Human rights and COVID restrictions: what South Africans are willing to give up

A man gets vaccinated at the recent launch by President Cyril Ramaphosa of a vaccination campaign

in Katlehong, Gauteng Province. GCIS/Flickr

South Africa’s constitutional democracy guarantees citizens certain basic human rights. But the regulations that attended South Africa’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic severely limited some of those rights. These include the right to freedom of movement and assembly, and the right to work or trade.

President Cyril Ramaphosa declared a State of Disaster in March 2020, and placed the country under lockdown, in a bid to combat the pandemic. The lockdown regulations (or “levels”) changed from time to time, becoming more or less restrictive. These included the controversial “ban” on alcohol and cigarettes during the level 5 lockdown, restrictions on leisure and social activities, the closure of schools and universities, restricted attendance of funerals and other gatherings and a curfew.

Because the need for the state to limit freedoms for the common good is likely to recur, it is crucial to understand how supportive the public has been of the suspension of their human rights and freedoms.

To find some answers, we (researchers from the Human Sciences Research Council and the University of Johannesburg) conducted a series of surveys between April 2020 and November 2021. The online surveys set out to find out how South Africans viewed the national lockdown, including their willingness to sacrifice some rights in the fight against the virus.

We found that most adults were prepared to sacrifice their rights to ensure the safety and health of all during the pandemic, averaging 74% across all five survey rounds. Cleavages emerged among the public over time, leading to polarisation in attitudes, but the lasting impression is of broad support for rights sacrifice as part of an ethic of care for others.

Read more:

Why human rights should guide responses to the global pandemic

These findings matter mainly because pro-sacrifice attitudes affect health protection behaviours. The survey shows that those favouring sacrifice are more inclined to be vaccinated, always wear masks in public, and are less likely to believe that lockdown regulations are too harsh. This is the kind of evidence that policymakers have required, using citizen voices to inform COVID responses.

The research

The research collected data from respondents aged 18 and over, using the #datafree Moya Messenger App developed by Datafree.

Five rounds of the survey were undertaken with different size samples, amounting to a total 45,418 respondents. The data are weighted to align with Stats SA’s demographic estimates based on age, population group and education. This allows the survey results to be broadly indicative of the attitudes and behaviour of the population.

Round 1 was conducted between 13 April and 11 May 2020 during stringent lockdown restrictions (level five and the early stages of level four).

Rounds 2 to 4 covered the periods of the different waves, during which the restrictions were either eased or tightened. Round 5 was completed between 22 October 2021 and 17 November 2021, during the least strident level 1.

In each round, respondents were asked about their agreement with the statement “I am willing to sacrifice some of my human rights if it helps prevent the spread of the coronavirus”.

Key findings

We found that the majority of South Africans were willing to sacrifice their rights in support of government efforts to fight the pandemic.

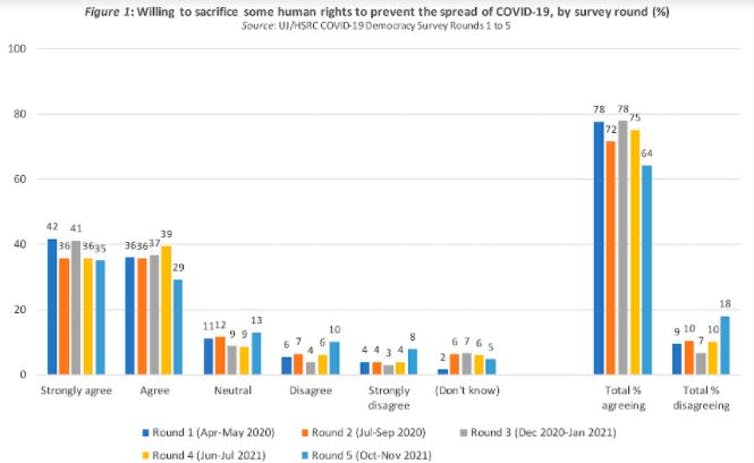

Data from our first round of surveying showed that 78% of people were willing to sacrifice some human rights if it helped reduce the spread of COVID-19 (Figure 1). As the country moved to lower lockdown levels, a decline in support occurred, falling to 72% over the July to September 2020 survey round.

