The Corwin Getaway Is One That Got Away

Low-slung, mid-engined, and just 11 feet long, the Corwin Getaway way back in 1969 forecasted the arrival of sporty runabouts like the later Fiat X1/9 and Toyota MR2, and it still looks fresh today. Some LED lighting and an EV powertrain and this could be the product of a current Silicon Valley startup. Instead, only a single prototype exists, making the Getaway one of the great what-might-have-been stories of automotive history.

courtesy of The Petersen museum

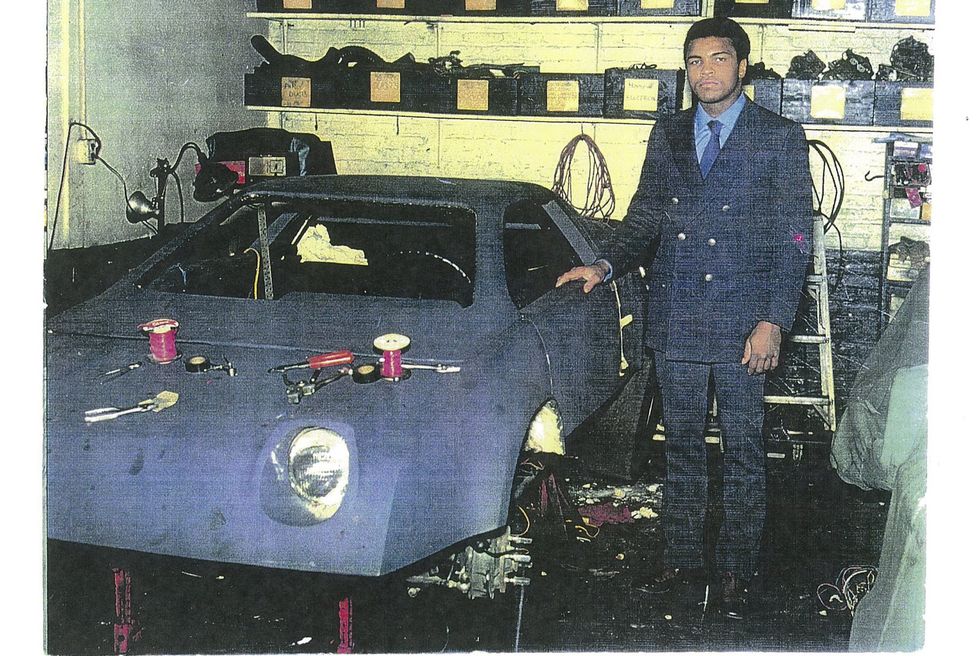

Flashback to August 1965: The Watts neighborhood in Los Angeles was boiling with racial and class tension. The spark was the arrest of 21-year-old Marquette Frye, the tinder a community simmering with resentment at police mistreatment. Cliff Hall, a Black photographer whose work took him all over L.A., from the moneyed heights of Beverly Hills to the working class struggles in South Central, believed the solution to inequality could be found in industry. He hoped to be the first Black designer to create a car built by and for the Black community, and the Getaway would be that car.

Cliff Hall

courtesy of The Petersen museum

A former U.S. Navy man, Hall served from 1943 to 1946, where he’d learned electronics. Returning to civilian life, he trained at the just-founded Fred Archer school of photography in Los Angeles. By 1965, he was the chief photographer of the Los Angeles Sentinel, one of the oldest and largest-circulation Black newspapers in the Western U.S. His career as a photographer would span decades, and he had a gift for capturing the moment.

But Hall didn’t just have an exceptional eye, he had a restless intelligence. By all accounts he practically fizzed with possibilities, ideas popping off him like sparks out of a crackling fire. Among other inventions, he built his own mobile photo development studio in a van, which allowed him to shoot an event and then present the photos immediately afterward.

“What motivates me more than anything else is that I like to create,” he told the Times. “I like to take raw material and turn it into something of value. Design is a feeling—something right in my fingertips that has to be released.”

courtesy of The Petersen museum

It was in his blood. His grandfather was a watchmaker, and his two maternal grand-uncles had built cars and even an airplane in the 1920s. Hall was a natural creative genius, and when he turned his talents toward building a car, few doubted that he would succeed.

The concept for the Getaway was a small, efficient runabout, ideal for busy Los Angeles traffic. The Getaway would be inexpensive but fun, within reach of younger buyers. Fifteen years later, Toyota would launch the original, wedge-shaped MR2 on essentially the exact same principles.

The Corwin name came from Louis Corwin, a local importer of Panasonic electronics. As an early adopter who could see where the Japanese manufacturing industry was going, Corwin clearly saw the potential in Hall’s ideas. He invested $100,000 toward development.

