CHIR Experts Testify About Facility Fees Before Maryland General Assembly

By Karen Davenport & Rachel Swindle

In early March, CHIR experts Rachel Swindle and Karen Davenport shared findings from CHIR’s research on state-level facility fee reforms before House and Senate committees of the Maryland General Assembly. Both the House Health and Government Affairs Committee and the Senate Finance Committee were considering proposals to expand Maryland’s current consumer disclosure requirements, which apply to facility fees charged for clinic services, to encompass a wider range of services and outpatient providers. These proposals would also establish a study on the scope and impact of outpatient facility fees in Maryland. Following the hearing, the Senate Finance Committee amended the legislation by dropping the notice provisions and retaining the study requirement; once the full Senate approved that version, it crossed over to the House for consideration. The House has made further changes to the study specifications, which will require Senate action before the legislature adjourns.

You can view video recordings of both the House hearing and Senate hearing. The written statement that Swindle and Davenport filed with the committees follows.^

Introduction

In recent years, health care consumers, payers, and policymakers have brought attention to the growing prevalence of hospital outpatient facility fees in the United States. As hospitals and health systems expand their ownership and control of ambulatory care practices, they often newly charge facility fees for services delivered in these outpatient settings. Facility fees are an important element of spending on hospital outpatient services, which is one of the most rapidly rising components of health care spending. The growth in the amount and prevalence of these charges is important to payers and consumers, who face greater financial exposure as insurance deductibles increase and payers develop new benefit designs that increase patients’ exposure to cost-sharing, particularly in hospital outpatient settings.

Policymakers across the country and in Congress have begun to respond to this problem. Between November 2022 and April 2023, CHIR researchers examined laws and regulations on outpatient facility fees in 11 study states—Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Indiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, Ohio, Texas, and Washington—and conducted more than 40 qualitative interviews with stakeholders and experts. We continue to delve into this issue and are currently in the midst of assessing laws and regulations in the remaining 40 states. Our full 2023 report is available on our website.

Background

Facility fees are the charges institutional health care providers, such as hospitals, bill for providing outpatient health care services. Hospitals submit these charges separately from the professional fees physicians and certain other health care practitioners, such as nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and physical therapists, charge to cover their time and expenses. In general, public and private payers pay more in total when patients receive services in a hospital—including, importantly, hospital-owned outpatient departments—instead of an independent physician’s office or clinic.

This payment differential both encourages and exacerbates the effects of vertical integration in the U.S. health care system, as hospitals and health systems acquire physician practices and other outpatient health care providers. When a hospital acquires or otherwise affiliates with a practice, ambulatory services provided at the practice can generate a second bill, the facility fee, on top of the professional fees the health professionals charge. As hospitals expand their control over more outpatient practices, they can also exert greater power in their negotiations with commercial health insurers and extract even higher payments.

This growth in outpatient facility fees drives up overall health care spending, resulting in higher premiums. Our research also suggests that insurance benefit designs are increasing consumers’ direct exposure to these charges. Rising deductibles appear to be one factor. However, even when a consumer has met their insurance deductible, a separate facility fee from the hospital on top of a professional bill may trigger additional cost-sharing obligations for the consumer, such as a separate co-insurance charge on the hospital bill. Insurers also may require higher cost-sharing for hospital-based care than for office-based care, resulting in higher out-of-pocket costs than consumers otherwise anticipate for their outpatient care.

Consumers may question why they receive a hospital bill for a run-of-the-mill visit to the doctor. Hospitals maintain that these charges cover the extra costs they incur and services they provide—such as round-the-clock staffing, nursing and other personnel costs, and security—even though individual patients may not pose any additional costs or use the hospital’s services. In contrast, payers and a range of policy experts view facility fee billing as a way hospitals leverage their market power and take advantage of the United States’ complex and opaque payment and billing systems to increase revenue.

