The 2022-23 Budget: Health Care Access and Affordability – Legislative Analyst's Office

Health Care Access and Affordability. Health care access and affordability are a challenge for many Californians. Notably, roughly 3.2 million Californians lack access to comprehensive health insurance. Even those who do have health insurance can struggle with health care costs that can consume a large portion of their annual income. These challenges have prompted recent actions by the Legislature and a number of additional proposals in the Governor’s budget as well as other issues for the Legislature to consider during the current budget cycle.

Report Focuses on Issues Related to Health Insurance Coverage and Health Care Costs. While there are a broad range of issues impacting both the affordability and access to quality health care services, this report focuses on access to health insurance coverage and the affordability of health care costs Californians face. In this context, we first provide an assessment of various Governor’s budget proposals intended to improve health care access and/or affordability. (We provide an assessment of proposals potentially affecting access through other means, such as by increasing Medi‑Cal provider payment levels, in other budget publications.) We then discuss issues for the Legislature to consider as it evaluates options to improve the affordability of health insurance coverage offered on the state’s health benefit exchange—Covered California. Finally, we conclude with a brief discussion of some key access and affordability challenges that likely would remain even if the Legislature approves the Governor’s proposals and takes action to improve affordability within Covered California.

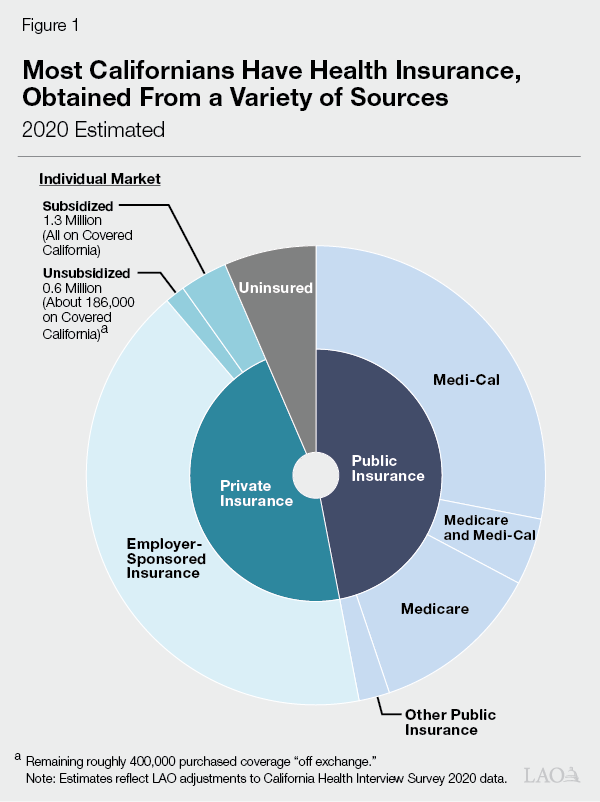

Most Californians Have Health Insurance… As shown in Figure 1, we estimate that most Californians—92 percent—have health insurance coverage. (Compared with other states, California’s rate of insurance is roughly in the middle—some states have higher rates of insurance, while others have lower rates of insurance.) Employer‑sponsored insurance is the most common source of coverage. Major public health insurance programs, including Medi‑Cal, the state’s Medicaid program which covers low‑income people, and Medicare, the federal program that primarily provides health coverage to the elderly, also cover large portions of the state’s residents.

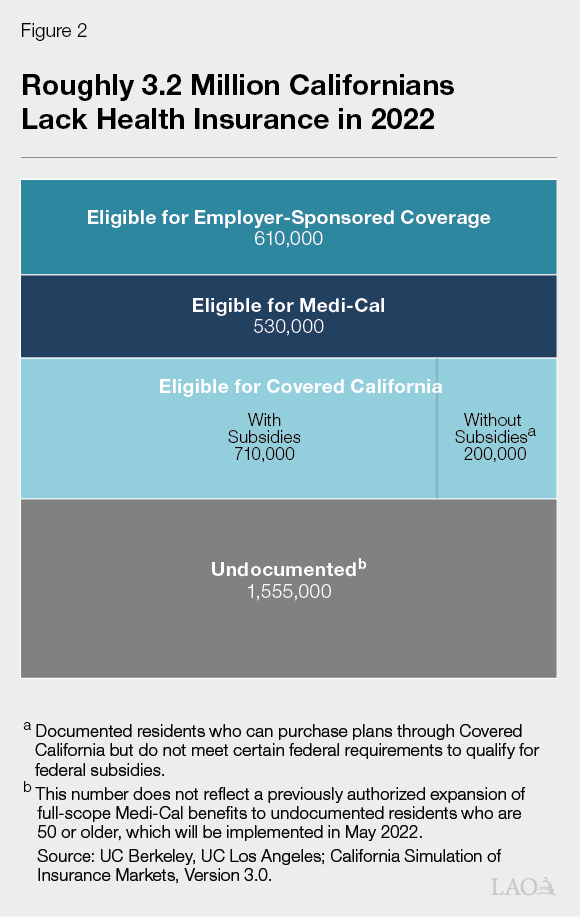

…But an Estimated 3.2 Million Californians Lack Comprehensive Insurance. While most Californians have comprehensive health insurance, an estimated roughly 3.2 million people (about 8 percent) in the state lack such coverage in 2022—including people who are uninsured or have “restricted‑scope” Medi‑Cal that only covers emergency‑ and pregnancy‑related health services. However, these figures do not reflect a previously approved expansion of comprehensive Medi‑Cal coverage to undocumented residents who are 50 or older which will go into effect in May 2022. In addition, the estimate does not reflect impacts of a federal policy change regarding Medi‑Cal enrollment during the COVID‑19 national public health emergency (which likely increased insurance coverage). As shown in Figure 2, the majority of uninsured Californians are undocumented residents, followed by individuals who are eligible for but not enrolled in insurance from a variety of sources.

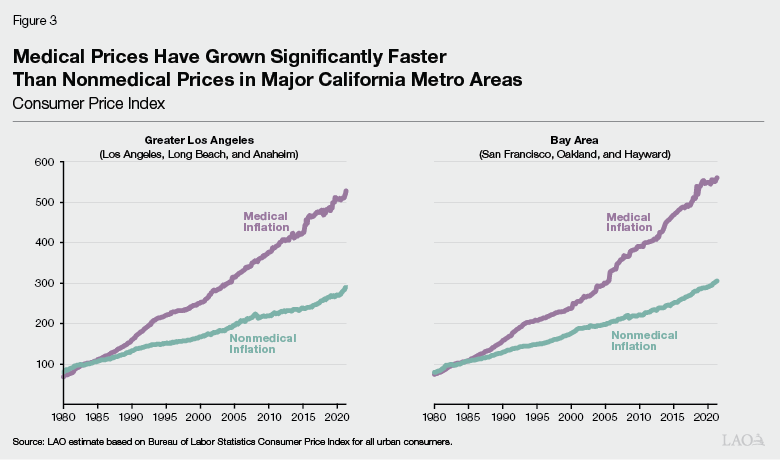

Affordability of Health Care Remains a Challenge. Over the last several decades, health care costs have grown significantly. To a significant degree, this cost growth has been driven by growth in health care prices. As Figure 3 shows, medical inflation in major California metro areas has far outpaced inflation for other goods and services in recent decades, reducing what Californians can afford to spend on these other goods and services. While other expenditures such as housing have a greater impact on California’s cost of living, Californians need to balance health care costs with these other expenditures. According to a survey conducted between November 2020 and January 2021, roughly 82 percent of Californians stated that it was either very or extremely important for the Legislature and Governor to make health care more affordable. In the same survey, roughly half of Californians decided to delay, skip, or reduce their utilization of health care in the prior 12 months due to costs. Of those who made such decisions, 41 percent stated that the steps they took to reduce costs had a negative impact on their health.