Specs

Underneath, the Corwin Getaway is a square-tube chassis with a fiberglass body. The engine is a Subaru flat-four of unknown origin—Hall reportedly pulled it from a junkyard—good for approximately 78 horsepower. The car is incredibly compact, two feet shorter than a Pontiac Fiero, and with the wheels pushed to the corners.

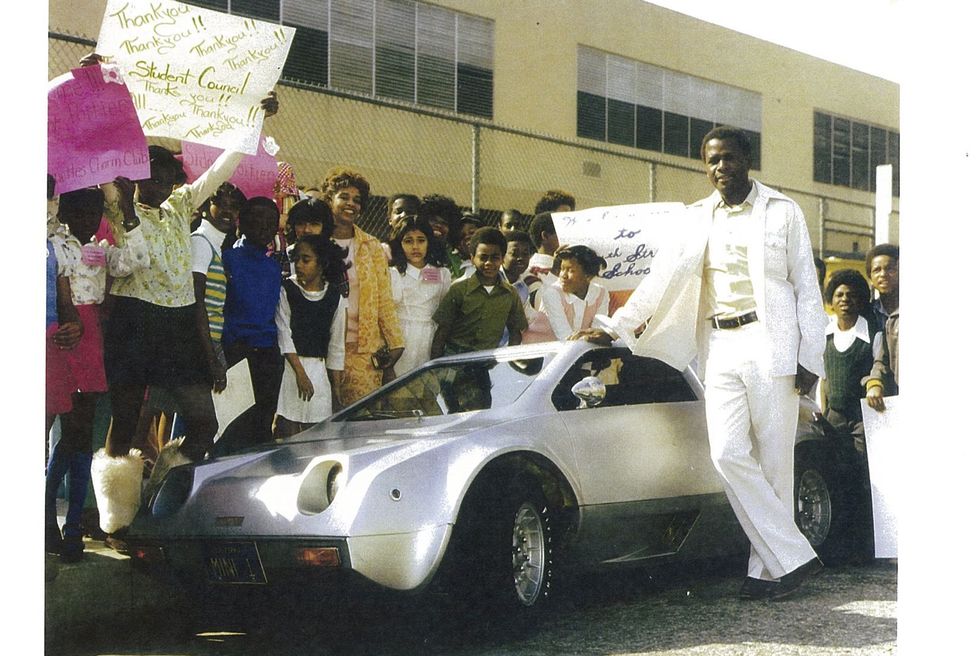

As a photographer, Hall regularly covered the celebrities of the day. Stars including Sidney Poitier and Marvin Gaye supported the Getaway project when it was shown at the Los Angeles auto show in 1970, as did Muhammad Ali.

courtesy of The Petersen museum

But as is often the case in Southern California, there was a huge gap between the dream and the reality. Building a successful prototype is hard enough, but raising the millions needed to build a factory was a much higher hurdle. Hundreds have tried and failed to go the distance, from the DeLorean DMC-12 to the recent Solo electric three-wheeler. Hall’s Getaway ran and drove as a proof of concept, but it couldn’t get traction to make it into production.

A Home at the Petersen Museum

When the Petersen Automotive Museum opened in December 2015, Hall was invited to display his creation as a symbol of Los Angeles car culture and innovation. Petersen curator Leslie Kendall says he was aware of the car because of its L.A. auto show appearance and that it began a relationship between the museum and Hall. A few years later, Hall entrusted his beloved Getaway prototype to the Petersen, and work began on bringing it back to its former glory.

courtesy of The Petersen museum

The work was done by restorer Bodie Stroud, who had previously restored the Petersen’s three-wheeled Davis Divan—another L.A.-based automotive oddity. Everything was complete, as Hall had cherished his prototype, but the Getaway still got a solid overhaul.

courtesy of The Petersen museum

While Hall himself expressed frustration that he never found the support needed to turn the Getaway into a production car, he was delighted to see his legacy preserved. Hall died in 2020, at the age of 94,

But he leaves behind an incredible body of work, including the Getaway. From a time and a place marked by struggle, the Corwin Getaway is a symbol of unbridled creativity and hope.

“The importance of the car is not as an artifact, but the way it represents an idea,” Kendall says, “We had to make it new again, bring it back. It was one of my most rewarding days at the museum.”

The Corwin Getaway can be seen at the Petersen Automotive Museum in Los Angeles as part of the vault tour.

Contributing Editor

Brendan McAleer is a freelance writer and photographer based in North Vancouver, B.C., Canada. He grew up splitting his knuckles on British automobiles, came of age in the golden era of Japanese sport-compact performance, and began writing about cars and people in 2008. His particular interest is the intersection between humanity and machinery, whether it is the racing career of Walter Cronkite or Japanese animator Hayao Miyazaki’s half-century obsession with the Citroën 2CV. He has taught both of his young daughters how to shift a manual transmission and is grateful for the excuse they provide to be perpetually buying Hot Wheels.