Millions of people across the US use well water, but very few test it often enough to make sure it’s safe

About 23 million U.S. households depend on private wells as their primary drinking water source. These homeowners are entirely responsible for ensuring that the water from their wells is safe for human consumption.

Multiple studies show that, at best, half of private well owners are testing with any frequency, and very few households test once or more yearly, as public health officials recommend. Even in Iowa, which has some of the strongest state-level policies for protecting private well users, state funds for free private water quality testing regularly go unspent.

Is the water these households are drinking safe? There’s not much systematic evidence, but the risks may be large.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency still relies on a 15-year-old study showing that among 2,000 households, 1 in 5 households’ well water contained at least one contaminant at levels above the thresholds that public water systems must meet. While other researchers have studied this issue, most rely on limited data or data collected over decades to draw conclusions.

I’m an economist studying energy and agriculture issues. In a recent study, I worked with colleagues at Iowa State University, the University of Massachusetts Amherst and Cornell University to understand drinking water-related behaviors and perceptions of households that use private wells. We focused on rural Iowa, where runoff from agricultural production regularly contaminates public and private drinking water sources.

Basic components of a private water well.

EPA

We found that few households followed public health guidance on testing their well water, but a simple intervention – sending them basic information about drinking water hazards and easy-to-use testing materials – increased testing rates. The burden of dealing with contamination, however, falls largely on individual households.

Nitrate risks

We focused on nitrate, one of the main well water pollutants in rural areas. Major sources include chemical fertilizers, animal waste and human sewage.

Drinking water that contains nitrate can harm human health. Using contaminated water to prepare infant formula can cause “blue baby syndrome,” a condition in which infants’ hands and lips turn bluish because nitrate interferes with oxygen transport in the babies’ blood. Severe cases can cause lethargy, seizures and even death. The EPA limits nitrate levels in public water systems to 10 milligrams per liter to prevent this effect.

Studies have also found that for people of all ages, drinking water with low nitrate concentrations over long periods of time is strongly associated with chronic health diseases, including colorectal cancer and thyroid disease, as well as neural tube defects in developing fetuses.

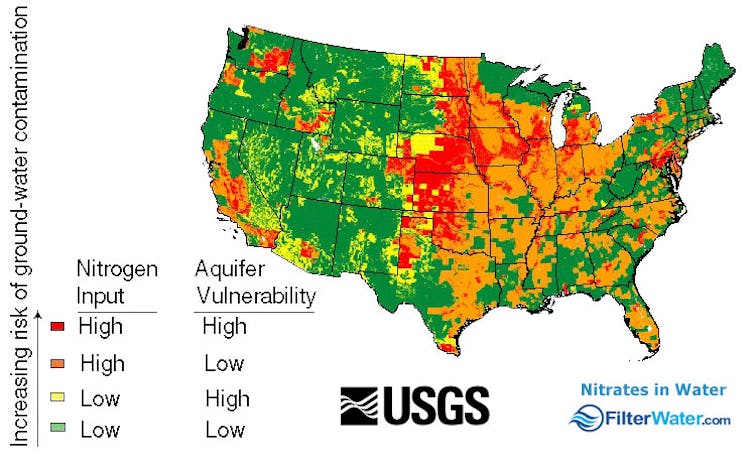

Nitrate pollution is pervasive across the continental U.S. Fortunately, it is relatively easy to determine whether water contains unsafe nitrate concentrations. Test strips, similar to those used in swimming pools, are cheap and readily available.

Heavily agricultural areas are vulnerable to nitrate pollution in water, especially where aquifers are shallow. Areas at the highest risk of nitrate contamination in shallow groundwater generally have high nitrogen inputs to the land, well-drained soils and high ratios of croplands to woodlands.

