evLYG Explained

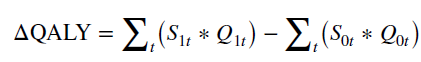

One concern when using quality adjusted life years (QALY) to measure health gains for cost effectiveness research is that QALYs “undervalue” health gains from life extension for people with serious illness or chronic disability. To see this clearly, take a look at the QALY formula (first formula below) and how it can be decomposed into changes in quality of life (Q) and survival (S) for a new intervention (indexed at 1) compared to the old (indexed to 0).

Note that the survival gains are only valued at the quality of life that the intervention can acheive (Q1t). Thus, survival improvements for patients who remain having a poor quality of life are devalued relative to those who woudl be in good or even perfect health.

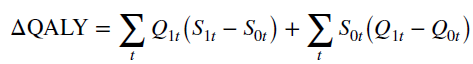

A paper by Campbell, Whittington and Pearson (2023) describes how the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) computes an alternative measure: equal value of life years gained (evLYG). I have described this approach previously here. evLYG can be calculated as follows:

On the right hand side , the second term is identical in both the evLYG and QALY equations, indicating that quality of life gains during the survival period of the first person are evaluated the same. However, under evLYG, survival gains are valued at some other number (Qt) which can be different from the quality of life value of the new treatment. Under the original evLYG approach proposed by Nord et al. (1999), survival gains are valued at perfect health (i.e., Qt=1). However, the Campbell et al. approach used by ICER, sets Qt=0.851, which is equal to the average utility of the general US adult population. Note that the ICER approach assigns lower evLYG than does the Nord approach.

Under ICER’s implementation of evLYG, the different in the way health gains are measured between evLYG and QALYs can be summarized as follows:

![]()

evLYG have the key advantage that survival gains to sicker patients are valued more (although less under ICER’s implementation than under Nord).

In fact, ICER’s assessment of 32 unique interventions using both evLYG and QALY found that in 66% of cases ΔevLYG>ΔQALY, and in 34% of cases ΔevLYG=ΔQALY. The mean percentage change between an intervention dyad’s incremental QALYs and incremental evLYs was 16%. In the interventions where ΔevLY > ΔQALY, incremental evLYs were 25% higher than incremental QALYs.

One key limitation of evLYG is that quality of life improvements during the ‘survival gain’ period are not captured under evLYG.

You can read the full paper here. It is a useful primer both on what evLYG is and how ICER has been using evLYG in its assessments.