Expand Full‑Scope Medi‑Cal Coverage

to Remaining Undocumented Populations

Background

Historically, Undocumented Residents Were Eligible Only for Restricted‑Scope Medi‑Cal Coverage. Medi‑Cal eligibility depends on a number of individual and household characteristics, including, for example, income, age, and immigration status. Historically, income‑eligible citizens and immigrants with documented status generally have qualified for comprehensive, or full‑scope, Medi‑Cal coverage, while otherwise income‑eligible undocumented immigrants have not qualified for full‑scope Medi‑Cal coverage. Up until recently, all undocumented residents who met the income criteria for Medi‑Cal have been eligible only for restricted‑scope Medi‑Cal coverage, which only covers emergency‑ and pregnancy‑related health care services. The federal government pays for a portion of undocumented immigrants’ restricted‑scope Medi‑Cal services according to standard federal‑state cost‑sharing rules.

State Has Expanded Full‑Scope Medi‑Cal Coverage to Many, but Not All, Otherwise Income‑Eligible Undocumented Residents. The state has taken steps to expand eligibility for full‑scope Medi‑Cal coverage to otherwise eligible undocumented residents in various age groups. First, in 2016, the state expanded full‑scope Medi‑Cal coverage to otherwise eligible undocumented children from birth through age 18. Then, in 2020, the state expanded full‑scope Medi‑Cal coverage to otherwise eligible undocumented young adults ages 19 through 25. Most recently, as part of the 2021‑22 budget package, the state passed legislation to expand eligibility to undocumented residents who are 50 or older beginning May 1, 2022. The costs of these expansions are paid almost entirely by the state because the federal government only shares in the cost of restricted‑scope services. Accounting for these recently enacted expansions, undocumented adults who are between the ages of 26 and 49, inclusive, are the remaining undocumented population eligible for only restricted‑scope Medi‑Cal. Once the 50‑and‑older expansion is fully implemented, we estimate that a little over 1 million undocumented immigrants will have full‑scope Medi‑Cal coverage.

Proposal

The Governor proposes to expand full‑scope Medi‑Cal coverage to income‑eligible undocumented residents aged 26 through 49 beginning no sooner than January 1, 2024. Due to past expansions, this proposal would effectively provide universal access to Medi‑Cal regardless of immigration status. The administration estimates that in 2023‑24, the first year of the expansion, 714,000 undocumented residents between the ages of 26 through 49 would enroll in Medi‑Cal and that this would increase to 764,000 residents at full implementation. Due to the proposed implementation date, there is no budgetary impact in 2022‑23. The administration estimates that the expansion would result in costs of $613.5 million General Fund ($819.3 million total funds) in 2023‑24 and $2.2 billion General Fund ($2.7 billion total funds) annually at full implementation. The growth in projected spending primarily is due to annualizing half‑year costs in 2023‑24 and projected gradual increases in the uptake of In‑Home Supportive Services among beneficiaries, along with gradual increases in caseload.

Assessment

Proposal Consistent With Statutory Goals and Recent Legislation. The Governor’s proposal is consistent with past legislative efforts to expand Medi‑Cal coverage to younger and older undocumented residents. It also further the goals established in Chapter 34 of 2018 (AB 1810, Committee on Budget) which, among other goals, declared an intent that all Californians (1) receive high‑quality health care regardless of various factors including age and immigration status and (2) have access to affordable health coverage.

Proposal Would Significantly Reduce Number of Californians Who Lack Comprehensive Insurance. If the administration’s caseload assumptions are correct, this proposal would substantially reduce the number of Californian’s who do not have access to comprehensive health insurance. Using the administration’s assumptions for this proposal, and assuming that 235,000 undocumented residents who are 50 or older will enroll in Medi‑Cal once they are eligible this May under previously enacted legislation, we estimate that the number of Californians who lack comprehensive health insurance would go down to about 2.2 million people following the proposal’s full implementation, which is roughly 1 million lower than the current level of about 3.2 million people.

Continuing to Evaluate Administration’s Caseload and Cost Estimates. Due to the availability of data at the time of this analysis, we have not yet evaluated the reasonableness of the administration’s estimates of the caseload and cost impacts of this proposal. Any estimate of expansion cost and caseload, however, is subject to considerable uncertainty. For example, while restricted‑scope enrollees generally automatically would shift over to full‑scope coverage once eligible, how many of the individuals who are not currently enrolled in restricted‑scope coverage would choose to enroll in full‑scope coverage once eligible is unclear. In addition, average costs for this caseload could be significantly different than the average costs for current full‑scope enrollees due to differences in their health needs. For example, research on the health of the U.S. and California populations shows that immigrants, including undocumented immigrants, have lower disability rates than other residents. To the extent this is true for the proposed expansion population, their average per‑enrollee costs could be significantly lower than existing full‑scope enrollees. This is because Medi‑Cal enrollees with disabilities tend to have health care costs that are two to ten times higher on a per‑enrollee basis than other enrollees.

Extended Time Frame Relative to Past Expansions Impacts Access to Coverage. As currently structured, this expansion would occur no sooner than a year and a half following its approval (provided it is approved). In comparison, past expansions were implemented within a year of being approved. Adopting a similar implementation time frame as past expansions for all or part of this remaining age group would accelerate implementation and could improve access to health care sooner. Moreover, the extended implementation time frame could result in some young adults losing coverage while waiting for the proposal to be implemented. Currently, the potential number of young adults who could lose full‑scope coverage prior to January 1, 2024 is particularly large because many young adults who otherwise would have aged out of full‑scope Medi‑Cal (upon turning 26 years of age) have been able to keep their benefits as a result of a federal policy that effectively prevented eligibility terminations except in limited circumstances during the COVID‑19 national public health emergency. (For more information on this federal policy and its impacts on the Medi‑Cal caseload, please see our recent publication, The 2022‑23 Budget: Analysis of the Medi‑Cal Budget.) While there is some uncertainty regarding the number of young adults who would lose full‑scope coverage once the public health emergency ends, we estimate that upwards of 40,000 undocumented young adults could lose full‑scope coverage between the end of the public health emergency until they would regain eligibility after January 1, 2024. These lapses could have a negative impact on health outcomes for the affected population and also would create additional administrative workload—first to convert them to restricted‑scope coverage when they lose eligibility upon aging out and then to re‑enroll them in full‑scope coverage once the expansion is implemented.

