Reforming Abusive Billing Practices, One Step At A Time

By Christine H. Monahan and Linda J. Blumberg

As hospitals expand in size and scope, including taking over outpatient health care settings, prices for routine medical services are rising, sometimes dramatically. This is a problem in both Medicare and the commercial insurance market because hospitals often bill extra facility fees on top of the professional charges from the physicians or other practitioners who provide care. In the commercial market, the effects of facility fee billing are compounded by the lack of price regulation limiting how much market-dominant hospitals and health systems can charge. The growing size of deductibles, as well as additional, distinct cost-sharing obligations for hospital and physician bills, mean that consumers often directly bear the brunt of these charges.

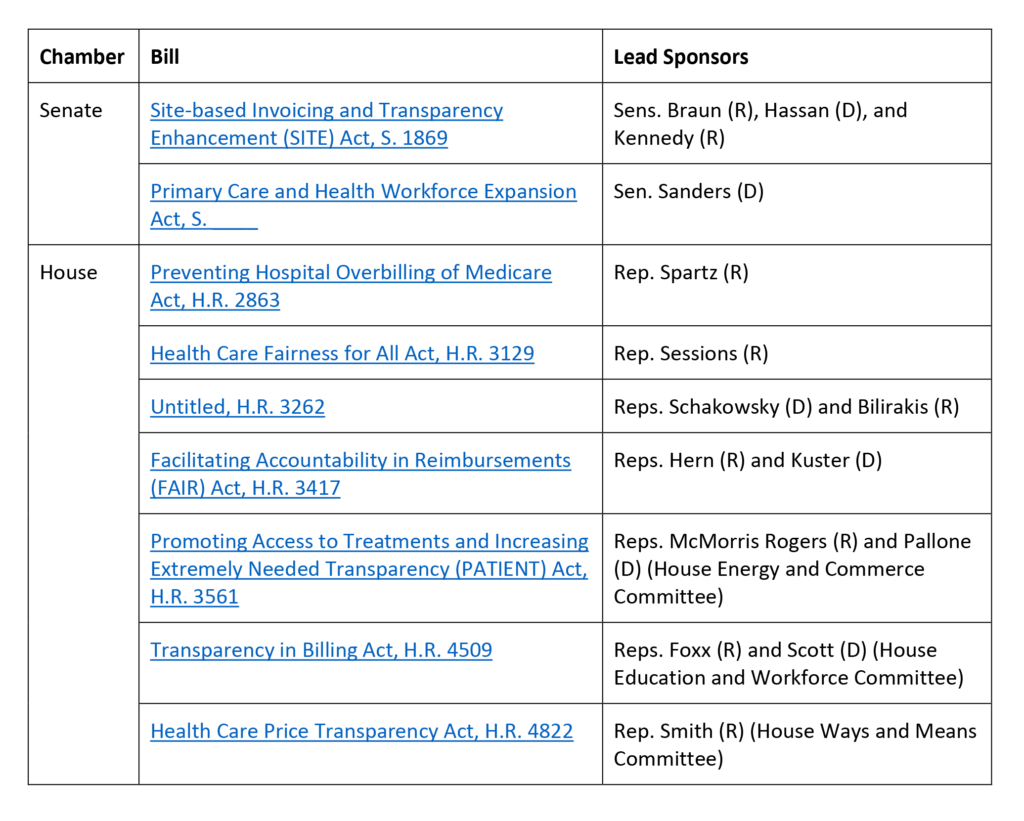

Over the past several years, Congress and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) have taken preliminary steps to rein in facility fee billing in Medicare, but much of the problem remains. Today, Congress is considering several proposals (exhibit 1), most of which are bipartisan, to move the ball forward another step. In this article, we take a closer look at the current slate of proposals to reform abusive billing practices in the commercial market.

Exhibit 1: Current congressional proposals to reform or increase transparency on facility fee billing under commercial health plans

Source: Authors’ analysis.

Price Caps And Site Neutrality In The Commercial Market

By far, the most comprehensive bill floated to date is Senator Bernie Sanders’ (I-VT) Primary Care and Health Workforce Expansion Act. What makes this bill stand out is that it seeks to not only curtail abusive outpatient facility fee billing in the commercial market, as some states have begun to do, but also would impose price caps as a mechanism to achieve site-neutral payments for a meaningful swathe of services.

