u organización que pueda obtener beneficio de este artículo, y ha declarado carecer de vínculos relevantes más allá del cargo académico citado.