State Efforts to Regulate Outpatient Facility Fees

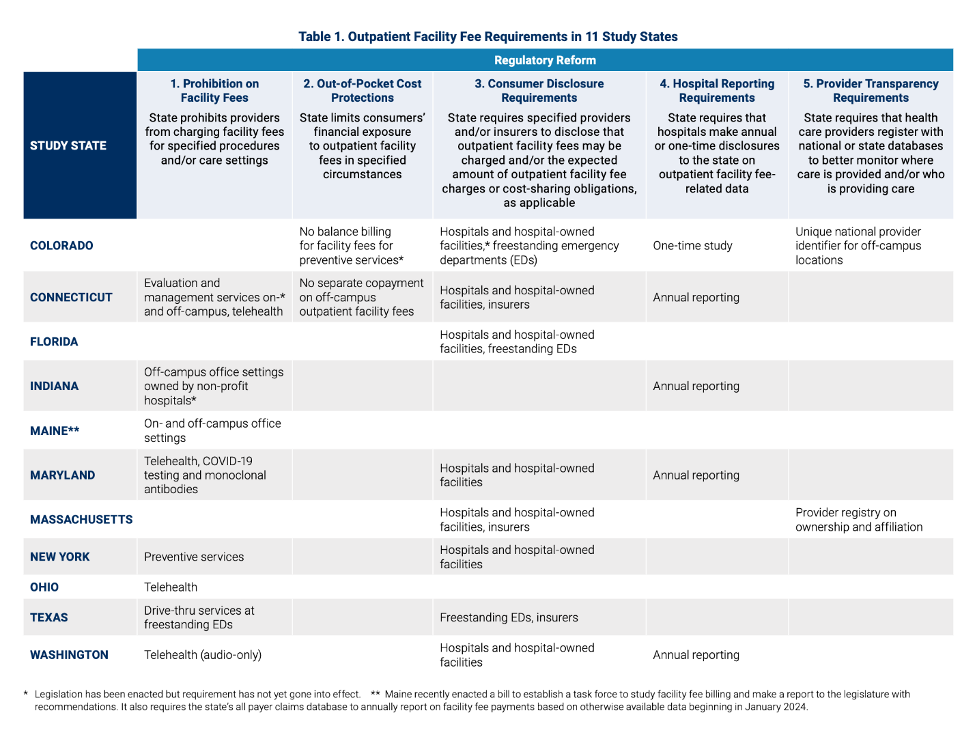

States are at the forefront of tackling outpatient facility fee billing in the commercial market. Our analysis of the laws and regulations in 11 study states demonstrates the range of reforms available (see Table 1). Specifically, we identify five types of reforms: (1) hospital reporting requirements; (2) consumer disclosure requirements; (3) out-of-pocket cost protections; (4) prohibitions on facility fees; and (5) provider transparency requirements.

Source: Monahan, C.H., Davenport, K., Swindle, R. Protecting Patients from Unexpected Outpatient Facility Fees: State on the Precipice of Broader Reform. (2023, Jul.). Georgetown University, Center on Health Insurance Reforms

Notably, since the publication of our report, Colorado and Maine have created commissions or task forces to study the scope and impact of facility fee bills on consumers and outpatient cost trends. These studies have been charged with providing state policymakers with recommendations for further reforms, reflecting how health care provider consolidation and escalating health care costs continue to pressure consumers and challenge policymakers. Similarly, Section 2 of HB 1149/SB 1103 requires the Maryland Health Services Cost Review Commission to examine the scope and impact of facility fees in Maryland and the implications of reducing or eliminating these fees. This study should shed much-needed light on the incidence of facility fee billing in Maryland, particularly given Maryland’s unique all-payer rate-setting system for hospital services, the impact these fees have on consumers, and possible policy responses.

Below, we describe the five approaches to facility fee reform we identified in our report. Many of these reforms are complementary and states have combined multiple approaches as they seek to protect consumers from these fees and control health care costs.

1. Hospital Reporting Requirements: Disclosing How Much Hospitals Charge and Receive in Outpatient Facility Fees

Five study states have adopted public reporting requirements to better understand how much hospitals charge and receive for outpatient care. Four states—Connecticut, Indiana, Maryland, and Washington—have enacted annual reporting requirements.

2. Consumer Disclosure Requirements: Notifying Consumers About Outpatient Facility Fee Charges

All but two study states require health care providers—typically hospitals and hospital-owned facilities and sometimes freestanding emergency departments—and/or health insurers to notify consumers that they may be charged a facility fee in certain circumstances. For example, Connecticut and Colorado require providers to disclose certain information about their facility fee billing practices upon scheduling care, in writing before care, via signs at the point of care, and in billing statements. Upon acquiring a new practice, hospitals in these states also must notify patients that they may be charged new facility fees. Other study states also require disclosures before care is provided and/or in signage at the facility. Some states require consumers to be more proactive, requiring only that information about facility fee charges be available online or provided upon request by hospitals and/or health insurers.

