Opioid Overdose Death Rate for U.S. Black Population Is Higher Than for White – The Wall Street Journal

The fatal overdose rate among Black people surpassed that for white people in the first year of the pandemic, as an increasingly lethal drug supply and Covid-19’s destabilizing effects exacted a heavy toll on vulnerable communities in the U.S.

The proliferation of the potent opioid fentanyl, and a pandemic that has added hazards for people who use drugs, are driving new records in U.S. overdose deaths, and Black communities have been hit especially hard. Black people often have uneven access to healthcare including effective drug treatment, putting them at high risk, researchers and public-health experts say.

The most recent full-year of federal data, through 2020, shows the rate of drug deaths among Black people eclipsed the rate in the white population for the first time since 1999, researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles recently demonstrated.

The gap in overdose rates between the Black and white populations was narrowing before the pandemic.

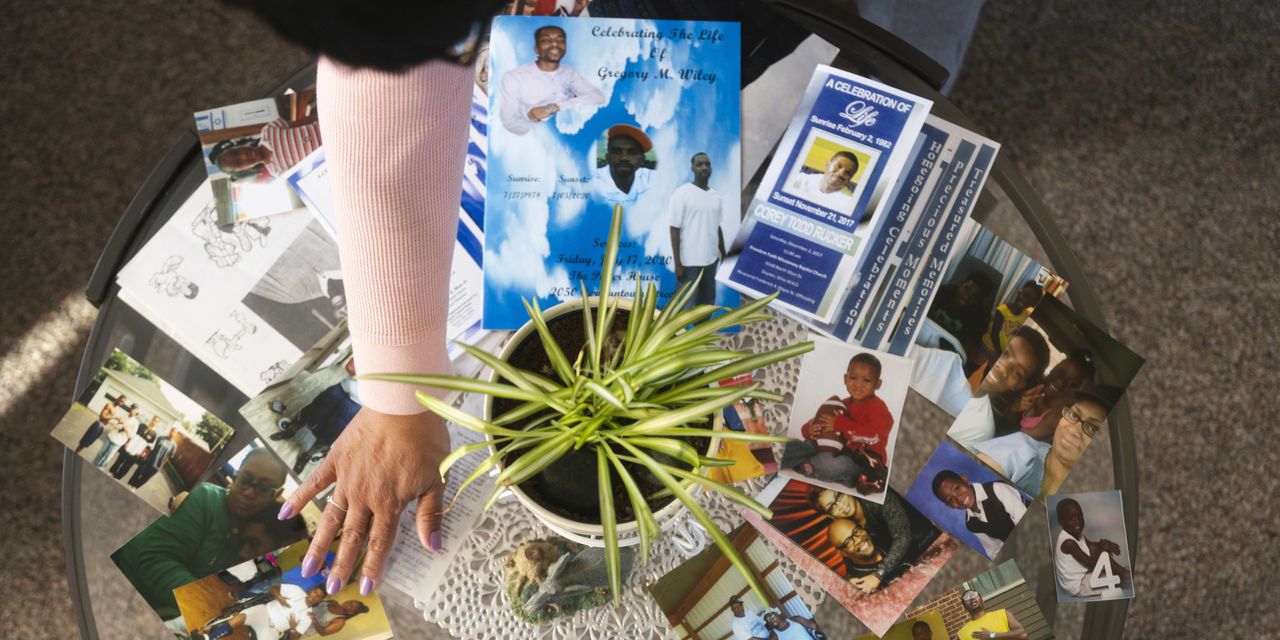

Iris Lattimore

lost her 35-year old son,

Corey Rucker,

to a fatal overdose in late 2017. Her older son,

Greg Wiley,

overdosed and died at age 41, in July 2020. She said assistance and messaging around the crisis seemed aimed at white people rather than her community.

“We’ve been fighting this for a long time,” said Ms. Lattimore, 61 years old.

Family photos of Iris Lattimore’s sons, Corey Rucker and Gregory Wiley.

Iris Lattimore shares a family photo taken when her sons were young.

