Pierre restores an AC 3000 ME, the car his father helped create 50 years ago

Fresh from the pages of Practical Classics Magazine, we meet Pierre Bohanna, who has restored the AC 3000 ME his father helped to create over 50 years ago, and Nick Favell, who restored his family’s Vauxhall Magnum Sportshatch for his brother-in-law’s 60th birthday.

As a specialist classic car insurance broker, we love seeing old cars being restored to their former glory, which is why we’ve linked up with Practical Classics to bring you two fantastic stories each month for you to digest and take as inspiration for your own classic rebuilds.

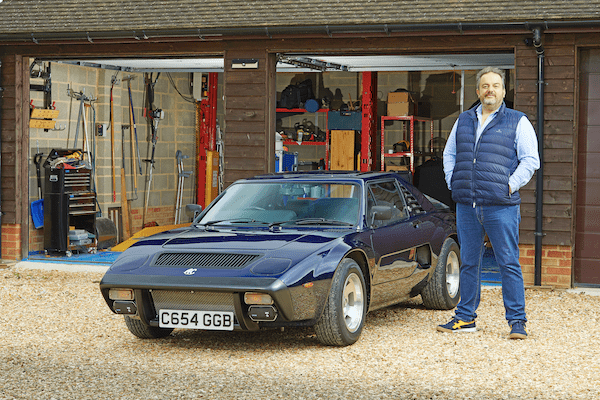

Pierre Bohanna restores the AC 3000 ME that his dad helped create half a century ago

Words by John Simister and Pictures by Matt Howell

Father-and-son tales always warm the heart when there’s a restoration involved. Two generations sharing a common task, with a shiny, resurrected car the rewarding result. For this AC 3000 ME, though, the idea takes on a whole new twist: in this case, the father designed the car.

And now, to honour the much-missed father’s memory, the son buys a very tired example made towards the end of a troubled production run, and restores it to better-than-new condition. Meet Pierre Bohanna, son of the late Peter, his French wife Jacqueline, and his fabulous 1985 AC that’s the last-but-one of the model to be built.

So, what exactly is an AC 3000 ME? It’s mid-engined, obviously, and it was AC’s plan for a post-Cobra (and post-invalid carriage – remember those tiny, pre-Motability, single-seaters in pale turquoise?) future. But it wasn’t entirely AC’s own design any more than the Ace or the Cobra were. At the 1972 Racing Car Show there was displayed a neat, mid-engined, two-seater sports coupé called Diablo, designed as a possible kit car and powered by an Austin Maxi engine. It was the work of two men who had worked for the Lola racing car company, designer Peter Bohanna and finance man Robin Stables.

They created it in their workshop near Stokenchurch, Bucks. It was quite a family affair: “I used to lay the fibreglass and clean the moulds,” remembers Jacqueline today. But British Leyland wouldn’t agree to supply engines, and the Diablo appeared at the show with an uncertain future until AC boss Derek Hurlock came on the stand. A deal was done, and the seed for the 3000 ME was sown. “AC didn’t actually do anything for quite a long time, though,” Pierre tells us, “nor did they pay. Peter and Robin were not what I would call businessmen.”

They got some money for their design in the end, but probably should have got more. Meanwhile AC, with help from Bohanna and Stables, began to set about altering the Diablo to its needs, changing the tubular chassis for a sheet steel one and opting for a 3.0-litre Ford Essex V6 engine. The new car appeared at every Earls Court, and later NEC, motor show over the next few years, with production always ‘imminent’, but delays, including the need to conform to changing crash-test rules, meant that you couldn’t buy a 3000 ME until 1979.

Peter Bohanna and Robin Stables went on to create the Nymph kit car, an Imp-based take on the Citroën Méhari idea, then parted company after maybe 20 had been made. Later, Peter went into the world of film props, including the Lotus Esprit submarine in the Bond film The Spy Who Loved Me. Before then, though, Peter had a couple of ME prototypes to drive: Pierre remembers a “chocolatey muddy brown one and another in a mushy camouflage pea-green. One of my earliest memories was sitting in the passenger seat and not being able to see over the dashboard.”

The first road tests of the AC 3000 ME were not as enthusiastic as the car’s credentials suggested they should have been. Motor magazine was so concerned at the snap lift-off oversteer it tried to get the factory to remedy the fault before any cars were delivered to buyers. A change of tyre specification tamed the tail, but the price was too high and AC managed to sell just 76 cars before production at the Thames Ditton factory stopped in 1984.

It then restarted under a new company, Glasgow-based AC Cars (Scotland) plc, which managed 30 more cars sold at a more competitive price before pulling the plug the following year.

But the AC stayed special to Pierre. “I was always going to own a 3000 ME one day,” he says. “Many years after my father passed away I started a business with one of his friends, Patrick Griffin. In 2013 I saw car number 211, the last but one to be made in Glasgow, for sale at a Brightwells auction. It had issues, but would make a great project for us to do together. I thought it would go for about £12,000, but we set the bar at £18,000.”