We have previously discussed the limitations of prohibiting outpatient facility fee charges without including additional pricing constraints. In short, prohibiting hospitals from billing outpatient facility fees without any regulation of the total prices charged allows hospitals with market power to increase the rates their affiliated physicians and other health care professionals charge for those services and otherwise increase prices for other services to make up for the lost revenue. Although such reforms may generate short-term savings, they are unlikely to meaningfully contain costs in the longer run. Adding price caps, at least for a specified set of low-complexity outpatient services commonly provided in physician offices, would limit hospitals’ ability to increase professional fees for outpatient services beyond a specified level. How high or low that payment is relative to existing reimbursement levels, as well as how broadly it applies, will largely determine the potential cost savings. These price caps ultimately may lead insurers to achieve “site neutrality,” paying the same amount for services whether in a hospital or independent setting.

Sen. Sanders’ proposed price caps would reach a relatively broad set of services: all care provided in off-campus outpatient settings as well as low-complexity services provided in on-campus settings, so long as they can be safely and appropriately furnished in off-campus settings as well. This explicitly includes evaluation and management services and telehealth services, as well as other items and services to be determined by the secretary of Health and Human Services. This focus is similar to proposals for site-neutral payments in Medicare from the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission and for limiting facility fees from the National Academy for State Health Policy.

In proposing a payment level for these services in the commercial market, Sen. Sanders is breaking new ground while drawing on an existing concept: the No Surprises Act’s (NSA’s) qualifying payment amount (QPA). Specifically, Sen. Sanders’ proposal would limit providers and facilities to charging one fee that is no greater than the QPA for a covered item or service. This aspect of the bill is sure to invite debate; the calculation of the QPA under the NSA has faced ongoing lawsuits by health care providers and their supporters. It remains to be seen whether reliance on the QPA—or even the commercial price ceiling proposal more broadly—survives beyond this first draft of Sen. Sanders’ bill (which has yet to be formally introduced), but, even if not, Sen. Sanders has opened the door to discussion and debate of a policy approach that warrants attention.

Transparency In Billing

The remaining commercial market billing reforms in Congress focus on improving transparency around outpatient facility fee billing. These proposals are driven by a growing recognition that health care payers, and the researchers, regulators, and policy makers who rely on claims data, have a shockingly poor understanding of where care is provided, by whom, and at what total cost. For example, claims forms often only include the address and national provider identifier (NPI) for hospital’s main campus or billing office rather than the off-campus site of care. Discrepancies between the information on hospital claims (traditionally the UB-04 form, or the electronic equivalent thereof) and professional claims (traditionally the CMS-1500 form, or the electronic equivalent thereof) also make it difficult to reliably associate hospital and professional bills for the service to identify the total price of care. Additionally, outside of registries in individual states such as Massachusetts, there is a lack of publicly available data tracking hospital ownership and control over outpatient providers and settings.

As a result of these information gaps, even insurers with some market leverage may be unable to effectively negotiate with providers on the total price paid for services and cannot assess how much care is being provided in different settings and how the costs compare across these settings. Insurers also may have more difficulty capitalizing on new laws, such as in Texas, that prohibit anti-steering or anti-tiering clauses if they cannot reliably distinguish when care is being provided at different outpatient locations owned by the same health system. Additionally, absent better information, policy makers face challenges evaluating the potential effects of different reforms, and regulators may have difficulty enforcing new laws seeking to rein in abusive outpatient billing practices.

The majority of the currently pending bills largely seek to tackle the lack of location-specific information for the site of care on claims forms. They all would require that hospital outpatient departments, as defined by CMS under the Medicare program, obtain a unique NPI and use this identifier for billing. This 10-digit code would enable payers and other analysts reviewing claims data to know the specific location where care was provided, without the same risk of errors that relying on an address alone would introduce. (Additionally, simply requiring the location’s address without updating the NPI may result in insurer systems rejecting the claims because the address on the claim does not match the address associated with the listed NPI.)

To the extent billing transparency legislation moves forward, Congress will need to iron out technical differences among the existing proposals. One issue is whether just hospitals and facilities need to include the site of care’s unique NPI on claims or if health care professionals must include this information as well. Most of the legislation focuses on hospital bills, but this misses out on an important opportunity. If the site of care’s unique NPI is consistently included on both hospital bills and professional bills, insurers and other analysts will be better able to associate claims for the same service and calculate the total cost of care for each.