Administration States That Earlier Implementation Could Create Workload Challenges. The administration has stated that, due to competing workload, implementing the proposed expansion any sooner than January 1, 2024 would be difficult. The competing workload largely is attributed to the following:

Conversion to the California Statewide Automated Welfare System (CalSAWS). Eighteen counties plan to convert to CalSAWS (a statewide system to manage eligibility and enrollment data across various public benefit programs) between October 2022 and October 2023. In addition to this process increasing administrative workload temporarily, updating CalSAWS to reflect changes in Medi‑Cal eligibility policies is challenging, such that carrying out eligibility policy changes while the information technology systems changes are taking place could result in information being inaccurate in one or both systems due to a need to rely on manual processes.

Resumption of Eligibility Redeterminations. In addition, during the national COVID‑19 public health emergency, the federal government effectively prohibits terminating Medi‑Cal coverage for existing beneficiaries except in limited circumstances. After the public health emergency ends, counties will need to complete eligibility redeterminations for the entire Medi‑Cal caseload (which we estimate could be at about 14.9 million enrollees depending on the end date of the public health emergency) and end coverage for any enrollees who are no longer eligible for Medi‑Cal.

Implementation of Full‑Scope Medical Expansion to Undocumented Residents Aged 50 or Older. As was noted previously, undocumented residents who are aged 50 or older will become eligible for full‑scope Medi‑Cal beginning May 1, 2022. Doing an additional expansion within a short time frame potentially could complicate work associated with the 50‑and‑older expansion, as it affects the training of eligibility workers and outreach provided to potential beneficiaries.

We acknowledge that similar to past expansions, implementing this proposal likely would result in a temporary increase in administrative workload, largely for counties due to their key role in Medi‑Cal eligibility administration. While counties would be facing additional workload demands simultaneously, we suggest the Legislature consider alternative strategies for implementation.

Incremental Approach Could Expand Coverage Faster and Partially Reduce Workload Impacts. While we recognize that the workload challenges of an earlier expansion than that proposed by the administration could be impactful, they are not necessarily insurmountable. Notably, the Legislature could take a more incremental approach to the expansion that could reduce, although not fully eliminate, some of the workload challenges noted previously. For example, the Legislature could take steps to prevent lapses in full‑scope coverage for young adults who would age out of coverage prior to January 1, 2024. Two potential approaches would include (1) directing counties to maintain full‑scope coverage for enrollees who would otherwise be moved to restricted‑scope coverage due to their age or (2) expanding coverage to people up to age 30 ahead of the broader January 1, 2024 expansion date. (The latter option would extend eligibility to people who would otherwise lose eligibility due to turning 26 after the start of the national COVID‑19 public health emergency in 2020, when eligibility terminations were suspended and prior to January 1, 2024, when the proposed expansion would be implemented.)

Recommendation

To the extent the Legislature is interested in adopting an accelerated time line for all or part of the population impacted by this proposal, we recommend that the Legislature request that the administration provide information about the feasibility, administrative cost, and caseload impact of adopting an alternative approach to implementation. (The Legislature also might seek similar input from counties due to their key role in Medi‑Cal eligibility administration.) Potential alternatives could, but do not necessarily need to, include the options raised above to prevent coverage lapses for undocumented residents who are currently enrolled in full‑scope Medi‑Cal but, due to their age, would lose their coverage while waiting for the proposal to be implemented.

Reduce Medi‑Cal Premiums to Zero Cost

Background

Certain Medi‑Cal Enrollees Must Pay Premiums to Be Enrolled in Medi‑Cal. The vast majority of California’s Medi‑Cal enrollees do not pay premiums. However, state residents with certain characteristics and who have incomes above standard Medicaid thresholds may enroll in Medi‑Cal provided they pay premiums. Figure 4 provides more details on the specific groups of state residents who may enroll in Medi‑Cal with premiums, as well as the amount of premiums they pay. Populations that potentially can enroll in Medi‑Cal with premiums despite otherwise not being income‑eligible include children, pregnant women, and persons with disabilities who are employed.

Figure 4

Medi‑Cal Populations Currently Required to Pay Premiums

Demographic Group

FPL Income Rangea

Estimated Caseload

Monthly Premium

Children ages 1 through 18

161% ‑ 266%

504,000

$13 per child, $39 family max

Children ages 0 through 1

267 ‑ 322

2,000

$13 per child, $39 family max

Children 0 through 18 in select countiesb

267 ‑ 322

9,000

$21 per child, $63 family max

Pregnant or postpartum persons

214 ‑ 322

6,000

1.5 percent of income

Working persons with disabilities

139 ‑ 250

15,000

From $20 to $250 per personc

Reduce All Medi‑Cal Premiums to $0. The Governor proposes to reduce all Medi‑Cal premiums to $0 beginning July 2022. The administration estimates that this would cost $18.9 million General Fund ($53.2 million total funds) in 2022‑23, increasing to $31 million General Fund ($89 million total funds) ongoing.

Assessment

Proposal Would Help Improve Affordability and Access. Reducing premiums to zero would help reduce health care costs for the impacted populations who are relatively low income. It also could help to improve coverage among people who are otherwise qualified for these programs but are not enrolled. First, research shows that premium costs deter enrollment—including in similar programs. As such, reducing premiums to $0 should remove any deterrent effect of the current premiums. Second, because failure to pay premiums can result in people being disenrolled from Medi‑Cal, this proposal likely would result in fewer people losing Medi‑Cal coverage.

Fiscal Impact of Potential Increase in Caseload Is Lacking in Administration’s Cost Estimate. The administration has stated that it expects any caseload impacts of the premium reductions would be minor and difficult to predict. As such, they do not estimate a caseload impact from the proposed policy change, nor any associated costs. However, because the proposal would remove the deterrent effect of premiums and reduce the number of people who are disenrolled from Medi‑Cal for not paying premiums, we think that there is a high likelihood there would be at least some impact on caseload. While there is considerable uncertainty about the caseload impact and corresponding costs, we think these costs could be in the tens of millions of dollars General Fund.

Unclear How Policy Would Impact Potential Enrollees Who Owe Backpay. At the time of this analysis, how the proposal would impact potential enrollees who owe past‑due premiums is unclear. If left unaddressed, these enrollees would still need to pay the past‑due premiums before they can re‑enroll in Medi‑Cal, even after premiums have been eliminated.

Recommendation

Request Additional Information Before Approving. Due to the potential impact this could have on improving access and affordability for low‑income Californians, we agree with the policy basis for the proposal. However, before approval, we recommend that the Legislature ask the administration why their assumption of no caseload impact is reasonable and how past‑due premiums would be handled. This information will be key to fully understanding both the budget and policy implications of the proposal—and to determining whether the proposal should be approved as is or with modifications to the cost estimates and/or trailer bill language.

