Some Starbucks workers forgo paychecks to access IVF treatments – NBC News

Leah Russell felt a surge of hope when she spotted Starbucks on a list of employers that offer fertility benefits in the summer of 2019. She and her husband, Stephen, were desperate to start the family they had been dreaming of since they started dating a decade ago. The couple had recently learned they would need to pay $30,000 for another round of in vitro fertilization, or IVF, treatment after two rounds failed to result in a pregnancy.

“The price tag was just more than we could have ever imagined paying,” said Russell, 28.

Russell said she and her husband had already been rejected by three banks for a loan to cover the additional cost of IVF, the only thing their doctor said might help them conceive. Nebraska, where they live, is one of dozens of states that don’t require insurers to offer coverage for fertility treatments, meaning Stephen and Leah would be on their own to pay for medical help.

Most of the companies in Nebraska that choose to offer fertility coverage are two-hour drives away from the Russells’ home in South Sioux City. Starbucks was one of the only opportunities nearby, which covers up to $10,000 in fertility drugs and $25,000 in fertility treatments for its workers.

“This was my one and only shot, and I’m so grateful that it existed,” Russell said.

Leah and Stephen Russell in September on the ninth anniversary of their first date.Leah Russell

Starbucks, which faces a national labor organizing campaign, has long been known among people struggling with infertility as one of the only major U.S. employers to offer coverage for procedures like IVF to part-time workers. Word about Starbucks’ benefits has spread widely online in recent years. A Facebook group for people who are interested in or already using the perk to start families has more than 8,400 members. On TikTok, videos under the hashtag #StarbucksIVFbaby have amassed over 8.8 million views. The benefits have drawn people across the country to join the company as baristas, like Russell.

But for hourly workers, taking advantage of what Starbucks calls its “world-class” benefits package, including benefits like fertility care, can come with a catch. Six current and former Starbucks employees who joined the company to receive IVF treatment said the premiums for the insurance plans they chose either almost or completely exceeded their paychecks. In some cases, the employees, who worked 20 to 35 hours a week, even accumulated debt with Starbucks. To make ends meet, they said, they relied on their partners’ incomes or worked second jobs.

Experts say that illustrates how skyrocketing health care costs have reached crushing levels for Americans, particularly low-wage workers. A job that pays $15 an hour can rarely offset the price of an expensive procedure like IVF, which can total at least $12,000 per cycle. That’s true even with insurance at a company like Starbucks, which often touts its “innovative benefits.”

“Our health insurance system, which is primarily tied to employment, is not financed in a way that’s progressive,” said Laurel Lucia, the director of the health care program at the University of California, Berkeley, Labor Center. “Low-wage workers who get coverage through their jobs pay a much higher percentage of their income than middle- and higher-income workers.”

It can be nearly impossible for people in service positions at companies like Starbucks to cover medical costs and other expenses at the same time, said Nicole Mason, the president and CEO of the nonprofit Institute for Women’s Policy Research. She argued that the broader issue is that the U.S. health care system doesn’t treat infertility treatment as a medical necessity.

“This benefit, again, might appear very attractive, especially if women are having trouble in terms of fertility,” Mason said. “But because of the way the plans were structured, it makes it pretty much out of reach for families, especially for workers who are working less than full time.”

Rising costs for health care and other living expenses have helped fuel labor organizing efforts at companies like Starbucks. In recent months, employees at seven of the coffee maker’s roughly 9,000 U.S. stores have formed unions, and workers at more than 100 others have filed to hold elections to join one. The employees are asking for higher pay, more consistent scheduling and other improvements.

“We are the first to say how great some of the benefits at Starbucks are. From tuition assistance to health care coverage, we appreciate the benefits Starbucks offers to partners,” the official Twitter account for unionizing Starbucks workers tweeted last April. “This doesn’t mean things couldn’t be better.”

Starbucks has pushed back by creating a website where it argues that unions aren’t necessary at the company, in part because its workers already have what it calls a “leading” benefits package. “These continuously evolving and innovative benefits and perks come from partner feedback and conversations—the power of our direct relationship,” it reads.

In November, Howard Schultz, who returned this month as Starbucks’ interim CEO, made a similar argument in front of a room of unionizing employees in Buffalo, New York, where he highlighted the many “expensive” benefits Starbucks has offered.

“Who forced us to do it? Who pushed us to do it?” he asked. “No one.”

Starbucks workers who have used the company’s fertility benefits have mixed perspectives on unionizing. Some workers who spoke to NBC News defended the company, saying it was providing one of the better options available within a broken health care system. They said they were grateful it gave them the opportunity to potentially have a child. But they wished it didn’t mean they would need to forgo a paycheck.