Pierre and Pat were far from the only ones after the AC, but by £17,000 just two bidders were left. The other bidder worked the price up to £17,900, so Pierre put in one more bid at his £18,000 ceiling – and got the AC, to much applause.

“It had lurked under a tarpaulin in Glasgow for 12 years, and the paint was blistered and horrible. So after a few months of replacing minor odds and ends I sent it off for a repaint at Mech Spray in Rochester.”

With the original black paint removed, the fibreglass body was found to be in good shape apart from evidence of a little knock at the front. Mechspray’s Peter and Wayne repaired the damage, reinstated the black, added a dust of metallic particles and finished off with blue-tinted lacquer to create the deeply lustrous dark blue we see today.

Pierre soon realised his keenness to make the AC look good had got ahead of him. The front and rear sections of the last few 3000 MEs’ chassis were galvanised, but not the central tub which in this case, he says, “was completely shot”. The best plan was to make a complete new chassis, so Ian Winter from the AC Owners’ Club lent Pierre a spare one which a work colleague, David Merryweather, could copy in CAD drawings. From these the chassis was built up in stainless steel by Barry and Clive at BWB Engineering in Ashford, Middlesex, whom Pierre had known since his early twenties.

When the time came it proved to be a perfect fit, but we’re getting ahead of ourselves. “I now realised that I would have to take the whole car apart, which was exciting as a first project but also a bit daunting,” Pierre says. Meanwhile his life was getting busier and Pat’s health was failing, so car 211, great on top but tragic underneath, sat in the garage doing nothing for a few years.

Around this time, Pierre ordered an MGB LE Abingdon Edition from Frontline Developments, a brilliant more-than-restomod with a tuned NC-generation MX-5 engine. “That process took about two very enjoyable years, and I became good friends with Tim Fenna and Ed Braclik who owned Frontline. Could they do the stripdown and rebuild for me? Despite how busy they were, they agreed to take it on. Two of their guys, Andy and Bill, did the hard work, mostly Andy, but with Bill finishing off and doing the electrics.”

Sounds simple, summed up like that. But there was a huge amount to do, not least because Pierre wanted to incorporate a few improvements. One of these was a new instrument and switch panel, machined from one piece of solid aluminium – including the dial bezels – by Jim at Wycombe Engineering, one of Pierre’s useful contacts in the world of film props.

It replaces the former two pieces of leather cloth-covered aluminium sheet with Jaguar XJ6 switches, but the original instruments are retained, the minor ones now slightly angled towards the driver. Most of the original wiring loom remains, too, with extras added by Bill. Frontline then retrimmed all the interior apart from the seats, and a heated windscreen came from a batch made by the AC Owners’ Club.

There were the composite bumpers to fix, too, which is where Pierre’s work in making moulded film props helped. “The originals had started to degrade and didn’t fit well,’ he says, ‘so we built new patterns. A pre-shaped foam block is placed into the pattern and a urethane skin is cast around it.”

On the mechanical side, Classic and Modern in Bracknell rebuilt the transversely-mounted 2994cc V6 with, says Pierre, “a slightly funkier camshaft”. A new Weber carburettor breathes through a K&N filter, there’s a new electric fuel pump to cure vapour locks, a new ‘saddle’ petrol tank to feed it, and the whole ensemble delivers around 160bhp instead of the original 138.

And it looks great, thanks to a bespoke pair of rocker covers again machined from solid by the talented Jim. To cure some surge and shunt, Frontline added steady bars in front of and behind the engine to stop it rocking.

Then there’s the five-speed gearbox, using Maxi internals in AC’s casing and driven by chain from the engine. Graham at Custom Gearboxes did the rebuild: “He was gruff at first, but his attitude totally changed once he got started. ‘It’s like a Dino gearbox,’ he said, “and I’m not letting any other idiots near it.”

As you would expect in a low-volume sports car, there are proprietary parts: rear lights from a Triumph, rear hub bearings shared with a Ford RS200 (they’re £700 a pair), a pair of fuel fillers from a Jaguar XJ6. One was beyond salvation, but Pierre found another from an old XJ6 being used as a film prop.

And tyres, given the handling trouble back in 1979? “Originally they were 205/60 R14 all round, but nowadays the experts say they should be 195/60 at the front and 215/60 at the back. It feels fine to me.”

So, is there anything left to do? “The catch for the pop-up sunroof has always been a weak design and this one is broken at one end. The club is planning to make some more.”

Finally, in June 2021, C654 GGB was finished. “It was eight years since she came into my world,” Pierre recalls. “Tim Fenna brought it over to my house, then I drove it over to Goring where my mother lives. I called her: ‘I’m on the drive.’ When she came out and saw the car, it was very emotional for both of us.”

What is it like to drive?

It’s a beautiful restoration of an already good-looking machine, with an almost new-car crispness. And that V6 sounds great as the AC burbles out towards the main road. I’m sitting low and reclined, a compact steering wheel fronting that delicious machined dashboard and its precisely acting switches, gearchange rendered mechanical-feeling by an open gate that’s pure Ferrari fantasy. And also true to its Maranello inspiration, the shift doesn’t like to be rushed.

