Truthfulness: The Psychology of Direct-to-Consumer Life Applications – ThinkAdvisor

What You Need to Know

Most consumers feel uncomfortable about lying.

They may be more comfortable about lying to people who seem farther away.

Beliefs about social norms could influence how much, or how little, information applicants share.

Here’s the second in a series of three articles about what behavioral science can tell us about the life insurance application process.

This article focuses on factors that influence the likelihood that life insurance applicants will give complete, accurate answers to underwriters’ questions.

One might think that direct-to-consumer applications would return higher disclosure rates than adviser led applications.

As insurer representatives do not earn a sales commission, there would essentially be no conflict of interest when a representative collects application information. The incentive is to collect accurate information.

However, other psychological factors could influence disclosure rates over the telephone or online.

1. The Possibility of Getting Caught

Does involving an insurer-representative in telephone interviews objectively increase the chance of identifying non-disclosure?

If this is so, insurers could rectify inaccuracies or even dissuade potential non-disclosures up front. This would reduce the utility (value) of intentional dishonesty for applicants.

Psychologists have found that people trying to deceive without being detected inadvertently give certain physical signals. Increases in heart rate driven by nervousness can lead to changes in speech and mannerisms.

However, even though deception is part of everyday life, humans can be poor at picking up the signals.

Indeed, studies have found that people detect deception only slightly more than about half the time, which is not much better than what would be expected by chance.

When an applicant meets an interviewer face-to-face, the interviewer can see who the applicant is.

Over the telephone, applicants remain relatively anonymous.

A telephone interviewer can’t, for example, visually check to see whether the applicant has given reasonable responses to questions about matters such as height and weight. It is unlikely, therefore, that any objective possibility of getting caught mis-disclosing or non-disclosing to a telephone interviewer might be a deterrent to not being truthful.

2. Discomfort About Deception

While the objective possibility of getting caught is an unlikely deterrent, the subjective side of deceiving others may be one.

Most people, when they tell an untruth, notice that their hearts beat faster and that their blood pressure rises. They feel a little nervous, fearful, and guilty.

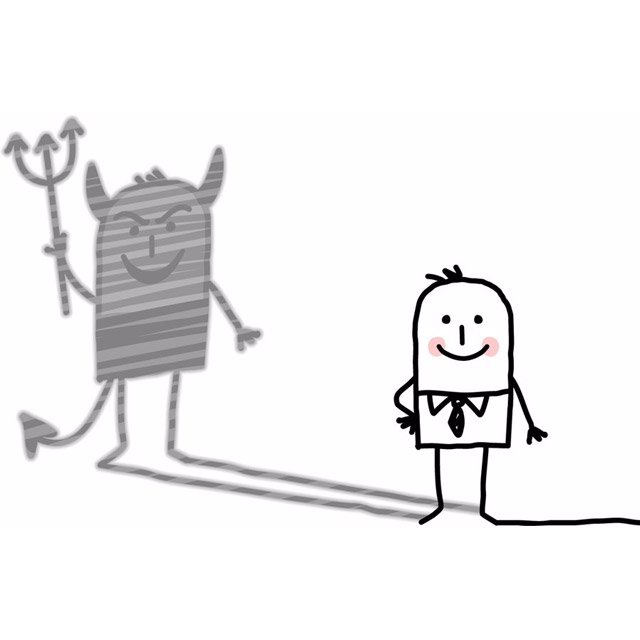

Deliberate lying makes most people feel uncomfortable.

This can especially be the case when the people who are lying think they may be giving off cues that betray the deception, when they are less in control of the conversation, or when they believe a real person will suffer consequences as a result of a lie.

Reducing the psychological distance between the deceiver and the deceived could heighten the deceiver’s uncomfortable emotions.

This is indicated by empirical evidence.

In 2012, Leanne Ten Brinke and Stephen Porter reported that in discussion deceivers will often use language to attempt to distance themselves from the deceit, to make it psychologically easier to deceive.

Deceivers may do this by, for example, using fewer personal pronouns, and more tentative words, such as “maybe.”

The presence of another human, as in face-to-face or telephone interviews, makes the identity of the victim of a deception more concrete and immediate and diminishes the applicant’s control over the process.

Research shows that participants, when given a choice between whether to deceive a partner in an experiment via texting or face-to-face encounters, were more likely to deceive in a text.

This suggests that people may find it easier to deceive through channels that provide participants with greater psychological distance.

3. Time

Another important factor is “asynchronicity.”

An asynchronous application channel, such as a process that requires a consumer to mail a paper form to an insurance company, separates the communicator and the receiver of the communications in time and space.