Insurance Stories: International Women’s Day

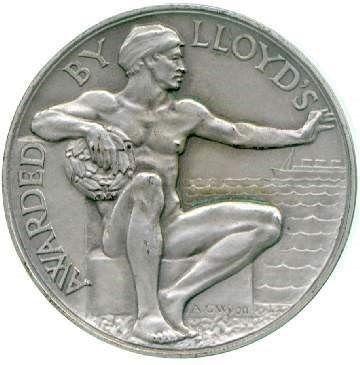

To celebrate International Women’s Day 2022, we take a look a collection of inspirational women whose acts have been recognised through Lloyd’s of London and those who broke new ground in the market.

Ethel Langton: The Lighthouse

“Lloyd’s of London have decided to confer on Miss Ethel Langton, the Lloyd’s Bronze Medal for Meritorious Services as an honorary recognition of the courage and endurance displayed by her.”

In 1925 and on her 15th birthday, Ethel was left home alone at the St. Helen’s Fort Lighthouse. Her parents had gone shopping but were unable to return due to the worst storm in living memory.

The lighthouse overlooked one of the busiest stretches of water in the world and hundreds of lives would be put at risk if its light went out. When darkness fell, Ethel decided that ‘On this night of all nights, the lamp must shine.’

The oil-burning lamp was on top of a 20-foot tower, reached by climbing an exposed steel ladder. It had to be tended to daily and checked throughout the night.

In darkness, Ethel began climbing but once above the fort’s walls, the weather hit. She was soaked by the spray and blinded by the storm. Each rung became almost impossible to climb. Once at the top, she was so scared that she crawled on her stomach towards the lantern.

This continued for three days and nights through torrential rain. A freezing and tired Ethel had survived on little food that she rationed and shared with her dog.

Her actions undoubtedly saved many lives.

Elizabeth Owen: Bravery at Sea

21 recipients of the Lloyd’s War Medal for Bravery at Sea were announced in Lloyd’s List on 8th January 1942.

Among them was Elizabeth Owen, stewardess of the Irish mailboat St. Patrick which was bombed and sunk in June 1941 with the loss of many lives. Ms. Owen had already been awarded the George Cross for heroic conduct on the St. Patrick.

After the vessel had caught fire and broken in two, she groped her way through the darkness to the women’s berths on the lower deck, brought up five women and girls, and saw that they put on lifebelts. This meant that she did not have a lifebelt herself.

Ms. Owen then refused to take a place in the last lifeboat, choosing instead to jump into the sea to rescue a young girl. She found her and supported the child for two hours until they were rescued.

Another Lloyd’s medal winner announced that day was Richard Hamilton Ayres, second mate of a ship torpedoed in the Atlantic, and the only survivor after 13 days of 31 men who got away in a lifeboat. Twenty-four of the men died after seven days from exposure or drinking seawater, five were drowned when the boat twice capsized and another seaman was washed away after swimming to a rock on the Cornish coast.

“Undismayed by suffering and death, he kept a stout heart” said the official account of Mr. Ayres’ bravery.

Many others were awarded the medal on the same day, including a 16-year-old Thomas Roward Eagles. He was a ship’s apprentice who, under a hail of tracer bullets, continued machine-gunning an attacking aircraft and destroyed it.

Others to receive the Lloyd’s War Medal for Bravery at Sea that day include:

– Radio officer, John Husband Burnett, who when his ship was torpedoed, swam in a shark-infested sea to rescue his master.

– Bertram Charles Covill, acting able seaman-gunner, who returned to his sinking ship after she had been bombed and saved the chief engineer.

– John Patterson, able seaman, who though only 19, took charge of a lifeboat from a torpedoed ship, kept it afloat in immense seas for 53 hours, and saved 10 lives.

– Alexander Murray, mate of a small coaster attacked by aircraft who was instrumental in saving six men though suffering himself from many wounds.

The last to be announced that day was Alexander Macquarrie, third engineer of a ship shelled by a U-boat. Though wounded, he remained at the engine-room controls until he fainted from loss of blood.

Eugenie Matelot: Saving Life at Sea

The second woman to receive the Lloyd’s Medal for Saving Life at Sea was a Frenchwoman named Eugenie Matelot. Born in 1884, she married Alexandre Matelot, a lighthouse keeper based at Kerdonis off the Brittany coast.

On the 18th April 1911, Alexandre was cleaning an automated mechanism that turned the light but before he could put it back together, he became unwell with appendicitis and went to his bed in great pain. The nearest doctor was several miles away and his wife dared not leave his side. The couple also had four children to look after at the lighthouse. Their two other older children were away at the time, one in hospital, another at sea.

Alexandre died later that day. With dusk approaching, Eugenie kept vigil with her husband’s body but it was also vital the light was lit and kept turning. Although she could not put the mechanism back together, Eugenie knew enough about the timing of the light and with the help of her older children, aged 8 and 10, she managed to light the lamp and then manually push it around, keeping it going all night.

Despite her bravery, Eugenie Matelot was not entitled to receive her husband’s wages, nor was she eligible for any pension as his widow. This meant that she and her children were left destitute. A local man was so outraged by this that he wrote a letter to the French newspaper Le Figaro to ask for help for the family and their story spread like wildfire. This resulted in the family receiving a large cash sum. Many donations were made from the maritime community.

On 3rd September 1911, the British Consul and a representative of Lloyd’s of London travelled to Mme. Matelot and presented her with the Lloyd’s Medal.

Eugenie went on to be a successful lighthouse keeper in her own right. She died in 1935.

Lloyd’s: First Female Members

Margaret Alder was the first woman to enjoy lunch in the members-only Captain’s Room at Lloyd’s of London.

She and 44 other women officially became the first female members of Lloyd’s on the same day in November, 1969. Mrs. Alder was the only one to dine in the room as others declined or were unable to attend – ‘It was my husband’s idea. He has been an underwriter for more than 20 years and he has always been keen on having female members.’

Seen in the picture is Margery Hurst, founder of the Brook Street Bureau. She was one of the 45 women to be made members of Lloyd’s that day and said: ‘I joined because I believe that if women are to get equal rights they must take advantage of every opportunity available to them.’

Liliana Archibald became the first woman allowed to enter the Room in 1972. She said ‘I did not break down the barriers; they were broken down for me by the members of Lloyd’s in a very charming way.’

Mel Goddard (then with QBE) became the first female active underwriter in 1996 and Dame Inga Beale was named the market’s first female CEO in December 2013.

Stories from Paul Miller.

Paul is HFG’s in-house historian and is a History Ambassador for the Insurance Museum.

Click here to find our previous Insurance Stories on our blog.