Establish Office of Health Care Affordability

In this section, we (1) provide additional background on how overall health care costs have grown in California over time, (2) give context to efforts in recent years to establish the state Office of Health Care Affordability to control rising overall health care costs, (3) describe the Governor’s proposal to establish—through budget‑related legislation and an associated re‑appropriation of funds—an Office of Health Care Affordability housed within the Department of Health Care Access and Information (HCAI) to control health care cost growth, and (4) provide issues for legislative consideration regarding this proposal.

Background

Health Care Costs in California Generally Have Grown Significantly Over Time. Increases in both health care prices and utilization of health care services generally have led to higher health care costs over time. (For example, there was substantial growth in health insurance premiums for employer‑sponsored health plans of nearly 80 percent—or roughly 4.7 percent per year—between 2000 and 2017.) For comparison, inflation in the price of nonmedical services grew by roughly 4 percent per year in both Greater Los Angeles and the Bay Area over the same time period.

To some extent, health care—like other parts of the service sector—is structurally predisposed to greater growth in costs. (For example, the inflation in nonmedical service sectors discussed above is still higher than overall inflation over the same time period.) Nevertheless, growth in health care costs is attributed at least in part to distinctive market conditions that particularly impact health care prices such as reduced competition among health care payers and providers due to mergers and acquisitions in the health care sector. As discussed earlier, these increased health care costs have led to Californians foregoing or deferring needed medical care.

Some States Have Created Entities to Control Health Care Costs. One approach to controlling health care cost growth is to establish a regulatory body or independent entity tasked with implementing a strategy for doing so. To achieve the goal of controlling health care cost growth, these regulatory bodies or independent entities could perform several functions, such as (1) collecting detailed financial information from a comprehensive set of health care payers and providers, (2) providing incentives to encourage health care payment models based on the quality of care provided rather than strictly costs, (3) setting targets for health care cost growth, and (4) levying penalties on health care entities that do not meet health care cost growth targets. Some states—including Massachusetts, Maryland, Rhode Island, and Oregon—have created entities that perform some or all of the cost control functions described above. The efforts implemented in Maryland, Rhode Island, and Oregon are relatively new. Accordingly, a comprehensive picture of how effective they have been at controlling health care costs in these states is not available. However, the independent entity in Massachusetts has been in place since 2012. In the decade since, Massachusetts stayed within its state health care cost growth targets for the first several years of implementation. However, it has exceeded its growth targets in two consecutive years since then.

Prior Efforts to Create Office of Health Care Affordability Were Either Delayed or Stalled. The Governor first proposed the establishment of an Office of Health Care Affordability—to be housed in the California Health and Human Services Agency (CalHHS)—in the January 2020 budget. This proposal subsequently was withdrawn after the onset of the COVID‑19 pandemic. However, the 2020‑21 budget package included budget‑related legislation authorizing the establishment of the Health Care Data Payments Program (HPD). The HPD—currently housed within HCAI—is intended to function as a large research database derived from individual health care payment transactions. When it comes online in 2023, the database will be used to analyze total health care expenditures statewide to identify key cost drivers and inform recommendations on how to mitigate rising costs. The HPD is envisioned as a key component of the Office of Health Care Affordability. The Governor’s January 2021 budget re‑proposed the establishment of the Office of Health Care Affordability, to be housed instead within the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (later reorganized and reconstituted into HCAI). In addition to the Governor’s January 2021 proposal, there was (and remains) a legislative proposal to establish this office being considered in the policy process. While no budget‑related or policy legislation has been enacted to establish the office, the 2021‑22 budget did include an appropriation of $30 million one‑time General Fund to establish the office.

Proposal

Establish Office of Health Care Affordability Through Budget‑Related Legislation. The Governor re‑proposes establishing the Office of Health Care Affordability within HCAI (through the enactment of budget trailer bill legislation). To fulfill its goal of controlling statewide health care costs, the office broadly is intended to increase health care price and quality transparency, develop specific strategies and cost targets for different health care sectors, and impose financial consequences on health care entities that fail to meet these targets. The office would rely heavily on data collected by the HPD to analyze key trends in health care costs to identify underlying causes for health care cost growth (including by reviewing mergers and acquisitions in the health care sector). It also would publicly report total health care spending and factors contributing to health care cost growth, and publish an annual report and conduct public hearings about its findings. In addition, the office broadly would encourage the adoption of health care payment models based on the quality of care provided, as well as monitor the effects of health care cost targets on the health care workforce.

Within the office, the Governor also proposes to establish a Health Care Affordability Board composed of eight members, as follows:

Four members appointed by the Governor and confirmed by the Senate.

One member appointed by the Senate Committee on Rules.

One member appointed by the Speaker of the Assembly.

The CalHHS Secretary or their designee.

The Chief Health Director (or their deputy) of the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (as a nonvoting member).

The proposed board would be charged with key implementation decisions for the office. For example, it would be tasked with approval of the office’s health care cost targets.

Proposed Statutory Language Includes Several Revisions to Prior‑Year Proposal. The Governor’s proposed statutory language to implement the Office of Health Care Affordability includes several revisions compared to the administration’s proposal last year. These revisions include, for example, (1) changes to the size of the internal board (from 11 members in last year’s proposal to 8 members in the current proposal), (2) the addition of authority for the affordability board—rather than the HCAI director—to approve health care cost targets, (3) the addition of certain conditions under which cost targets could be adjusted for health care entities that demonstrate substantial growth in labor costs, (4) updates to financial information required to be collected (to include nonclaims based payments), (5) additions of exemptions for provider groups of certain sizes from the office’s requirements, and (6) modifications to the type of financial statements that would be accepted by the office (to include unaudited statements).

Re‑Appropriate $30 Million General Fund One Time for Establishment of Office. The Governor proposes to re‑appropriate the $30 million General Fund one time to establish the Office of Health Care Affordability provided in the 2021‑22 budget. This amount is intended to fund the first two years of implementation of the office. The 2021‑22 budget assumed that the General Fund eventually would be reimbursed for this cost by the California Health Data and Planning Fund, which is supported by fee revenues collected from health care facilities. This special fund is intended to support the ongoing costs of the office.

Legislative Proposal to Establish Office Will Be Revised to Mirror Governor’s Proposal. As discussed earlier, there also is a legislative proposal to establish an Office of Health Care Affordability currently being considered in tandem with the Governor’s proposal. We understand that it is the author’s intent is to modify this proposal to mirror the Governor’s proposal, so this will be the single proposal for legislative consideration.

Assessment

In Concept, Creating the Proposed Office a Reasonable Yet Ambitious Step Toward Controlling Health Care Cost Growth Statewide… Establishing an Office of Health Care Affordability—tasked with collecting comprehensive financial information from across the health care sector, resourced with the internal expertise necessary to analyze the data it collects, and empowered to enforce targets for health care cost growth—would be a reasonable step for the state to take in an effort to control health care costs. However, this proposal also is quite ambitious. Due to its geographic size, population, and regional diversity, California’s health care system—and its total health care spending—is much larger and more complex than those of the other states that have attempted to establish independent entities or regulatory bodies to control health care costs. Accordingly, carrying out the office’s core functions may be more challenging than it has been in other states. In addition, although other states—in particular Massachusetts—have established similar models to control health care costs, these efforts generally do not have a clear and consistent track record of success. To some extent, this proposed office will need to develop its own best practices to ensure that health care cost growth remains within the specified targets.