However, following the beginning of the third COVID-19 wave, support returned to 78% in the third survey wave (December 2020 – January 2021). Similar willingness to sacrifice rights (75%) was observed during Round 4 (June – July 2021), coinciding with the emergence of the Delta variant and the move to higher alert levels.

In the latest survey round (October – November 2021), conducted after the third wave and during the least severe lockdown level 1, support for sacrificing rights was the lowest since the pandemic began at 64%.

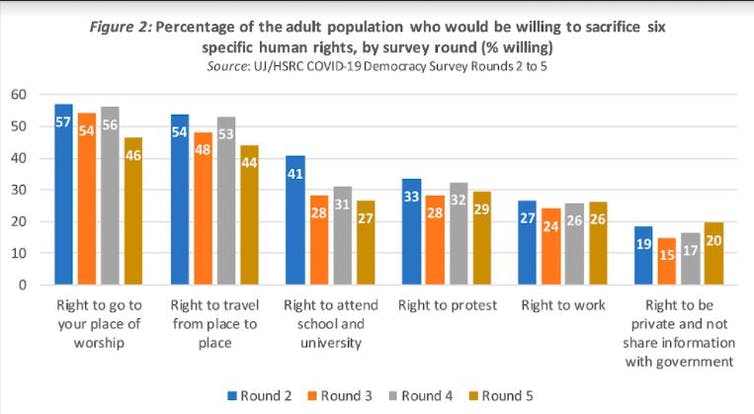

Beginning in Round 2, respondents were provided with a list of six freedoms they might be willing to forgo to stop the spread of the pandemic. Our results suggest that individuals differed on which human rights they would sacrifice (Figure 2).

In Round 2, 57% said that they would surrender their right to religious assembly, with a similar share (54%) willing to allow restrictions on their freedom to travel. 41% were willing to suspend the right to attend school and 33% the right to protest. About a quarter (27%) were willing to forgo their right to work, while 19% felt that their right to privacy could be limited.

It was only in Round 5 in late 2021 that we witnessed a decline in the willingness to sacrifice the rights to religious assembly and freedom to travel, by about 10 percentage points. Support for sacrificing the other rights scarcely changed.

A hierarchy of preferences, and a significant class divide was evident.

The largest declines in willingness to sacrifice rights were most evident among white adults, suburbanites, and those with tertiary education.

Better-off and better-educated people were more likely to sacrifice their freedom to gather for worship, travel and protest than their poorer counterparts. This speaks to differences in opinion on the nature and meaning of rights. Individual liberties appear to be most important to the wealthy. The poor tend to see rights within the context of social solidarity and the greater good.

Despite these societal differences, the message is one of social solidarity and willingness to accept short-term limitations of rights for the good of society.

Our research shows that political trust, and specifically confidence in President Ramaphosa, was one of the most important factors behind support for the restrictions.

Conclusion and recommendations

There can be a dark side to the otherwise positive findings of our study.

Read more:

Head of UNAIDS unpacks the knock-on effects of COVID-19. And what needs to be done

Such public health emergencies place immense power in the hands of executive leadership. Thus, there is a risk of leaders using them as an excuse for despotism. Thus, we make three policy recommendations to address the risks:

First, if the government wants people to trust it and comply with regulations, it must clearly communicate why they are necessary and allow participation in decision-making; to debate views on the laws and regulations that govern their lives.

Second, restrictive regulations must be evidence-based. They must also be temporary, subject to review and not discriminate unfairly, in keeping with United Nations principles on limiting rights. Blanket bans – such as that on tobacco – lead to lack of trust in leadership.

Third, civil society must actively keep an independent watch on what government does. It’s important to use accountability mechanisms such as Chapter 9 institutions, which defend the constitution, and strong, independent courts.

Narnia Bohler-Muller receives funding from various sources for projects conducted by the Human Sciences Research Council.

Benjamin Roberts receives funding from various government and non-governmental sources to conduct the annual round of the South African Social Attitudes Survey (SASAS).

Steven Gordon has received funding from the University of Witwatersrand. He is a Research Associate at the University of Johannesburg and a Senior Research Specialist at the Human Sciences Research Council.

Yul Derek Davids is a Research Director at the HSRC and receives funding from various government departments funding institutions for research at the HSRC.