Punishment vs. deportation: What we can learn from the case of the truck driver in the Humbolt Broncos bus crash

Jaskirat Singh Sidhu landed in Canada as a permanent resident in 2014, joining his now wife, Tanvir. After marrying in 2018, Tanvir made the decision to return to school and become a dental hygienist. Sidhu, who has a degree in commerce, earned his license to operate a tractor trailer so he could support his family while his wife finished school.

The licensing process required only a week of instruction and two weeks of solo driving. Sidhu was then legally allowed to operate a tractor trailer.

Sidhu was still a trucking novice when on April 6, 2018, he crashed into the Humboldt Broncos bus. He was convicted of dangerous driving causing death and bodily harm, and sentenced to eight years imprisonment.

Not yet a citizen, he now faces removal from the country, being potentially inadmissible for serious criminality under the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA).

What will Canada achieve by deporting Sidhu?

By the time he’s deported, Sidhu will have served the longest term of imprisonment ever imposed in Canada for the offence committed where the convicted person had not consumed drugs or alcohol and was not otherwise distracted.

To remove him will force his wife, who is now a citizen, to also relocate. Any steps they have taken to improve their lives and contribute to Canada will be lost. So, what does Canada actually gain through deportation? And how do Canadians benefit by deporting Sidhu?

Deciding to remove

The response to Sidhu’s potential removal has been mixed — including among the victims’ family members. Supporters of Sidhu have described his removal as an act of vengeance with no clear purpose. And family members who object to his deportation have highlighted his significant repentance. They similarly question the utility of deportation, acknowledging that Sidhu will have already been punished by the criminal justice system before removal.

Families of victims that support deportation have comparatively characterized Sidhu’s removal as a necessary step towards the achievement of “justice.” They have argued that laws like the inadmissibility provisions in the IRPA are in place because they protect Canadians.

According to these families, it is because of laws like these that Canada is such a great place to live, and why many migrants want to call Canada home. They argue that to not remove Sidhu would then offend legislative requirements.

Sidhu leaves with his lawyers after the third day of sentencing hearings in Melfort, Sask., in January 2019.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Ryan Remiorz

Deportation vs. punishment

Sidhu’s deportation is often positioned as a “punishment.” Regularly described as an act of “vengeance,” a step in the pursuit of “justice” and that it is being imposed based on the commission of the offence.

Yet by deporting Sidhu, Canada is not punishing him for the offence committed.

Deportation is instead imposed based on conviction and sentence. As set out in section 36(1)(a) of the IRPA, a migrant may be inadmissible for serious criminality where they are convicted of an offence carrying a maximum term of imprisonment of 10 years or more, or where they have been sentenced to incarceration for more than six months.

An order for deportation is only rendered following the conclusion of criminal proceedings.

This distinction between punishment and removal was confirmed by the Supreme Court of Canada in R. v. Pham where it was determined that deportation is not a true penal consequence.

Deportation is instead a “collateral consequence” of conviction; it is a civil sanction imposed because of conviction, not as punishment for the actual offence committed.

Rationalizing deportation

If not to punish, then why deport Sidhu?

Arguments for legislation targeting removal have primarily (although not exclusively) characterized migrants as “foreigners” who threaten the safety and security of citizens.

The primary reference to “foreignness” supports expulsion by positioning migrants convicted of offences as outside of the population — migrants are contrasted to citizens as victims. So it is in the interest of Canadians to support deportation of these “threatening outsiders.”

What is crucial here, and in distinction to punishment in the criminal courts, is that the positioning of foreigners as outside of the population further justifies their lack of access to legal rights.

A common saying in support of exclusion is that being in Canada is a privilege, not a right. And when migrants fail to abide by Canadian legislation, they lose this privilege.

By equating removal with punishment, these distinctions between the criminal court and immigration are lost. But recognizing the limits on access to rights in the immigration system is critical.

Following the 2013 passage of Bill C-43, the Faster Removal of Foreign Criminals Act, migrant access to appeal a removal order issued for serious criminality has been significantly restricted. Permanent residents now only retain the right to appeal if sentenced to less than six months imprisonment.

For migrants who have lived in Canada their entire lives and who now face deportation, these limits on access to the right of appeal mean that they can be sent to a country they don’t know, where they have no network of support, all because they have been positioned as “foreign.”

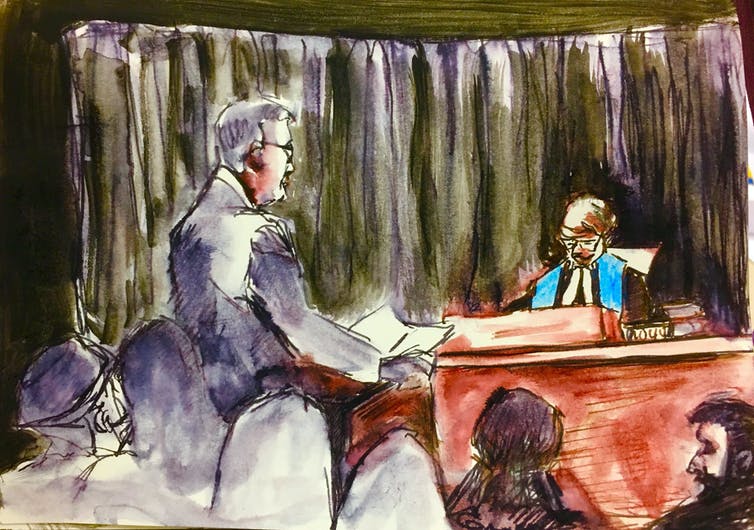

Crown prosecutor Thomas Healey during Sidhu’s sentencing hearing in a courtroom sketch, in January 2019.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Cloudesley Rook-Hobbs

Sidhu is not being deported as punishment. He is being removed because he has been positioned as a foreigner in Canada who has lost the privilege to remain. Removal is used here not as a punishment for what was done, but because of who Sidhu is.

Recognition of the distinction in rationales for punishment and deportation is acute to broader discussions of citizenship. We must be attentive to whose rights are delimited based on the binary between citizens and foreigners that supports deportation. Who is actually captured by these categories? Who is a citizen, who is protected and who is excluded?

While rhetorical, these questions are meant to signal that limits on deportation are a cause for concern for everyone in Canada.