Proposed rule would limit duration of coverage under short-term health plans to 4 months

Since 2018, federal rules have made it possible for consumers in many states to buy short-term, limited-duration insurance (STLDI) and keep that coverage for as long as three years, including renewals and extensions. (States can set their own more stringent rules, which is why these rules don’t apply nationwide.) But a rule proposed by the Biden administration in July 2023 would significantly limit the length of STLDI plans.

If finalized, the rule would limit the initial term of STLDI policies to no longer than three months. Though the rule would allow renewal of a policy, the total duration of a plan would be limited to four months, and a buyer would not be allowed to purchase another short-term plan from the same insurer within 12 months of their initial policy effective date.

The agencies publishing the rule noted that these changes are designed to ensure that short-term coverage is used to fill a temporary gap between two comprehensive policies, rather than serving as a long-term coverage solution. The rule is also intended to reduce the number of people who inadvertently purchase short-term coverage when trying to buy comprehensive coverage.

In introducing the proposed rule, President Biden said his administration is “cracking down” on limited-duration insurance being sold to individuals who often don’t understand the coverage and then are surprised when they get hit with large medical bills.

The proposed change would roll back a 2018 rule that expanded the availability of short-term, limited-duration plans, allowing them to last for up to three years if the coverage is renewable.

According to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners, 235,775 people were covered under short-term policies as of 2022. However, the actual number of enrollees is uncertain because insurance carriers are not required to report enrollment data.

What happens next?

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is accepting public comments on the proposed rule until September 11, 2023. Rulemaking is a multi-month process, so any rule change likely won’t be finalized until late 2023.

If approved, the rules would not apply to new short-term policies until 75 days after the rule is finalized. Policies issued before that date would not have to comply with the new rules.

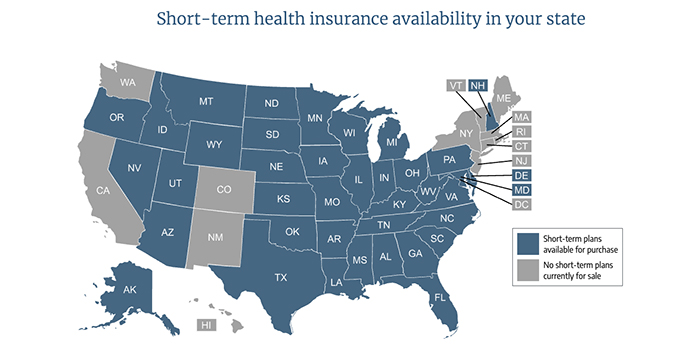

For now, consumers in many states can continue enrolling in longer-duration short-term plans. We say “many states” because although the 2018 rule permits states to allow the sale of longer-duration plans, nearly half of the states have adopted stricter limits on STLDI duration. (See details below for each state.)

Some states have banned the sale of short-term plans outright while other states have adopted regulations that have caused insurers to stop selling the plans.

The Biden administration’s proposed changes

The proposed rule published in July 2023, would change all three of the rules that the Trump administration put in place. Those 2018 rules:

Limit short-term plans to initial terms of up to 364 days.

Allow short-term plans to be renewed as long as the total duration of the plan doesn’t exceed 36 months.

Require short-term plan information to include a disclosure to help people understand how short-term plans differ from individual health insurance.

Under the Biden administration’s proposed rule:

New short-term policies would be limited to initial terms of no more than three months.

Carriers would be able to offer renewable policies, but the total duration – including renewals – could not exceed four months. The proposed rule notes that the three-month window is designed to align with the maximum waiting period that a new employee can be subject to before being eligible for an employer-sponsored health plan.

A consumer would not be allowed to purchase an additional short-term policy from the same insurer within 12 months of the effective date of the first policy.

The required disclosure notice would be updated to clarify that federal financial assistance is not available with short-term policies, and that surprise balance billing protections do not apply to these policies.

State regulatory flexibility regarding short-term plans

As noted above, HHS made it clear in the 2018 regulations that although the federal rules expanded the limits on short-term plan duration, states may continue to implement more restrictive rules, just as they did prior to 2017. (States cannot implement rules that are more lenient than the federal regulations.)

States are taking varying approaches on short-term plans, with some clearly wanting to expand access, while others prefer to restrict or eliminate short-term plans in an effort to protect their ACA-compliant markets.

In a few states – New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Vermont – short-term plans weren’t sold at all as of 2018. And by 2020, five additional states – California, Colorado, New Mexico, Maine, and Hawaii – and Washington, DC also had no insurers offering short-term plans.

In Washington, the sale of short-term health plans was discontinued in mid-2022 and no insurers offer short-term health plans in Washington as of 2023. New Hampshire and Minnesota also had no insurers offering short-term health plans by mid-2023.

In addition, several states had already capped the duration of short-term plans at three or six months, even before the Obama administration took action to limit short-term plans. Other states have subsequently implemented three- or six-month caps on short-term plans.

Ultimately, there are more states with their own restrictions on short-term plans than there are states that are defaulting to the federal rules. Use this map to see how states restrict short-term plans.