…But Continued Monitoring of Implementation Necessary to Ensure Office Achieves Goals. In light of the considerations we raise above, continued monitoring of the implementation of the Office of Health Care Affordability would be necessary to ensure it is successful at controlling health care costs statewide. This would allow the state to identify areas where adjustments to the office—such as in its staffing levels and regulatory authority—would increase the likelihood that it would achieve its intended goals.

Issues for Legislative Consideration

Consider Where Further Adjustments to Proposal Are Needed to Address Legislative Priorities. As discussed earlier, the Governor’s proposal includes a number of changes relative to last year’s proposal. The Legislature may wish to ask the administration to explain the rationale for these changes and then consider the extent to which it agrees with the changes to the proposed office. If it does not agree with all or some of the revisions relative to last year’s proposal, the Legislature may wish to make its own adjustments to the proposed statutory language to establish the office.

Consider Putting a Regular Process in Place to Ensure Legislative Oversight of Implementation Given continued monitoring of implementation for this office is warranted (if enacted), the Legislature may wish to consider putting a process in place to ensure legislative oversight of its implementation and ongoing efforts. The proposed statutory language to establish the office broadly requires that the Office of Health Care Affordability be responsive to legislative requests for information and testimony. Given the ambitious nature of this proposal, the Legislature may wish to consider creating a more defined process to carry out its oversight functions. This could include requiring regular check‑ins, such as on a biannual basis, with the administration to gain information on how implementation is going.

Reduce the Cost of Insulin Through State Partnership

Background

Addressing High Pharmaceutical Costs Has Been a Key Priority of the Governor and Legislature. High pharmaceutical costs have been identified as a concern of both the Legislature and Governor. These costs have been attributed to a variety of factors, including a lack of competition within the pharmaceutical industry. The state has taken a number of efforts to address prescription drug costs. For example, the Governor signed executive orders in 2019 directing various actions to address high pharmaceutical costs. These orders included directing the state to (1) expand a statewide bulk purchasing program to include nonstate entities such as local governments and (2) transition the Medi‑Cal pharmacy services benefit from managed care to fee for service (a change now known as “Medi‑Cal Rx”) in order to achieve state savings and standardize the Medi‑Cal pharmacy services benefit. In 2020, the Legislature passed Chapter 207 of 2020 (SB 852, Pan) which authorized efforts to expand the state’s role in securing lower cost drugs for Californians. Specifically, SB 852 directed CalHHS to enter into partnerships resulting in the production or distribution of generic prescription drugs with the intent of making these drugs widely available to the public and private purchasers.

SB 852 Includes Criteria to Ensure Partnerships Are Viable and Able to Achieve Established Goals. Senate Bill 852 requires that before a partnership is entered into, CalHHS must (1) only enter into a partnership to produce a generic prescription drug at a price that results in savings, targets failures in the market for generic drugs, and improves patient access to affordable medications, and (2) examine the extent to which legal, market, policy, and regulatory factors could impact the viability of the proposed partnership.

In addition, SB 852 requires reporting by the administration regarding the potential impacts and feasibility of a partnership. First, by July 1, 2022, SB 852 requires the administration to report on its findings related to the status of drugs being targeted and how state efforts could impact competition, access to drugs, and their costs. Second, by July 1, 2023, SB 852 requires the administration to produce a report on the feasibility of directly manufacturing and selling generic drugs.

Governor’s Forthcoming Proposal

The Governor has announced a forthcoming proposal for a potential partnership to manufacture insulin. The stated intent is to increase the availability of insulin that is priced at a fraction of current market prices. According to the administration, more detail on this proposal will be released in the spring.

Assessment

Insulin Could Be an Appropriate Focus for a Partnership… Insulin costs have increased substantially over the last two decades. Currently, even with insurance, patients can end up paying thousands of dollars in annual out‑of‑pocket costs for insulin. In addition, the production of insulin is heavily dominated by a handful of companies. Due to the high prices and market consolidation, a state partnership to produce and distribute generic insulin has the potential to be an appropriate focus under SB 852. Moreover, SB 852 explicitly requires that at least one partnership the state enters into shall be for the production of insulin, provided that there is a viable pathway to manufacturing a more affordable form of insulin and that the partnership meets the SB 852 criteria previously discussed.

… But Uncertainty Remains Regarding Whether Proposal Would Meet SB 852 Criteria for Viability and Other Factors. While the proposed partnership has the potential to be an appropriate focus, whether the partnership would meet the criteria under SB 852 is unclear. As noted earlier, SB 852 requires the administration to examine legal, market, policy, and regulatory factors that could impact the viability of the proposed partnership. While the administration notes that these efforts are underway, they have not yet been completed. In addition, if the state ultimately would be able to produce generic insulin at a price that results in savings and improves patient access to affordable medication as required by SB 852 remains unclear.

Reporting Required by SB 852 Likely Critical to Assessing Feasibility of the Proposal. As noted earlier, SB 852 requires the administration to report on both (1) its findings related to the status of drugs being targeted and how state efforts could impact competition, access to drugs, and their costs, and (2) the feasibility of directly manufacturing and selling generic drugs. This reporting (which is due later in 2022 and 2023) likely would be critical to assessing the feasibility of the proposal. As such, why the administration appears to be moving forward with this proposal ahead of this reporting is unclear.

Recommendation

Withhold Any Necessary Approvals Until Additional Information Provided. While we acknowledge that a partnership to produce and distribute insulin has the potential to be an appropriate partnership under SB 852, we recommend that the Legislature hold off on approving the proposal until information is provided to ensure that the proposed partnership meets the criteria included in the legislation. This information should include (1) an evaluation of legal, market, policy, and regulatory factors that could impact the viability of the partnership, and (2) whether the state would be able to produce generic insulin at a price that results in savings and improves patient access to affordable medication. The Legislature also might want to consider awaiting the legislative evaluation of the reporting required by SB 852 before providing the authority to the administration to enter into any partnerships.

During last year’s budget process, the Legislature directed Covered California to develop options, for consideration during the 2022‑23 budget process, to improve affordability for Californians who have purchased health insurance through Covered California and make up to 400 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL). On January 10, 2022, Covered California released a report with affordability options for consideration by the administration and Legislature. At this time, there are no budget proposals before the Legislature regarding these options. The administration has stated that it is still reviewing the options. As such, if the administration decides to propose affordability options for Covered California, the proposal would be later in the budget cycle. Regardless of whether the administration ultimately comes forward with a proposal, the Legislature could consider the options in the Covered California report and decide whether to take action regarding the affordability of plans offered through Covered California.