Of particular relevance to this hearing, Maryland requires hospitals to provide a pretreatment notice and a written range or estimate of facility fees for patients who schedule appointments for clinic services. HB 1149/SB 1103 would update this notice requirement in several ways. First, it would expand Maryland’s current notice requirement to additional critical services and revenue centers, including labor and delivery, physical and occupational therapy, diagnostic, therapeutic, and interventional radiology, and laboratory services. It would also revise the current notice requirement to ensure that patients receive both a written range and an estimate of likely facility fees. Finally, HB 1149/SB 1103 would apply this revised notice requirement to all hospitals operating facilities within the state of Maryland, even if the main hospital campus is located outside the state. Currently, out-of-state systems provide outpatient care at facilities they operate within Maryland but do not provide their patients with advance notice of potential facility fees; HB 1149/SB 1103 will ensure that patients receiving care at these facilities are also protected by Maryland’s pretreatment notice requirement.

3. Provider Transparency Requirements: Who Is Providing Care Where?

Colorado and Massachusetts have taken steps to bring more transparency to the questions of where care is being provided and by whom. Unfortunately, existing claims data often conceal the specific location where care was provided and the extent to which hospitals and health systems own and control different health care practices across a state. This makes it challenging for payers, policymakers, and researchers to effectively monitor and respond to outpatient facility fee charges.

Colorado requires every off-campus location of a hospital to obtain a unique identifier number (referred to as a national provider identifier or NPI) and include that identifier on all claims for care provided at the applicable location. While not a state in our study, Nebraska recently enacted a unique NPI requirement; Federal lawmakers and other states are considering similar proposals. One challenge Colorado has faced, however, is tracking the affiliations between different locations, all now represented by unique NPIs. Beginning in 2024, Colorado hospitals are required to report annually on their affiliations and acquisitions, which may help address this gap. Massachusetts does not have a unique NPI requirement but maintains a provider registry that includes information on provider ownership and affiliations among other data, enabling the state to better monitor trends in consolidation and integration.

4. Out-of-Pocket Cost Protections: Limiting Consumer Charges for Facility Fees

Two study states have adopted relatively narrow restrictions that limit consumers’ exposure to out-of-pocket costs while continuing to allow hospitals to charge facility fees in at least some circumstances. Connecticut prohibits insurers from imposing a separate copayment for outpatient facility fees provided at off-campus hospital facilities (for services and procedures for which these fees are still allowed to be charged) and bars health care providers from collecting more than the insurer-contracted facility fee rate when consumers have not met their deductible. More narrowly, health care providers in Colorado will be prohibited from balance billing consumers for facility fee charges for preventive services provided in an outpatient setting beginning July 1, 2024.

5. Prohibitions on Outpatient Facility Fees: Stopping Charges Before They Happen

Several study states have prohibited facility fee charges in some circumstances, although the scope of these laws varies significantly. Connecticut, Indiana and Maine prohibit facility fees for selected outpatient services typically provided in an office setting. Some states have more narrowly targeted facility fees for specific services, including telehealth services (Connecticut, Maryland, Ohio, and Washington), preventive services (New York), and Covid-19 related services (Maryland, Texas, and, during the public health emergency, Massachusetts).

Maine, which has the longest-standing prohibition among our study states, specifies that all services provided by a health care practitioner in an office setting must be billed on the individual provider form. This means hospitals cannot charge facility fees for office-based care, even when provided in a hospital-owned practice. We learned that some providers have narrowly interpreted this prohibition to limit facility fee charges for evaluation and management (E&M) services, but do charge facility fees for more complex procedures or, conversely, services where a physician is not directly involved at the point of care, such as infusion therapy for cancer treatment.

Indiana’s recently enacted law uses the same office-setting framework and more narrowly prohibits facility fee billing for off-campus facilities owned by non-profit hospitals. Connecticut currently bars hospital-owned or -operated facilities from charging facility fees for outpatient E&M and assessment and management (A&M) services at off-campus locations. Beginning July 1, 2024, this prohibition will extend to on-campus locations as well, excluding emergency departments and certain types of observation stays.

Further Reforms and Next Steps

Beyond the state reforms we highlighted in our 2023 report, states continue to consider additional strategies for understanding and addressing hospitals’ practice of charging facility fees for outpatient services. Pending legislation in Indiana, for example, would require hospitals and other health care-related entities to report corporate ownership relationships to the state Department of Health on an annual basis, while the Massachusetts Health Policy Commission’s most recent report calls for the state to require site-neutral payment for ambulatory services that are commonly provided in office settings.

Thank you for the opportunity to share our findings with you. As Maryland considers strategies for further protecting consumers from unexpected facility fee charges, it continues to stand in the vanguard of this important issue.

^This written statement has been reformatted from its original design to accommodate this publishing platform.