There were more than 15,200 overdoses among Black people in 2020, more than double the number from four years earlier, according to data the UCLA researchers published in March in the medical journal JAMA Psychiatry. The toll represents nearly 37 drug overdose deaths per 100,000 Black people that year, the UCLA researchers found, trailing only the death rate in the significantly smaller American Indian or Alaska Native population.

“The Black death rate rose much faster than the white death rate,” said

Helena Hansen,

co-author of the new paper and professor of psychiatry at UCLA’s David Geffen School of Medicine.

The researchers said the findings demonstrate the need to close gaps in access to treatment and harm-reduction services, which are meant to make drug use less risky, among other steps. They said ending routine incarceration of drug users could help prevent fatal overdoses among people after they leave prison.

In Boston, opioid-related overdoses in the Black population doubled to 82 in 2020 versus the prior year, while opioid deaths in the city’s larger white population increased 16% to 101. The city has stepped up efforts to bring mobile harm-reduction services to Black communities, said

Bisola Ojikutu,

executive director of the Boston Public Health Commission. This includes distribution of the overdose-reversal drug naloxone and other services like syringe exchanges and testing for HIV and other health issues.

“We have to go where people are,” Dr. Ojikutu said.

The increase in overdoses among Black people comes as fentanyl, a synthetic opioid up to 50 times as powerful as heroin, continues to pour into the U.S. There are legitimate forms of fentanyl used to treat pain, but the main version wreaking havoc in the U.S. is illicitly made by Mexican cartels and smuggled into the U.S., federal authorities say.

Fentanyl was a major driver when drug overdose deaths jumped roughly 30% to about 92,000 in 2020, the most recent federal count for that year shows. The scourge is getting worse: There were an estimated 104,288 overdose deaths in the 12-month period running through September, according to the most recent preliminary data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Use of stimulant drugs like cocaine among Black people may also be exposing some to fentanyl, which sometimes contaminates other drug supplies, health experts say. A recent paper published in the American Journal of Epidemiology found Black Americans had a sharper increase in combined stimulant and opioid deaths than did white people between 2007 and 2019, especially in the eastern U.S.

Fatal overdoses among Black people more than doubled in a recent four-year period, largely due to illicit pills laced with fentanyl, such as these at a Sacramento, Calif., crime lab.

Photo:

Andri Tambunan for The Wall Street Journal

Black people can also face higher hurdles to getting effective care for opioid use, doctors and public-health researchers say. Researchers at the University of Michigan examining outpatient visits for substance use in recent years found white patients were three to four times as likely as Black patients to receive buprenorphine, a prescription medication to treat opioid dependence that is more readily available to people with health insurance or the means to pay out of pocket.

Newsletter Sign-up

Coronavirus Briefing and Health Weekly

Get a weekly briefing about the coronavirus pandemic and a Health newsletter when the crisis abates.

Health providers are more likely to direct Black patients to methadone, which is delivered by highly regulated opioid-treatment programs that often require daily visits to obtain the medication, researchers have found.

The history of Black Americans facing a higher rate of criminal penalties and incarceration for drug-related offenses than whites has also made some Black drug users reluctant to seek help, researchers and treatment specialists say.

“I would wait until I was almost dead to go to the hospital,” said Chetwyn “Arrow” Archer II, 62 years old and a former opioid user who is now a peer-support specialist with IDEA Exchange at the University of Miami, which provides harm-reduction services to drug users.

Ms. Lattimore’s eldest son, Greg, had a criminal record that made it challenging for him to find consistent work as an adult, she said. He appeared to be on the upswing in mid-2020, when he had found a new job at a factory and planned to marry his longtime fiancée. That July, the fiancée found Greg in the basement at their Columbus, Ohio, home, dead from an overdose.

Ms. Lattimore keeps a blanket she made with her two sons’ photos by her side. “Some days I look over at it and I say, ‘I can’t believe you guys left me,’ ” she said.

Iris Lattimore displayed the blanket with her sons’ photos that she keeps close by, in her Ohio home.

Write to Jon Kamp at jon.kamp@wsj.com and Julie Wernau at Julie.Wernau@wsj.com

Copyright ©2022 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8