Why are young Australians turning their back on the car?

All over the developed world young people are turning their back on the car. Why is it happening in Australia? AAP/Julian Smith

Australians have long had a love affair with the car. Car ownership and use has increased every decade since its introduction to Australia. The car has fundamentally shaped the urban form of Australian cities – not just through investments in roads, highways, bridges and tunnels but also by facilitating the spread of Australia’s suburbs and activity centres. The car has provided significant social and economic benefits and helped generations of young adults break free from their parents.

Recently, however, Australia’s love affair with the car has begun to cool. For the first time in Australia’s history, young adults are becoming less likely to get a car license than their parents. Where baby boomers couldn’t get enough of their cars, an increasing number of millennials (the generation born from the mid-1980s onwards) have had enough of them.

Putting the brakes on driver licensing

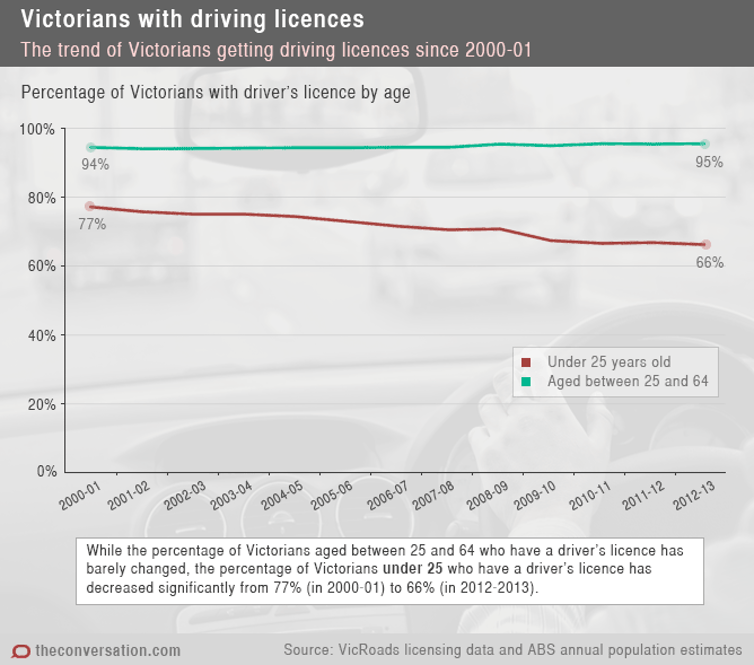

In Australia, the decline in driver licensing has been recorded in New South Wales and Victoria. Australia is one of the few countries that doesn’t compile national licensing rates. In Victoria, the decline has been slow but steady. Licensing rates for people under 25 have dropped from 77% to 66% since 2000-01.

Australia isn’t alone in this trend. A review of youth licensing rates in 13 countries found declines in the US, Canada, UK, Japan and much of Europe.

All over the developed world millennials are turning their back on the car. But why is this happening and what does it mean for Australia’s future?

What’s driving this trend?

Research into this trend is still unfolding, but a range of explanations are being explored. Recent changes in driver licensing regulations cannot be overlooked. All Australian states and territories have gradually introduced more restrictions on learner permits and driving licenses. Most notably, depending on the jurisdiction, millennials are now required to log up to 120 hours of supervised driving before applying for a provisional license.

How many baby boomers would have put off getting a license if they were expected to spend that much time driving with their parents? However, this explanation cannot fully explain this shift. In Victoria, the decline in youth licensing was documented at least as far back as 2000, seven years before the 120 hours requirement came into force.

So if driver licensing regulations aren’t all to blame, what else could be turning millennials away from the car? One complex but significant shift in recent years is how the life course of millennials has changed compared to previous generations.

In the past, many young Australians quickly transitioned from secondary school to full-time work, marriage, mortgage and children. Today’s young Australians are more likely to attend tertiary studies, work part-time, live with parents and delay marriage, mortgage and children. All of these changes mean that young adults have less need for a car in their teens, but also have less money to pay for one.

This raises the question of whether the cost of motoring has discouraged young adults from getting a car. This is a more complex issue as even though fuel prices have certainly increased in recent years, overall the relative cost of motoring has actually decreased.

Finally, there’s some suggestion that the attitudes and lifestyle of millennials have caused a cultural shift where the car is no longer king. The car has long held a cherished place in Australian culture, especially for the baby boomer generation. But recent research suggests that for millennials, the car is less a symbol of status and pride and more a symbol of adult responsibility – a responsibility that not everyone is ready for.

In the words of one 22-year-old research participant:

A car to me symbolises commitment, financial responsibility and to some extent becoming an adult.

Instead, it has been suggested that gadgets and mobile phones have replaced the car as the new status symbol, hobby and means to keep in touch with friends.

There is no doubt that these technologies are a major part of the lifestyle of many millennials, but the jury is still out as to whether technology is reducing the need for face-to-face contact (and therefore reducing the need for a car). Preliminary research suggests that young people who maintain frequent contact with friends through technology are actually more likely, not less, to see their friends in person.

Where to from here?

There are many factors that influence how young adults travel, and further research is needed to better understand these decisions.

There are still important questions that need to be answered. Are these young adults forgoing cars entirely, or merely delaying a few years before they get behind the wheel? Are young adults actively choosing a more sustainable lifestyle, or are they being forced out of cars due to unwanted circumstances? The societal benefits of fewer cars are obvious, but are car-less millennials suffering significant negative consequences?

We can react to this change in car use in one of two ways. We can sit in the back seat and passively enjoy the benefits of fewer cars on the road, slowing the growth of emissions and congestion by a small amount. Or we can take the wheel and actively support this change, putting in place policies and structures to support and encourage young adults who are deciding between L-plates or a new bicycle, car keys or an annual public transport pass.

Once someone shapes their life, work and home around the car it is far, far harder to persuade them not to use it.

Alexa Delbosc has received research funding from Public Transport Victoria and Metro Trains Melbourne. She is a member of The Australian Institute of Traffic Planning and Management.