“I get a lot of feedback on TikTok from people that live in other countries with universal health care or socialized health care, and they are just absolutely shocked at the prospect of finding a job, in addition to your full-time work, that will pay for a medical treatment that you need,” said Autumn Lucy, 33, who owns a small business in Michigan. She joined a Starbucks last year in the hope of receiving fertility treatment. “That is absurd to them, and it’s absurd to me,” she said.

Bailey Adkins, a spokesperson for Starbucks, said many people come to the coffee maker because of its benefits package. She said Starbucks offers a variety of health insurance plans workers can choose from, all of which offer fertility coverage. The majority of employees, she said, choose the mid-tier “silver” option, which typically costs $42 a paycheck for a single person and has a $1,000 deductible. She noted that Starbucks has announced several pay increases over the last few years, the most recent of which brought the average wage for hourly workers to $17.

Starbucks ultimately isn’t required to make its benefits any more affordable than it has already, said Matthew Rae, the associate director of the Health Care Marketplace Program at the nonprofit Kaiser Family Foundation. “Most employers have no obligation to cover any particular benefits,” he said. “This is really just what they decide to cover.”

Workers United, an affiliate of the Service Employees International Union that is representing Starbucks employees, didn’t comment in time for publication.

Rare perks

Russell started working part time around 20 hours a week at Starbucks in 2019 and earned $10.30 an hour. After three full months of work, she was eligible to sign up for insurance benefits. Like a number of Starbucks workers seeking fertility treatments, she calculated that it made the most financial sense to choose one of the “platinum” plans with a high monthly premium but no out-of-pocket deductible. It cost more each paycheck than she said she earned in wages.

The amount her earnings didn’t cover was put into an interest-free arrears account that she will be required to pay back if she ever chooses to work at Starbucks again, she said. The couple relied on Stephen’s $60,000 salary as an electrician to cover living expenses and pay down their pre-existing medical debt.

Russell is one of an increasing number of people in the U.S. who have sought out fertility care. As more women delay motherhood until their late 20s or 30s, the use of fertility treatments like IVF has risen sharply over the past decade, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The surgical procedure involves retrieving eggs and fertilizing them with sperm in a lab before transferring the embryos to a person’s uterus.

Leah and Stephen Russell at the Heartland Center for Reproductive Medicine in Omaha, Neb., on Dec. 14, about 15 minutes before a successful embryo transfer.Leah Russell

Leah and Stephen Russell at the Heartland Center for Reproductive Medicine in Omaha, Neb., on Dec. 14, about 15 minutes before a successful embryo transfer.Leah Russell

For many families, IVF is still unaffordable. “A lot of patients come to me, and unfortunately cost is a barrier,” said the president of the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology, Dr. Timothy Hickman, a reproductive endocrinologist in Houston.

The benefits Starbucks offers are uncommon. Just 42 percent of companies with 20,000 or more employees offered IVF benefits in 2020, according to a survey by the human resources consulting firm Mercer, while only 27 percent of companies with fewer than 500 employees offered the perk.

Some retailers, like CVS and TJX Cos., which operates stores like Marshalls and TJ Maxx, offer IVF treatment benefits to hourly employees, but only those who work full time. Starbucks is one of the few companies that offers the perk to part-time staffers.

Davina Fankhauser, a co-founder and the executive director of Fertility Within Reach, a nonprofit organization that advocates for better access to fertility care, said the way benefits plans are often structured can inadvertently create inequalities. Companies typically set a dollar amount they are willing to cover, which doesn’t account for the fact that the cost of treatments varies widely in different parts of the country.

The laws addressing fertility coverage also vary. Seventeen states have passed regulations that require insurers to either cover or offer coverage for infertility diagnosis and treatment. But most states don’t have any rules. Lucy, the small-business owner in Michigan, got a job at Starbucks after she realized that none of the available plans in her state’s health care marketplace covered IVF.

Union drives

The union drive at Starbucks has brought the company’s business practices into the national spotlight, leading to a number of high-profile disputes with its employees. The National Labor Relations Board, or NLRB, filed a complaint this month accusing Starbucks of retaliating against two workers who were trying to unionize a store in Arizona.

Reggie Borges, a spokesperson for Starbucks, said the company was enforcing standards with the workers it has always held. “We will continue enforcing our policies consistently for all partners, and we will follow the NLRB’s process to resolve this complaint,” he said.

