Where drivers don’t mean to speed, it’s no good just fining them

Blaming motorists for their speeding may at times be undeserved. We have recently shown that, rather than intentional wrong-doing by drivers, cognitive factors can explain speeding behaviour.

Policies and enforcement measures to tackle speeding rely on the idea that driving too fast is always intended by drivers as a result of their attitudes (lack of consideration of the possible consequences) and their willingness to act inappropriately. But speeding is not always a deliberate action.

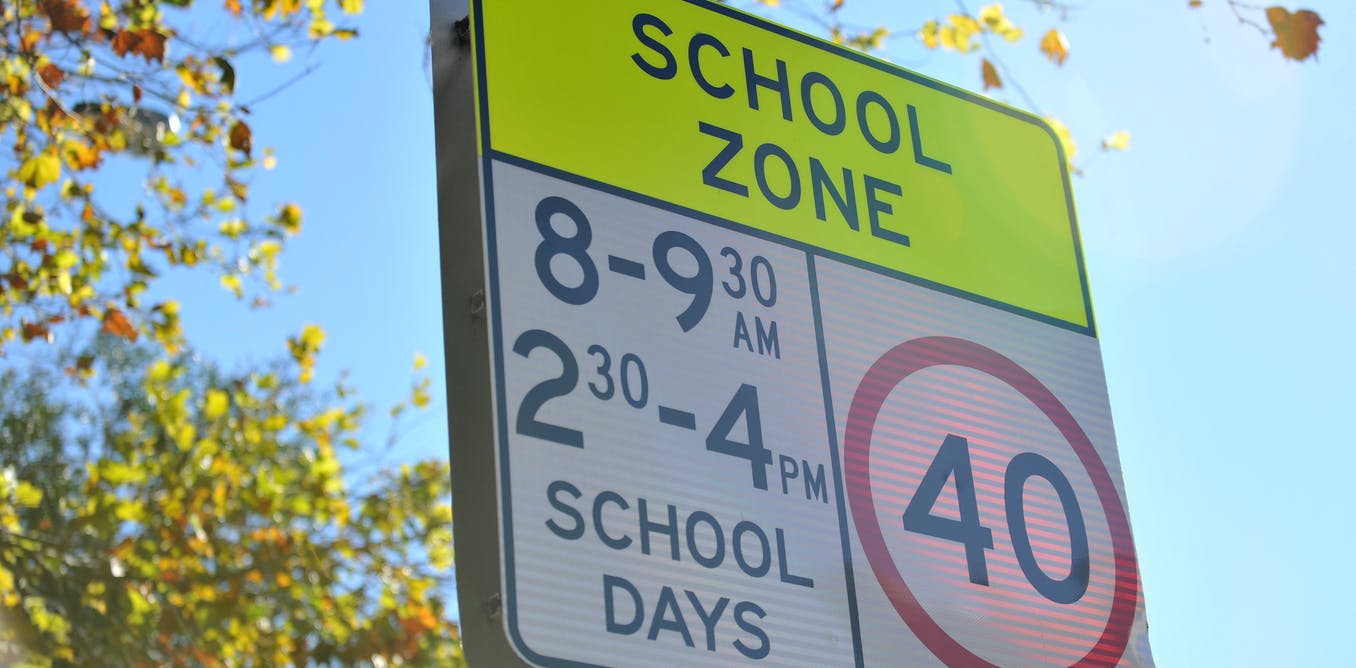

School zone risks require lower speed limits

It is standard across Australia to find variable speed limits within school precincts. At times when children are travelling to and from school, a substantially lower limit applies, usually reducing a general urban speed limit to 25-40 km/h in the school zone.

It is important for drivers to comply with lower speed limits within school zones given the increased activity by pedestrians (especially children) in these areas. This creates increased risks and greater consequences of a collision involving pedestrians.

Despite this, speeding in school zones remains common. In response to the “significant risks associated with low-range speeding”, police and policymakers have relied on enforcement, harsher penalties and education to reduce speeding behaviour. However, in school zones this often does not work.

Why might drivers speed in school zones?

