Why is alcohol thought to be relaxing? Victorian and Edwardian explorers might hold the clue

'Captain Scott's last Birthday Dinner', Antarctica, June 6th 1911. Heritage Image Partnership Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

After a long, stressful day, I often find myself sitting down with a bottle of beer or a glass of wine. Such rituals are a sign that the working day is over and that the time for fun and relaxation is here. The problem is that drinking in this way doesn’t work over time. Regular (and excessive) drinking is associated with depression and poor sleep and research shows it may also increase anxiety levels in the long term.

Nevertheless, the idea that alcohol is relaxing remains a powerful myth. With evidence suggesting that many people started to drink more during the COVID-19 pandemic as a way of trying to relax. Delving into the history of alcohol can offer some insights as to why this myth has prevailed.

Throughout history, alcohol has often been used medicinally – and is considered to have many helpful properties, including as an antiseptic and an anaesthetic. I’ve studied how explorers in the 19th and early 20th centuries used drink. Studying travellers can shed light on the scientific and medical understanding of alcohol because, in an era before clinical trials, medical writers drew on the narratives of explorers as evidence about the health effects of different foods and drinks. So their writings can help us learn about past approaches to alcohol and health.

Indeed, many Victorian Arctic explorers drank a “warming” glass of rum at the end of a long days’ sledging. They reported that it helped them to sleep and relax and relieve the tension. Similarly, British travellers in east Africa often drank small quantities of alcohol at the end of a day’s travel, viewing it as a useful “medicine” that helped them to deal with both the effects of fever and the emotional strains of travel. In one travel advice guide published in 1883, George Dobson, a British Army surgeon major, advised that in warm climates “continued labour, such as that of the sportsman and traveller, cannot be maintained for any length of time unassisted by the occasional and judicious use of alcohol”.

Health and balance

Initially and in small doses, alcohol seems to act as a stimulant, which makes your heart beat faster and gives you more energy. Soon, though, it acts as a depressant, inhibiting the action of the central nervous system, which slows your thinking and reaction times. These health effects were particularly important in early 19th-century medicine, as some medical theorists saw the body as a system that had to be kept in balance. And stimulants or depressants were seen as an important way of restoring balance if someone was unwell.

In time, these views became increasingly unpopular among scientists and medics and were replaced by theories of disease that sought to chart more specific causes of infection. For instance, “germ theory”, which was first proposed in 1861, showed that many illnesses were caused by microbes rather than climate. Similarly, British medics were becoming increasingly interested in the role of mosquitoes in spreading malaria. Such developments led to new medical approaches which sought to prevent and treat diseases common in warm regions.

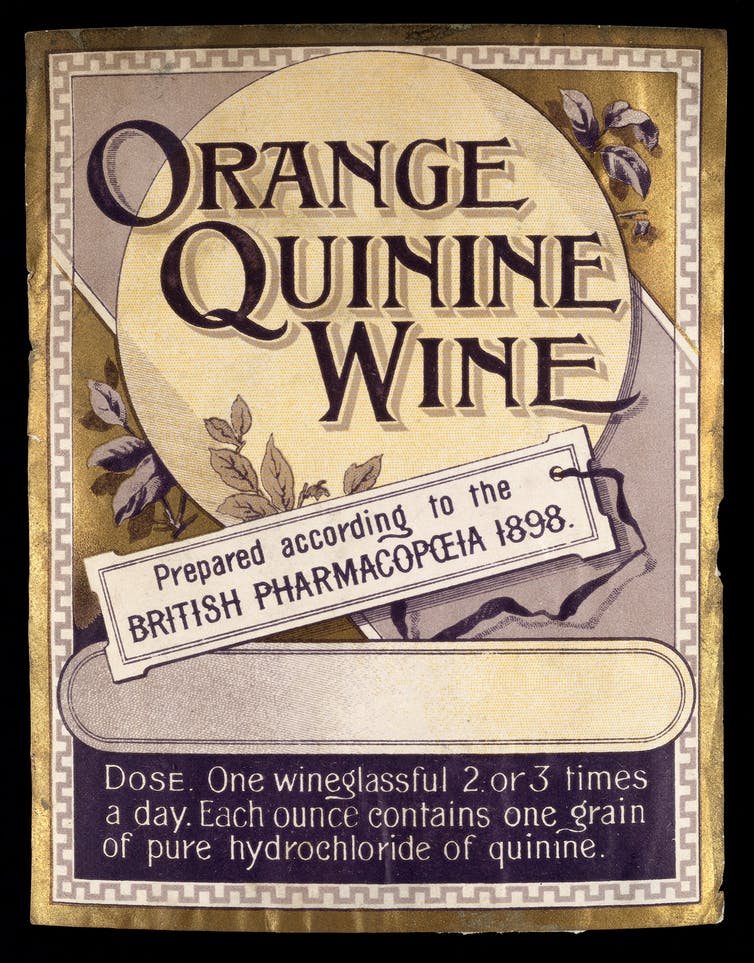

Alcohol could also be used as a mixer for other drugs as this advert for ‘Orange Quinine Wine’ shows.

Wellcome Collection

Criticism of drink

But changing medical attitudes towards diseases were not the only factor in the decline of medicinal drinking on expeditions. The growing criticism of expeditionary drinking was also the result of changing social and medicinal attitudes towards alcohol. This was largely because of the temperance movement, a campaign rooted in evangelical Christianity that sought to discourage (and sometimes outright ban) the sale of alcohol.

Even those who viewed moderate drinking as acceptable began to worry that it might actually be more dangerous in climatic extremes. For instance, the National Arctic Expedition (1875-1876) was criticised for issuing a rum ration, with suggestions it had contributed to an outbreak of scurvy, which allegedly manifested itself first among the expedition’s heavy drinkers.

Drinking Brandy in Antarctica: An Image from the British National Antarctic Relief Expedition, 1903.

Scott Polar Research Institute: ref P2007/24/6

Such criticisms meant that explorers went to growing efforts to emphasise that their drinking was moderate and “medicinal”. They often did so by only drinking certain kinds of alcoholic beverages that, they argued, had greater medicinal qualities. This normally meant brandy, champagne, or certain kinds of wine. But there were fierce disagreements between medics about which drinks were most healthy.

Indeed, many of these drinks were viewed as medicinal for no reason other than the fact that they were expensive. Today, such drinks are seldom viewed as medicinal – but medical concerns with the effects of different alcoholic drinks, have not gone away. And, much like their Victorian counterparts, many contemporary medics have suggested that certain kinds of drinks are healthier than others.

Stimulants: alcohol or caffeine

As recent research by my colleague Kim Walker and I shows, stimulants (including alcohol) remained a popular medicine for European travellers in Africa into the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In part this was because they were relatively cheap, easy to administer, and produced discernible effects on the mind and body of the drinker. They were also believed to remedy the enduring belief that warm climates were physically damaging and psychologically depressing.

In the same 1883 travel guide, Dobson complained of “the depressing effects of the climate” to support his alcohol prescription. Consequently, some travellers saw alcoholic drinks as useful stimulants to help combat these effects. Even those who opposed expeditionary drinking still saw stimulating drinks as important, but prescribed “a cup of fragrant coffee” instead.

Medical understandings of drinking have changed considerably over the last 150 years. But studying how Victorian and Edwardian explorers approached alcohol also shows important continuities. Then, as now, drinking practices are shaped not just by medical knowledge but also by cultural attitudes towards different drinks and the environments we consume them in.

Edward Armston-Sheret received funding from the Arts and Humanities Research Council via the techne DTP, the Royal Historical Society, and the Historical Geography Research Group of the RGS-IBG.