Background

Federal Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) Substantially Changed Individual Health Insurance Market Landscape. The ACA—most of the provisions of which became effective in 2014—brought about significant changes to the way that health insurance coverage is provided in California. This included significant changes within the individual health insurance market. Notably, the ACA provided for the establishment of state health benefit exchanges, such as Covered California. Consumers who shop for coverage on Covered California can choose among health insurance plans organized into standardized metal tiers, including bronze, silver, gold, and platinum. These tiers vary in the amount of monthly premiums they charge and out‑of‑pocket costs they require households to pay, such as annual deductibles and co‑pays for medical visits. Bronze plans have the lowest premiums but have the highest out‑of‑pocket costs. For example, bronze plans feature a large deductible that must be met before many medical services are covered. Silver, gold, and platinum plans require progressively lower out‑of‑pocket costs, but also come with higher premiums.

To improve affordability, the ACA created two types of subsidies that work together to reduce the cost of health insurance for households who purchase coverage through Covered California if they meet certain income‑eligibility criteria and do not otherwise have access to affordable coverage—such as through an employer, Medi‑Cal, Medicare, or another qualifying program. (The federal government currently considers coverage to be affordable if self‑only premium costs [that is, excluding other family members] are no higher than 9.6 percent of household income.)

Advance Premium Tax Credit (APTC). The APTC—as structured under the ACA—offsets the cost of health insurance premiums for households with incomes between 100 percent and 400 percent of the FPL. This tax credit effectively limits a household’s net premium for a silver plan (after accounting for the tax credit) to between 2 percent and 10 percent of annual income. (This percentage increases as income increases.)

Cost‑Sharing Reductions. While the APTC offsets premium costs, cost‑sharing reductions are subsidies that reduce households’ out‑of‑pocket costs such as co‑pays, deductibles, and annual out‑of‑pocket maximums. Under the initial years of the ACA, the federal government provided funding for cost sharing reductions for insurers in Covered California to offer various “enhanced” silver plan options to households with incomes between 100 percent and 250 percent of the FPL. These plans are often referred to by the average percent of a member’s health care costs that the plan pays. For example, on average, a Silver 94 plan pays 94 percent of member health care costs. Plans with higher numbers—which have a lower income threshold for enrollment—are considered more generous because the consumer pays lower out‑of‑pocket costs. In 2017, the federal government stopped providing funding for cost‑sharing reductions but did not remove the requirement for insurers to offer enhanced silver plans that included cost‑sharing reductions. In order to accommodate the increased cost of silver plans, insurers raised premiums for silver plans. (We note that due to the APTC, the federal government ultimately paid for the increased premium costs for consumers making less than 400 percent of the FPL.)

ACA Created Individual Mandate That Was Subsequently Set to Zero. As originally enacted, the ACA imposed a requirement, referred to as the individual mandate, that most individuals obtain specified minimum health insurance coverage or pay a penalty. The individual mandate was intended to discourage people from going without health insurance coverage, particularly younger and healthier individuals who have lower risk of incurring health care costs and who otherwise would be less likely to enroll in coverage. Increased coverage of younger, healthier populations leads to a more balanced insurance risk pool and allows the costs of covering higher‑risk populations to be spread more broadly. This, in turn, reduces the average cost of coverage and helps to offset the increased cost of making individual market coverage more comprehensive under the ACA. However, due to subsequent federal legislation, the penalty for violating the individual mandate has been reduced to zero, effectively eliminating the requirement.

State Introduced Individual Mandate Penalty and Established Three‑Year Premium Subsidy Program. In 2019‑20, the Legislature enacted a state individual mandate penalty as well as a three‑year state premium subsidy program intended to supplement federal subsidies through Covered California. The state’s individual mandate penalty, which was modeled on the federal individual mandate penalty, went into effect in 2020 and is ongoing. The subsidy program was designed as a three‑year program from 2020 through 2022 that would reduce premium costs for most Covered California enrollees—including those making between 400 percent and 600 percent of the FPL who were not eligible for the federal premium subsidies. The state subsidies were structured to limit premium costs to a percentage of income (with the percentage increasing with income) for households making up to 600 percent of the FPL.

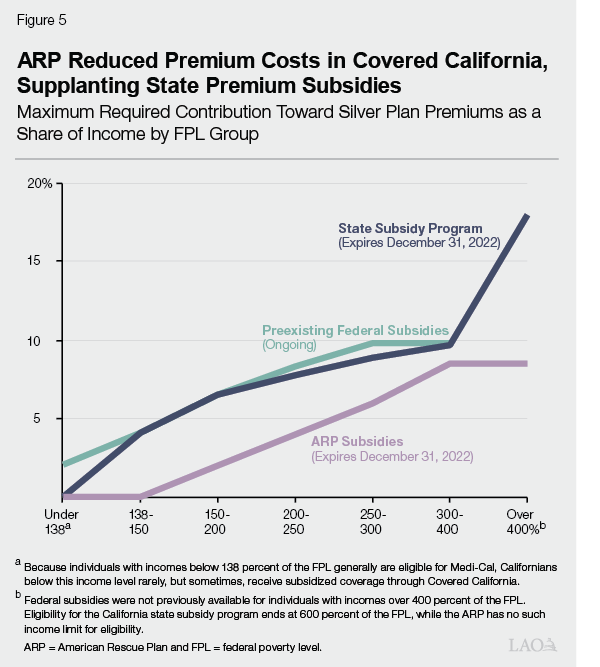

Enhanced Federal Premium Subsidies in Effect Supplanted State Subsidies in 2021 and 2022. The American Rescue Plan (ARP) Act was passed by Congress in 2021 in response to COVID‑19. As part of this act, the level of federal support for premium subsidies for coverage purchased on health benefit exchanges have been temporarily increased for the 2021 and 2022 plan enrollment years. As seen in Figure 5, the increased federal premium subsidies substantially lower the cost of premiums Californians need to pay for plans purchased through Covered California—including for households whose incomes made them ineligible for the preexisting premium subsidies under the ACA. In total, the increased federal support has resulted in about $1.6 billion in reduced premium costs for Californians annually in each of 2021 and 2022.

State Set Aside Funding for Future Affordability Program and Required Report on Affordability Options. The increased federal support effectively supplanted the state premium subsidies because it reduced premium costs as a percent of income below the thresholds established in the state program. This freed up General Fund that otherwise would have gone toward the state premium program. As part of the 2021‑2 budget package, Chapter 143 of 2021 (AB 133, Committee on Budget) set aside $333.4 million of this freed‑up General Fund to support future affordability efforts. Assembly Bill 133 also required Covered California to develop options for reducing out‑of‑pocket costs for enrollees making up to 400 percent of the FPL and to provide these options to the Legislature and Governor for consideration in the 2022‑23 budget process.

Pending Federal Legislation Could Extend ARP Act Premium Subsidies and Provide Additional Cost‑Sharing Reductions. As noted above, the increased federal support through the ARP Act only extends through 2022. However, pending federal legislation (referred to as the Build Back Better Act) would extend the increased federal support through 2025. The legislation also would provide a total of $10 billion nationwide annually between 2023 and 2025 to support new cost‑sharing reductions. (The likelihood of the pending federal legislation—or legislation with similar provisions—ultimately being approved by Congress is highly uncertain at this time.)