The gearing is quite long-legged, but the engine has the torque to cope. It’s punchier than past road tests suggested, thanks to the better-breathing camshaft, and at higher revs it takes on a proper snarl.

Read the full version of how Pierre managed to restore this AC 3000 ME on the Practical Classics page.

Restoring the family’s Magnum Sportshatch for my brother-in-laws 60th

Words by Nigel Clark and Pictures by Matt Howell

Nick Favell can turn his hand to any challenge, including the family Magnum. Asked about his first interest in the world of cars, Favell recalls his earliest childhood memory of sitting in the back of a Jaguar Mk VII, driven by his father not long after Favell senior had passed his driving test in the sixties.

“I remember the unusual opposing wiper arrangement on the Mk VII’s split windscreen, and being told off for sticking my arm out the rear door quarterlights!” He laughs.

Jumping forward two decades to the early eighties, Nick found a part-time job as a forecourt attendant at a local Leicestershire Jet service station, where the owner quickly recognised young Nick’s drive and determination, giving him an opportunity on the spanners. “I was able to combine my workshop job with part time technical college study, gaining a City & Guilds motor vehicle qualification.”

After a few years, he became an AA patrolman, and then became his own boss. “I set up ‘Mr Clutch’, a specialist clutch fitting service based in a workshop in Leicester.” This grew successfully for several years before Nick chose to move on again, working in garages including a Vauxhall main dealership, then in 2000 he set up alone as a mobile mechanic operation. This nomadic existence continued until 2004, when he decided to buy the proper bricks and mortar premises he occupies to this day in the Leicestershire village of Countesthorpe.

Clearly Nick has long had a personal interest in classic cars: “local enthusiast John Bowyer had been bringing his Zodiac Executive in for MoT when I took over here and he continued to come here. Then when John wanted a sympathetic workshop to restore his Zephyr, he brought that to me as well. After a number of other jobs word spread that we were interested in looking after classic cars at Favell’s Garage.”

Pride of place in Nick’s collection goes to his very original and well-presented Vauxhall Magnum Estate, which has been owned by his family from new since 1974. Nicknamed ‘Maggie the Magnum,’ it’s well known in Vauxhall club circles, as it’s rare to find a seventies Magnum surviving in such fine condition.

First owned by Nick’s sister’s late father-in-law, remarkably this car has been in the family since new. Finished in rare olivine green metallic, it passed to Nick’s brother-in-law in the mid-nineties, by which time typical old car problems were developing. Corrosion was taking hold around the windscreen, scuttle and one of the front wings, and the front suspension needed rebuilding. It sat in a garage as a stalled project until Nick took it under his wing.

“The initial aim was to get it back on the road for my brother in law’s sixtieth birthday.” Nick’s brother-in-law couldn’t help but realise Nick had the Vauxhall in his workshop, but had no inkling of the extent of the work being carried out, or the planned sixtieth birthday deadline.

The corrosion repairs were challenging, as the required panels weren’t available. Nick hand fabricated floor repair panels and an inner sill from scratch, but discovered for the outer sill that a Ford Ka panel could be adapted as it was a similar shape. After cutting out the rot and welding the new panels in, the repaired areas were repainted. Similarly, new metal was carefully shaped and grafted into the scuttle, windscreen frame and the rotted nearside front wing, with the affected areas being painted.

Turning to mechanical work, Nick says: “the front suspension had suffered the usual wear over the years, so I replaced bushes and ball joints on both sides. Fortunately, unlike the body panels, these suspension parts were all available off the shelf.”

With these essential repairs completed, the gleaming and now roadworthy Magnum was duly presented back to Nick’s brother-in-law as planned on his sixtieth birthday. The car was admired by knowledgeable show-goers as much for its rarity as its condition and history.

In 2014, the car passed to Nick himself; some extra work was necessary. He sorted yet more corrosion, a stuck clutch and had the car fully resprayed. Nick explains “the paint had become non-standard over the years, with various panels not properly matched. I had it fully resprayed back to the original olivine green metallic.”

Asked about the future, unsurprisingly the Magnum will always remain in the family. Nick still has some jobs planned to improve it further: “next, I will get the alloy wheels refurbished, and in a couple of years I would like to go right through the engine bay, cleaning and repainting, to bring it up to the standard of the exterior.”

As for other impending projects, first he wants to get his Standard Ten back on the road as a daily driver. However, he does admit to a couple of classic pipedreams: “I’ve always fancied a Triumph Stag, and would also like a Jaguar Mk VII.” The Jag is of course the car his father owned and first inspired his interest in all things automotive.

Asked about the Stag, he says: “I love the look of Triumphs from that era, the Michelotti styling. Four-seater convertibles are also a rarity and that’s another reason it appeals to me.”

Nick’s story is one of classic dedication: dedication to looking after his customers’ classics, and dedication to his own projects in his spare time. Only a brave and skilled bodywork expert who grappled with a deeply corroded 1970s Vauxhall… and who but a committed classic car fanatic would choose a Standard Ten as daily transport? All power to him.

Read the full version of how Nick managed to restore his family’s Magnum Sportshatch on the Practical Classics page.