Coverage with Evidence Development (CED) in Europe: Examining CED for medical devices

That is the topic of a new paper by Drummond et al. (2022). When medical devices receive regulatory approval, payers can make one of three coverage decisions: (1) approve, (2) reject or (3) coverage with evidence development (CED). Note that all countries approve medical devices based on safety and efficacy but only England, the Netherlands, and Belgium also rely on cost-effectiveness models as well to inform medical device reimbursement decisions. If CED is selected, there are two types:

(3a): Approved only in research (OIR). This means that the device is only approved for patients who are enrolled in a confirmatory post-registration study (PRS), or (3b) Approved only with research (OWR). This means that the device is approved for all eligible patients conditional on the fact that the manufacturer conducts one or more PRS.

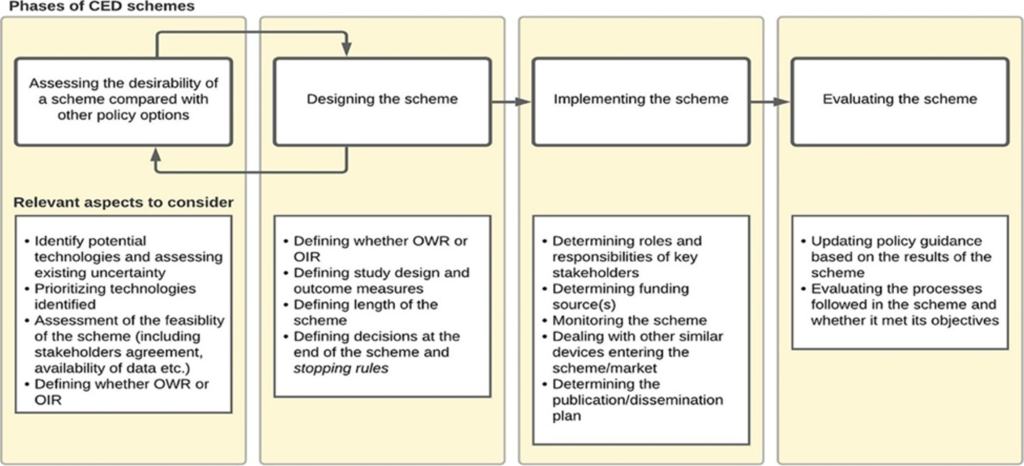

Implementing CED may be based on 4 phases discussed as outlined in Garrison et al. (2013) (i) assessing the desirability of a CED scheme, (ii) designing a scheme, (iii) implementing a scheme, and (iv) evaluating a scheme. The figure below summarizes this approach and I briefly summarize key considerations in each of these phases from the Drummond et al. 2022 paper.

Assessing the desirability: Typically occurs during the reimbursement process. For instance, “in France, the request to conduct a post-registration study (PRS) can be issued for any technology for which relevant evidence gaps have been identified during the initial request by the manufacturer for registration in the list of reimbursable products and procedures (LPPR). A request for a PBRSA is explicitly made by the Medical Device and Health Technology Evaluation Committee (CNEDiMTS) and, if accepted by the Ministry of Health, renewal of the registration in the LPPR (after about 3 years) is made conditional to the provision of new evidence by the applicant.” Formal assessment around the desirability of coverage with evidence development is often lacking; for instance there is no formal “value of information” analysis conducted. However, the need for CED may be influenced by key stakeholder requests such as clinical groups, hospitals or manufacturers. A appear by Grimm et al. (2016) provides a checklist of questions to determine the potential need for a managed entry agreements (MEA), which relate to the degree of uncertainty and if uncertainty could be resolved by an MEA at reasonable cost. “In some countries (i.e., England, France, Germany, and Belgium), a deliberative approach is taken based on pre-specified criteria, while in others (i.e., Spain, the Netherlands, and Switzerland), quantitative tools or checklists are used to select and prioritize the schemes. ”Designing CED Schemes. Key decisions here cover conditional approval type (i.e., OWR or OIR), the research question of interest, study methodology (i.e., RCT vs. observational), and study duration. Regarding the research questions, key topics could include not only a confirmation of the clinical efficacy but also (i) the durability of the efficacy impact, (ii) efficacy by patient sub-groups, (iii) impact of the learning effect on performance, and (iv) the rate of real-world uptake and conditions of use, (e.g., including potential off label uses; patient adherence rates). While RCTs are often preferred, for medical devices RCTs often are difficult to implement in practice (e.g., blinding may not be possible, patients may not want to enroll in the “control” arm once a treatment is approved) and may not be ethical. Another questions is whether the study should pre-specify the target outcome. While this makes sense in the clinical trial setting, the standard of care may evolve over time making fixed, pre-specified criteria difficult to implement in practice. Most studies to support CED last between 2 to 5 years, but Drummond et al. (2015) notes that schemes longer than 3 years may fall off the top priority list of decisionmakers. England’s commissioning through evaluation (CtE) schemes generally have a fixed duration of 2 years. Implementing CED schemes. One key question is who will fund these studies. In France, manufacturers provide funding for data collection and analysis for post-registration studies (PRS) and thus about 15% of all devices assessed for inclusion in the list of reimbursable products and procedures (LPPR) required a PRS. On the other hand, CED schemes in England and Germany are publicly funded and centrally managed and thus the number of PRS for devices were only 5 (England) and 10 (Germany) over one recent 5-year period. PRS design is complicated when new devices enter the market or new generations of the same product enter the market. Evaluating CED schemes. Retrospectively evaluating CEDs can be useful to (i) better design future CED schemes for other products and (ii) make any decisions based on the results of the CED scheme (e.g., should reimbursement be made permanent?; if so at what price?). The authors note that “Many devices are used in a hospital setting and are funded as part of a bundled payment for the procedure in which the device is used (e.g., a DRG payment).” Thus, if CEDs show that new devices not only are safe and effective, but also provide good value for money, the DRG payment may need to be adjusted more frequently.

What was the results of most CEDs?

Of the European schemes that ended between 2014 and 2019 and for which the results led to a final reimbursement decision, most resulted in the unrestricted and unconditional reimbursement of the device.

What do Drummund and co-authors recommend? They make 6 specific recommendations:

Define the purpose of the CED scheme in terms

of the uncertainty to be resolvedApply VOI where feasible, or at least VOI

principles Reflect the nature of the uncertainty in the study

design Balance scientific and practical considerations

when determining the length of CED schemes Define decisions to be taken at the end of the

CED scheme as early as possible Provide solid reasons when deviating from common CED principles

Appendix.

Five elements of good practice for performance-based risk sharing agreements for pharmaceuticals:

…(i) defining a strategy to guide use of PBRSAs for pharmaceuticals; (ii) ensuring they are used only where the benefit of additional evidence outweighs the cost of negotiating and executing the agreement; (iii) clearly identifying uncertainties in each reimbursement decision and design agreements to ensure that data sources and research designs are appropriate to address the uncertainties; (iv) implementing a governance framework that ensures transparency of process, and allows payers to act upon the additional evidence, including exiting from the agreement and potential withdrawal of temporary coverage; and (v) ensuring a minimum level of transparency of content, limiting confidentiality to those parts of the agreement that may be commercially sensitive (in particular, prices).