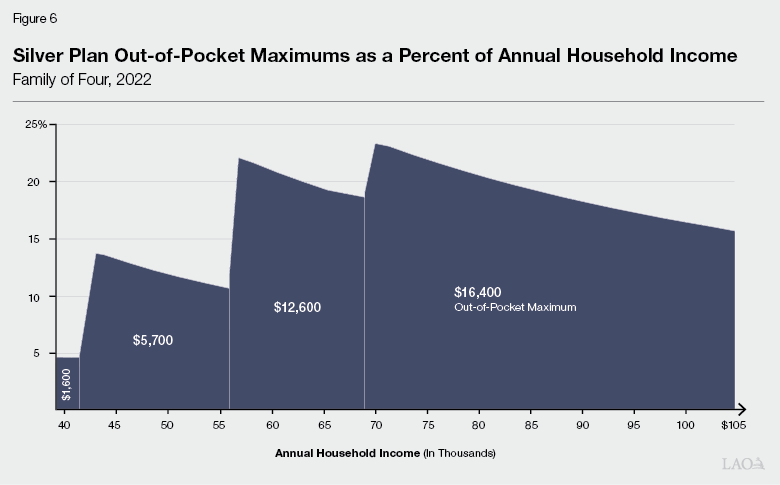

Affordability Remains an Issue for Households With High Out‑of‑Pocket Costs. Even with the federal premium subsidies and the cost‑sharing reductions established through the ACA, affordability remains an issue for both low‑income consumers who are eligible for plans that include the ACA cost‑sharing reductions as well as higher‑income households. As shown in Figure 6, households at various income levels who are enrolled in silver plans potentially can end up paying a high percent of their annual income on health expenditures. For example, a family of four making about $40,000 per year and enrolled in an enhanced Silver 87 plan (with cost‑sharing reductions) could end up paying $5,700 out of pocket (over 14 percent of their income) over the course of a year and potentially within a much shorter period of time. A four‑person household, making roughly $67,000 per year and enrolled in a standard Silver 70 plan (with no cost‑sharing reductions) could end up paying $16,400 (almost 24 percent of their income) in out‑of‑pocket costs over the course of a year.

Recent Report Provides Various Options to Improve Affordability

Report Highlights Various Options to Improve Affordability. On January 10, 2022, Covered California released a report with various options for cost‑sharing reductions to improve affordability for silver plans purchased through Covered California in response to AB 133’s reporting requirement. These options are laid out in more detail in Figure 7, but generally involve eliminating deductibles (which are primarily assessed for inpatient services) and providing at least some portion of enrollees with more “generous” plans than they would otherwise qualify for—which would reduce out‑of‑pocket costs. (The generosity of a plan refers to the percentage of a member’s health care costs that it is assumed to cover.) At this time, the administration has not put forward a proposal regarding these options.

Figure 7

Summary of Options Presented in

Covered California Report

Options

Estimated State

Fiscal Impacta,b

Option 1

Households with incomes above 150 percent up to 600 percent of the FPL would be upgraded to more generous plans.

$475 million to $626 million

All deductibles would be eliminated.

Option 2

Households with incomes above 150 percent up to 400 percent of the FPL would be upgraded to more generous plans.

$463 million to $604 million

All deductibles would be eliminated.

Option 3

Households with incomes above 150 percent up to 400 percent of the FPL would be upgraded from existing plans to plans somewhat less generous than in Option 2.

$386 million to $489 million

All deductibles would be eliminated.

Option 4

Similar to Option 3 but with less generous upgrades for households with incomes above 250 percent up to 300 percent of the FPL.

$362 million to $452 million

All deductibles would be eliminated.

Option 5

Households with incomes above 150 percent up to 250 percent of the FPL would be upgrade to more generous plans.

$278 million to $322 million

All deductibles would be eliminated.

Option 6

No change for households at or below 200 percent of the FPL. Households above 200 percent and up to 400 percent of the FPL would be upgraded to a more generous plan.

$128 million to $189 million

All deductibles would be eliminated.

Option 7

No change for households up to 250 percent of the FPL. Relative to Option 6, somewhat less generous upgrades for households above 250 percent up to 400 percent of the FPL.

$37 million to $55 million

Deductibles would not be eliminated.

Funding Issues Affecting Affordability Options

The section below discusses some issues for legislative consideration regarding potential changes in the amount of federal funding available to improve affordability in Covered California and other potential sources of funding.

Will Federal Support for Premium Subsidies in ARP Act Be Extended? As noted earlier, pending federal legislation potentially would extend the federal support for enhanced premium subsidies provided through the ARP Act through 2025. However, if the enhanced premium subsidies are not extended and the state took no action in response, this would result in a substantial increase in premium costs for households enrolled in Covered California. Covered California noted in its report that if faced with increased premiums, thousands of existing enrollees might choose to drop coverage. In the event the federal premium subsidies under ARP are not extended, the Legislature may wish to consider reestablishing a state premium subsidy program before considering adopting state‑funded cost‑sharing reductions (such as the options provided in the Covered California report) due to the potential adverse impact increased premium costs could have on affordability and thus access to coverage.

Will the Federal Government Provide Funding for Cost‑Sharing Reductions? The pending federal legislation would provide $10 billion in federal funding for additional cost‑sharing reductions. California’s share could potentially exceed $1 billion, although the amount of funding and level of discretion provided to the state remains uncertain. In the event this funding is approved, the state would have considerably more resources to address affordability of plans provided through Covered California. However, the Legislature would need to take into consideration potential federal requirements on how this funding is utilized. In addition, the Legislature will want to take into consideration that even if the pending federal legislation is approved, the federal funding for cost‑sharing reductions would only be provided through 2025.

Beyond Federal Funding, What Other Funding Could Be Used? Aside from the potential for enhanced federal funding, the Legislature could choose to authorize General Fund for the purpose of implementing affordability options in Covered California. For example, the Legislature may wish to spend an amount similar to the estimated revenues from the state’s individual mandate penalty for a state subsidy program. Revenues from the penalty for the 2020 tax year were about $400 million.

Other Issues for Legislative Consideration

Regardless of what sources of funding are used, we suggest the Legislature consider various other issues if it chooses to establish a state cost‑sharing reduction program (such as one of the options provided in the Covered California report). A few issues for consideration are discussed below.

What Specific Affordability Goals Should Be Pursued? If the Legislature decides to establish a cost‑sharing reduction program, determining what specific affordability goals should be pursued will be important. For example, the Legislature could focus on improving affordability for lower‑income households who, despite being eligible for federal cost‑sharing reductions, can still pay a significant portion of their income on health care due to deductibles and out‑of‑pocket maximums. Alternatively, the Legislature could focus on expanding cost‑sharing reductions to households with incomes above 250 percent of the FPL who do not currently qualify for federal cost‑sharing reductions and, as a result, potentially could end paying an even higher percent of their income on health care.

While Covered California’s report is heavily focused on affordability for existing enrollees, in 2023, about 700,000 Californians are projected to be uninsured but eligible for subsidized Covered California plans while an additional 200,000 uninsured Californians would be eligible for unsubsidized Covered California plans. Encouraging these Californians to enroll in Covered California could significantly reduce the number of uninsured Californians. Accordingly, the Legislature might want to focus on affordability options that promote further take‑up of insurance coverage. While Covered California provides detailed information about the impacts of its options on affordability for different income groups, however, the report does not consider potential impacts the options would have on enrollment.