USGS

The water’s fine … or not

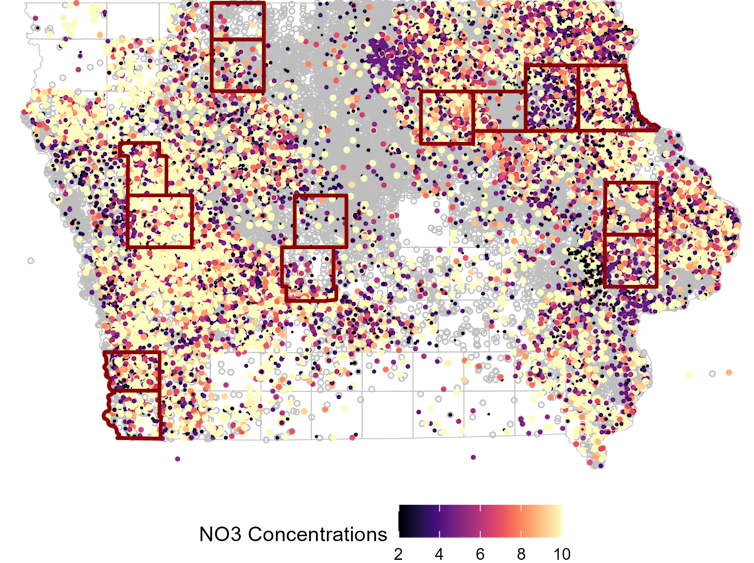

Mailing lists of households with private wells are hard to come by, so for our study we digitized over 22,000 addresses using maps from 14 Iowa counties. We targeted counties where public water systems had struggled to meet EPA safety standards for nitrate in drinking water, and where private wells that had been tested over the past 20 years showed nitrate concentrations at concerning levels.

We received responses from over half of the households we surveyed. Of those, just over 8,100 (37%) used private wells.

Nitrate measurements in domestic wells in Iowa from 2002 to 2022, from the Iowa Department of Natural Resources public water-testing program. Counties targeted in Lade et al.’s 2024 review are highlighted in red.

Lade et al., 2024, CC BY-ND

Although the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends testing annually for nitrate, just 9% of these households had tested their water quality in the past year.

More concerning, 40% of this group used their wells for drinking water, had not tested it in the past year, and did not filter the water or use other sources such as bottled water. They were drinking straight from the tap without knowing whether their water was safe.

Our survey also showed that, despite living in high-risk areas, 77% of households classified their well water quality as “good” or “great.” This may be driven by a “not in my backyard” mentality. Households in our survey were more likely to agree with the statement that nitrate is a problem in the state of Iowa than to perceive nitrates as a problem in their local area.

Climate change is likely to worsen nitrate contamination in well water. In regions including the Great Lakes basin, increases in heavy rainfall are projected to carry rising amounts of nutrients from farmlands into waterways and groundwater.

Nitrate contamination is often thought of as a rural problem, but in California it also has shown up in urban areas.

Providing information and tools helps

To see whether education and access to testing materials could change views about well water, we sent a mailer containing a nitrate test strip, information about risks associated with nitrate in drinking water, and contact information for a free water quality testing program run by the state of Iowa to a random 50% of respondents from our first survey. We then resurveyed all households, whether or not they received the mailer.

Over 40% of households that received test strips reported that they had tested their water, compared with 24% of those that did not receive the mailer. The number of respondents who reported using Iowa’s free testing program also increased, from 10% to 13%, a small but statistically meaningful impact.

Less encouragingly, households that received the mailer were no more likely to report filtering or avoiding their water than those that did not receive the mailer.

Households bear the burden

Our results show that lack of information makes people less likely to test their well water for nitrate or other contaminants. At least for nitrate, helping households overcome this barrier is cheap. We asked respondents about their willingness to pay for the program and found that the average household was willing to pay as much as US$13 for a program that would cost the state roughly $5 to implement.

However, we could not determine whether our outreach decreased households’ exposure to contaminated drinking water. It’s also not clear whether people would be as willing to test their well water in states such as Wisconsin or Oregon, where testing would cost them up to a few hundred dollars.

As of 2024, just 24 states offered well water testing kits for at least one contaminant that were free or cost $100 or less. And while most states offer information about well water safety, some simply post a brochure online.

The upshot is that rural households are bearing the costs associated with unsafe well water, either through health care burdens or spending for treatment and testing. Policymakers have been slow to address the main source of this problem: nitrate pollution from agriculture.

In one exception, state agencies in southeastern Minnesota are providing free well water quality testing and offering a few households filtration systems in cases where their wells are laden with nitrate from local agricultural sources. However, this effort began only after environmental advocates petitioned the EPA.

If state and federal agencies tracked more systematically the costs to households of dealing with contaminated water, the scale of the burden would be clearer. Government agencies could use this information in cost-benefit assessments of conservation programs.

On a broader scale, I agree with experts who have called for rethinking agricultural policies that encourage expanding crops associated with high nutrient pollution, such as corn. More restoration of wetlands and prairies, which filter nutrients from surface water, could also help. Finally, while the Environmental Protection Agency can’t force well owners to test or treat their water, it could provide better support for households when pollutants turn up in their drinking water.