Both the House Energy and Commerce Committee proposal from Representatives Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-WA) and Frank Pallone (D-NJ) and the House Ways and Means Committee proposal from Representative Jason Smith (R-MO) require the unique NPI on Medicare billing forms only. Representative Pete Sessions’ (R-TX) Health Care Fairness for All Act requires only that off-campus hospital outpatient departments acquire a unique NPI but does not explicitly require that it be used when claims are submitted. In contrast, other proposals explicitly extend the requirement for use of a unique NPI such that commercial claims cannot be paid without it. Some, such as the Education and Workforce Committee’s bill, even impose parallel requirements that insurers cannot pay and consumers are not liable for claims that do not include the location of care’s unique NPI.

Arguably, even a proposal that is focused on Medicare could benefit the commercial market because regulations under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) require health care providers to use their NPI on all standard transactions. Nonetheless, there is reason to believe bills explicitly extending this requirement to commercial claims and providing more enforcement mechanisms could have better compliance, and thus a bigger impact. First, providers potentially could argue that their original, systemwide NPI is still valid and continue to use that on commercial claims. Second, commercial insurers would need to update their claims processing systems to accept claims with the new unique NPIs, and they may not find the incentive to be sufficiently strong to take this step if the legislation applies only to Medicare billing. If Congress ultimately pursues a Medicare-only reform, it would behoove CMS to amend the HIPAA regulations or issue guidance to ensure the new, unique NPI is required on all commercial claims as well and push insurers to accommodate these changes.

While switching to unique NPIs is a critical step to better understanding location data, it may become harder for payers and researchers to see the system affiliation of the different locations that are now submitting claims. Payers and the broader public would significantly benefit from a comprehensive federal system for tracking hospital ownership and acquisitions, such as that proposed by Representatives Janice Schakowsky (D-IL) and Gus Bilirakis (R-FL). Ideally this system would be designed to complement the unique NPI requirement, so that hospitals and health systems must report all of their affiliated unique NPIs and update this information on a timely basis, on top of other data requirements currently included in the bill. To the extent such a proposal is not adopted, CMS should consider how else it may be able to better collect this information under existing authorities—either leveraging data collected as part of the NPI application or perhaps newly collecting such information through hospitals’ Medicare cost reports.

Looking Forward

The cost consequences of current billing practices are substantial. Consumers need lawmakers to begin curtailing this abusive behavior that puts them at risk of higher cost sharing and medical debt and increases their premiums. The proposals pending before Congress are a critical first step, although outside of Sen. Sanders’ bill, they are also only that—more focused on transparency of information on pricing than on reducing total prices of low complexity services.

Assuming we don’t see significant expansions in the scope of these proposals in whatever package, if any, moves forward, it will fall on CMS, the states, and private payers to keep moving the system forward in the short term. But we should not overstate the impact most of these proposals are likely to have: Insurers in noncompetitive provider markets have little to no leverage in negotiating lower prices for services, even if they are able to obtain better information on pricing. States are starting to tackle this issue but face significant opposition from the hospital industry. What’s more, the primary tactic states have pursued to date—prohibiting facility fee charges for certain outpatient services/settings—can decrease consumer out-of-pocket costs but will not reduce total costs as market-powerful hospitals make up their charges elsewhere, and premiums rise accordingly.

Ultimately, limits on total prices for outpatient care, including facility and professional charges, are necessary to eliminate the growth in these ballooning billing practices that have spread broadly as a consequence of vertical integration in health care.

Authors’ Note

On Wednesday, September 6, 2023, as this article went to production, Axios published a discussion draft floated by Republicans from the House Ways and Means, Energy and Commerce, and Education and Workforce Committees that would require Medicare hospital outpatient departments to obtain a unique NPI and use this for Medicare billing purposes. The bill is expected to be introduced imminently.

This post is part of the ongoing Health Affairs Forefront series, Provider Prices in the Commercial Sector, supported by Arnold Ventures.

Christine H. Monahan and Linda J. Blumberg, “Reforming Abusive Billing Practices, One Step At A Time,” Health Affairs Forefront, September 8, 2023, https://www.healthaffairs.org/content/forefront/reforming-abusive-billing-practices-one-step-time. Copyright © 2023 Health Affairs by Project HOPE – The People-to-People Health Foundation, Inc.