If the Biden administration’s proposed rules are finalized, states will no longer have the option to allow short-term policies to have initial terms of more than three months, or total durations of more than four months. Policies with longer terms would not be considered short-term plans and would have to comply with the ACA’s rules for individual-market coverage.

Current state limits on duration of short-term plans

States allowing short-term plans to have duration up to six months

Colorado – Six-month initial durations are allowed, but insurers stopped offering short-term plans as of 2019.

Connecticut

Illinois limits initial plan duration to six months with no renewals.

Michigan limits initial plan durations to 185 days with no renewals.

Minnesota limits initial plan durations 185 days, but no insurers offer plans as of August 2023.

Nevada limits initial plan durations to 185 days with no renewals.

New Hampshire limits initial plan durations to six months and 18 months total within a two-year period, but no insurers offer plans as of 2023.

States (and the District of Columbia) allowing short-term plans to have duration up to three months

A handful of states allow short-term plans to have initial terms in line with the new federal rules (364 days), but place more restrictive limits on renewals and total plan duration:

Idaho – “Enhanced” short-term plans are guaranteed renewable for total duration of three years. State limits initial duration of non-enhanced short-term plans to six months with no renewals.

Kansas – (Only one renewal permitted.)

Ohio – (Renewals not permitted.)

South Carolina – (11-month maximum initial term, and 33-month maximum duration.)

Wisconsin – (Total duration limited to 18 months.)

In 14 states and the District of Columbia, no short-term plans are available for purchase. In some cases, state regulations ban sale of the plans outright. In others, state regulations make it unappealing for insurers to offer short-term plans.

California – State law prohibits the sale of short-term plans.

Colorado – As noted, plans are technically allowed with six-month initial durations, but insurers have stopped offering short-term plans.

Connecticut

District of Columbia – Plans are allowed for up to three months with no renewals, but no insurers offer them.

Hawaii – As noted, no insurers offer plans under the rules the state implemented.

Maine – New rules took effect in 2020, and no insurers offer plans.

Minnesota – No insurers offer plans as of August 2023.

New Hampshire — No insurers offer plans as of 2023.

New York

New Jersey

Massachusetts – Health plans are required to be guaranteed-issue, so short-term policies are not available in the state

New Mexico – State regulations limit the plans to three months and prohibit renewals, but no insurers were offering plans as of mid-2019.

Rhode Island – STLDI is not banned, but state rules are strict enough that no insurers offer these policies

Vermont – There are no short-term plans available in Vermont, but legislation was also enacted in 2018 to limit short-term plans to three months and prohibit renewals, in case any plans are approved in the future.

Washington – Plans are allowed for up to three months, but no insurers offer them.

You can use the map on this page to see more details about short-term health insurance rules and availability in each state.

The path to current short-term federal rules

Under regulation changes that HHS finalized in 2018 – and in effect since October of 2018 – the initial duration of short-term plans was lengthened to 364 days with an option to renew a plan for coverage up to a total of three years. This 2018 rule reversed regulations – put in place by the Obama administration – that had limited short-term plan durations to 90 days and did not allow renewal of policies.

The 2018 rule also established that a plan is considered “short-term” as long as it has an initial term of less than a year (no more than 364 days).

But the 2018 rule also allows short-term plans to offer enrollees the option to renew their plans without additional medical underwriting and use renewal to keep the same plan in force for up to 36 months.

Under the Trump administration, HHS justified this by noting that the coverage has long been called “short-term limited duration” health coverage, and pointing out that “short-term” and “limited duration” must mean different things, otherwise the phrases would be redundant.

So HHS said that “short-term” refers to the initial term, which must be under 12 months. But they allowed the “limited duration” part to mean up to 36 months in total, under the same plan.

It’s important to note that HHS may have expected this to be challenged in court, as they included a severability clause for the part about 36-month total duration: If a court were to strike down that provision, the rest of the rule would remain in place. (A lawsuit was filed over the legality of the new short-term insurance rule in September 2018, but that case ended with a ruling in favor of the Trump administration.)

In the 2018 rule, HHS noted that there is nothing in federal statute that would prevent a person from enrolling in a new short-term plan after the 36 months (or purchasing an option from the initial insurer that will allow them to buy a new plan at a later date, with the new plan allowed to start after the full 36-month duration of the prior plan).

So technically, federal rules allow people to string together multiple “short-term” plans indefinitely. But as noted above, there are quite a few states with much stronger short-term plan regulations, and some states implemented restrictions on short-term plans specifically in response to the new federal rules.

The disclosure notice required in the 2018 rule was intended to inform consumers of several aspects of short-term coverage: That the plans are not required to comply with the ACA, may not cover certain medical costs, and may impose annual/lifetime benefit limits. The disclosure also notes that the termination of a short-term plan does not trigger a special enrollment period in the individual market (although it does for group health plans).

Enrollees who develop health conditions while covered under a short-term plan – and may be subject to pre-existing condition exclusions under a new short-term plan – might find themselves without short-term coverage and having to wait until the next open enrollment period to sign up for Marketplace coverage.

Louise Norris is an individual health insurance broker who has been writing about health insurance and health reform since 2006. She has written dozens of opinions and educational pieces about the Affordable Care Act for healthinsurance.org. Her state health exchange updates are regularly cited by media who cover health reform and by other health insurance experts.