The Starbucks workers who spoke to NBC News varied widely in their opinions about their jobs and the possibility of joining a union. “Starbucks offers all these benefits already,” said Victoria Leigh DePonceau, a part-time Starbucks worker in Manchester, Colorado, who joined the company last fall for its fertility coverage. “So I personally don’t want to pay union dues in a company that I feel is already supporting me.”

Some workers acknowledged that their careers at Starbucks might not be the norm. “I don’t think my experience is representative of most Starbucks employees,” Lucy said. “And if they are not earning a wage that they feel is livable, then I think everyone needs to come to the table and have a discussion.”

Russell said low pay was a recurring issue. She said she received glowing reviews at the company and was promoted to shift leader, which came with a 25 percent pay bump. But both times she requested a raise after her promotion, she said, she was denied. By the time Russell left Starbucks in December, she was earning about $15, the minimum wage goal the company set to reach for all employees by this summer.

Russell said that when she asked her managers why she was denied a raise, they told her it was because the company already offered considerable benefits in addition to hourly wages. “We value it,” she said. “But we also deserve to be able to live on the pay, and that’s something that they just won’t budge on.”

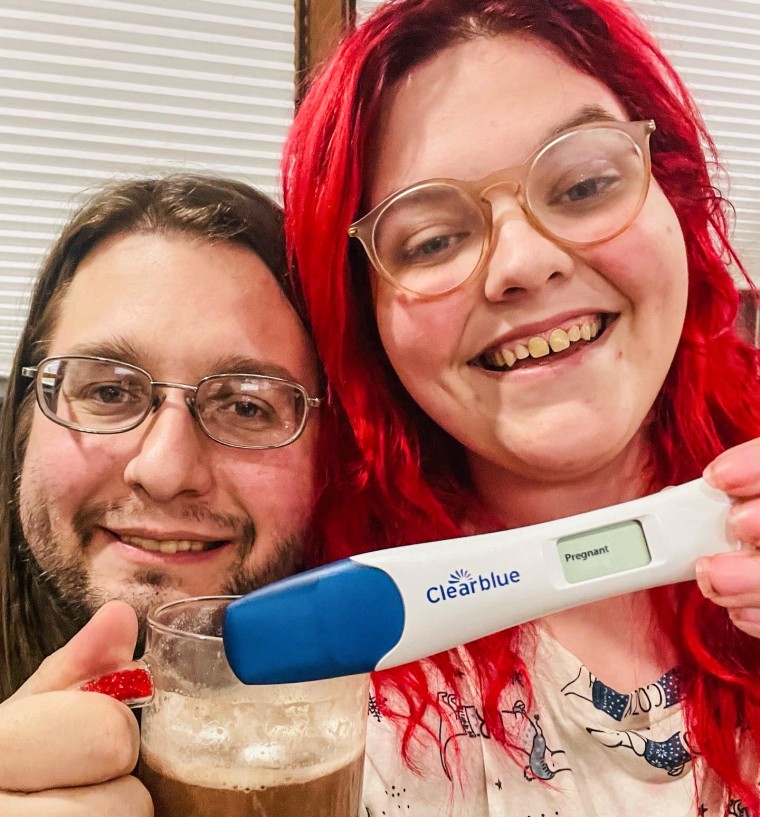

Leah and Stephen Russell celebrate their positive pregnancy test on Dec. 20, days before they were able to share the news with their families.Leah Russell

Leah and Stephen Russell celebrate their positive pregnancy test on Dec. 20, days before they were able to share the news with their families.Leah Russell

Adkins, the Starbucks spokeswoman, said the company generally doesn’t limit wage increases because of benefit offerings.

Russell is in her second trimester as some Starbucks workers consider whether to unionize. She and her husband recently had an ultrasound test and counted all five fingers on one of the baby’s hands.

Starbucks’ fertility coverage gave the couple the ability to try cutting-edge medical treatments and expensive medicines, and it covered one of Stephen’s operations, Russell said. Their out-of-pocket expenses totaled about $3,600. Without the coverage, she estimates, it would have cost $50,000.

Russell left Starbucks in December, after her fertility clinic referred her to an obstetrician-gynecologist who will oversee the rest of her pregnancy. For now, Stephen is financially supporting the couple. But Leah hopes to return to Starbucks as a store manager some day.

She doesn’t know how much debt she has accumulated. But she will have to pay back what she owes before she can begin earning a paycheck with Starbucks again.

“I definitely made sure to leave on good terms so that when I come back some day, no matter how we hope to expand our family again in the future, we can have support from Starbucks,” she said.