We argue that drivers may recognise that they are in a school zone and slow down at the entry point when they see the speed limit signage and signals, but they forget to drive slowly as they transit the entire school precinct.

So how do drivers forget they’re in a school zone? We tend to think of memory as the recollection of past events, but memory also plays a part in planning and deciding on future behaviour. This is prospective memory – the memory for future intentions – and it is very important for our everyday lives.

But prospective memory is not foolproof. Errors can occur where individuals forget to perform an intended task. Typically this happens when the “normal” flow or sequence of behaviour is interrupted.

A failure to remember to complete an intended behaviour can have serious, unsafe consequences. For example, in commercial aviation interruptions to pre-flight procedures and subsequent prospective memory errors have been shown to contribute to planes crashing. Mid-procedure disruptions have resulted in physicians leaving instruments or sponges in patients following surgery.

We propose that if drivers are speeding within a school zone, their behaviour may be the result of a failure of prospective memory caused by some interruption. A major interruption in some school zones occurs when drivers are required to stop at traffic light intersections. Traffic light “interruptions” may lead to prospective memory error in the following ways:

The ‘green means go’ signal may cause some drivers to resume travelling at their usual speed.

Wikimedia Commons/Jacklee, CC BY-SA

Because of the relative abruptness of the traffic light change from green to amber to red, drivers may have little opportunity to encode the future intention to resume travelling at the reduced school zone speed limit. This memory error can be further promoted if additional distractions attract attention – for example, pedestrian movements or the presence of other vehicles, as well as in-car events such as a radio broadcast or conversation with a passenger. Prospective memory suffers when attention is divided.

Cues in the environment that are associated with the resumption of driving – for example, the change from red to a green traffic light, a clear path ahead to continue their journey – may lead an individual to accelerate to the speed at which they would typically drive when school zone hours do not apply. The driver has simply failed to recall the need to resume the interrupted and deferred task of driving at the lower speed limit.

On driving resumption, there are scant cues in the environment to prompt memory retrieval for the deferred task of travelling at a reduced speed. If the route is regularly travelled, the available cues probably suggest habitual driving at the usual (non-school zone) speed.

What did our study find?

We found that when a driver was able to choose the speed at which they travelled – that is, where the road was clear and there were no vehicles ahead to slow them down – then if they had been interrupted by stopping at a red traffic light, they resumed driving at higher speeds. These speeds related to the normal speed limit, rather than the temporary lower limit.

When there was no traffic light interruption, drivers progressed through the school zone at slower speeds, which were closer to the school zone limit.

When we placed a reminder cue after the traffic light – simply signage featuring twin amber flashing lights and a sign “Check Speed” – then drivers were able to correct (or fully avoid) a prospective memory error. The driving speeds on resumption were fully compliant with the school speed limit.

What this research means

We are not arguing that it is invalid to treat speeding behaviour as an intentional act. A number of researchers have found that drivers do deliberately and consciously intend to speed.

What we are arguing is that, in some circumstances, the way the road infrastructure is designed may encourage and prompt motorists to engage in otherwise avoidable illegal speeding behaviour. We have shown that such a phenomenon can occur when traffic lights interrupt drivers in school zones.

Drivers appear not to notice their behaviour. But if reminded to think about their speed, they adopt a correct, safe speed.

The same cognitive process may also apply in circumstances where drivers fail to slow at speed cameras sites, at roadworks sites or in the transition from rural to urban speed zones.

A serious attempt to create a “Safe System” of road use must take this evidence into account. For example, we have shown that placing reminder cues downstream from a known point of interruption can be an effective low-cost solution that eliminates most speeding in high-risk locations.

Bree Gregory will present this research at the Australasian Road Safety Research, Policing and Education Conference in Melbourne, November 12-14.

Ian J. Faulks MAPS is an NRMA-ACT Road Safety Trust Research Scholar, and receives funding from the Trust. He is an Honorary Associate with the Department of Psychology, Macquarie University. He is a member of the Australasian College of Road Safety.

Bree Gregory et Julia Irwin ne travaillent pas, ne conseillent pas, ne possèdent pas de parts, ne reçoivent pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'ont déclaré aucune autre affiliation que leur poste universitaire.