What Out‑of‑Pocket Costs Should a State Cost‑Sharing Reduction Program Address? The Legislature also may wish to consider what type of out‑of‑pocket costs should be focused on by such a cost‑sharing reduction program. The majority of the options put forward by Covered California include eliminating deductibles and providing consumers with more generous plans that reduce various out‑of‑pocket costs. Only one option would provide more generous plans but would not eliminate deductibles. The options that eliminate deductibles are considerably more expensive. However, the Legislature might want to consider these options for two reasons. First, inpatient deductibles are substantially higher than other forms of out‑of‑pocket costs. While many consumers do not utilize these services, those who do are much more likely to reach their out‑of‑pocket maximums. Second, deductibles can have a deterrent effect on consumers. Notably, if consumers are confused about when such deductibles apply, they may avoid enrolling in plans or receiving health care, including services that are not subject to inpatient deductibles.

Would the Cost‑Sharing Reduction Program Be Limited Term or Ongoing? The Legislature also may want to consider what duration a state‑funded cost‑sharing reduction program should be. A one‑year or limited‑term program would reduce the state’s fiscal exposure and potentially avoid exceeding the $333.4 million that was set aside in 2021‑22. In addition, if the pending federal legislation to provide funding for cost sharing is approved, the associated federal funding would expire in 2025. As such, a limited‑term state program could be better aligned with that funding source and later restructured or eliminated when the federal funding goes away. However, there are trade‑offs of a limited‑term program. For example, consumers may be less willing or able to make any necessary changes to their health plans in order to benefit from a program that has a short duration.

Legislative Next Steps

While no specific proposal has been put forward by the administration, action would need to be taken within the 2022‑23 budget process in order to take effect in Covered California’s 2023 plan year. We recommend that the Legislature take into consideration the issues raised above when considering what actions to take—either in reviewing any potential proposal from the administration that might be released at May Revision or in developing direction to the administration on what options to implement.

The Governor’s proposals—if approved by the Legislature—would improve significantly access to comprehensive health coverage and to some extent improve affordability. In addition, potential actions taken to improve affordability in Covered California would reduce health costs for impacted households. However, various issues regarding access to comprehensive health coverage and affordability of health care would remain even if the above actions were all taken. We provide a few notable examples of these issues below.

Examples of Issues Impacting Access to Comprehensive Coverage. These access issues include:

Access to Covered California for Undocumented Residents. While the Governor’s proposal would expand Medi‑Cal coverage to all income‑eligible undocumented residents, access to coverage would remain an issue for undocumented residents who are not income‑eligible for Medi‑Cal. While there is considerable uncertainty about the size of this population, we estimate there likely are 300,000 people affected. Due to federal requirements, such individuals are excluded from purchasing coverage through Covered California. However, the state potentially could seek a federal waiver to allow such individuals to purchase coverage. Even with a waiver, however, costs of plans purchased likely would either need to be unsubsidized or the state would need to pay for any subsidies that would otherwise be funded by the federal government.

Reducing Number of People Eligible for but Not Enrolled in Medi‑Cal. Roughly 500,000 people are eligible for but not enrolled in Medi‑Cal, although it is not necessarily the same 500,000 people at a given time due to an issue known as “churning.” Churning refers to when individuals lose eligibility for Medi‑Cal on a temporary basis before resuming coverage, often within a year. The lapses in coverage due to churning can result in issues with continuity of care. Reasons for churning can be due to short‑term changes in circumstances such as temporary increases in income, but it also can be due to administrative issues such as failure to respond to Medi‑Cal eligibility redetermination notices within a given amount of time. The Legislature could consider asking the Department of Health Care Services for other options to streamline the eligibility redetermination process from a beneficiary perspective for the purpose of reducing churn. Alternatively, the Legislature could consider adopting a continuous coverage policy to allow enrollees to remain on Medi‑Cal for a period of time, such as a year, without being subject to an eligibility redetermination (this would require a federal waiver).

Examples of Issues Impacting Affordability. These affordability issues include:

Addressing Share of Costs in Medi‑Cal. Certain individuals who would otherwise not be eligible for Medi‑Cal due to their income are allowed to enroll in the program but must pay a share of cost before enrolling in Medi‑Cal. Most share‑of‑cost Medi‑Cal recipients are enrolled in the medically needy program which is largely comprised of persons with disabilities as well as people who are aged or blind. In contrast to the payment of premiums, individuals who pay a share of cost must meet a monthly deductible before Medi‑Cal begins to pay for health care. The amount of deductible that must be paid each month is calculated as the enrollee’s net nonexempt income minus a basic amount determined to be necessary for cost of living, known as the “maintenance need level.” California has not applied cost‑of‑living adjustments to the calculation of the maintenance need level since 1989, even though federal law allows for such adjustments, resulting in a current maintenance need level of only $600. Introducing inflation adjustments into the program could help mitigate increasing affordability challenges for its enrollees.

Fixing the “Family Glitch.” Under the ACA, households that have access to affordable health insurance through other sources such as an employer are ineligible for federally subsidized health plans through exchanges such as Covered California. Under the ACA, households are considered to have access to affordable insurance if at least one member of the household has access to health insurance in which the cost of self‑only coverage is less than a certain percent of household income (currently 9.66 percent). The definition does not consider the cost of coverage for other household members and accordingly has become known as the family glitch because of its potentially adverse impact on families being able to access affordable coverage through the health benefit exchanges. In some circumstances, such as if an employer contributes little to nothing for the coverage of spouses and dependents, households may find it cost‑prohibitive to either add other family members to an employer‑sponsored plan or purchase nonsubsidized coverage through Covered California. While this issue could be addressed through a change in federal legislation, Minnesota recently passed legislation to address the family glitch at the state level. (However, we note that Minnesota’s equivalent to Covered California is structured very differently—and as such, attempting to fix the family glitch in California could require a different approach and be more complicated.)

Reducing Pharmaceutical Costs. This publication discusses the Governor’s proposal to address high insulin costs. Even if that proposal is approved and implemented successfully, high pharmaceutical costs likely will remain a challenge—even after considering he state’s other efforts to reduce such costs. Attempting to address this issue could require additional market interventions—such as attempting to increase competition, consolidating the purchase of pharmaceuticals to a greater extent than today to increase bargaining power, or passing legislation to regulate costs. However, the feasibility of any such intervention is uncertain and could lead to unintended consequences, such as reduced availability if manufacturers choose to reduce the availability of their drugs to Californians due these state interventions.

To the extent the Legislature would like to further the goals of improving access and affordability, it could consider looking into ways to address the issues identified above. This could include asking the administration during budget deliberations about its plans, if any, to address the issues identified, as well as about the feasibility of options to address them. We recognize that options to address some of these remaining access and affordability issues may be costly and complicated and come with significant trade‑offs that warrant serious consideration before proceeding.