Can Canada’s P&C industry catch up to NatCats?

In much of Nova Scotia, last summer was hell. The Tantallon wildfire in May and June generated $165 million in insured damage, mostly for personal property, by the time the flames went out July 4.

In a normal year, residents would get a breather to start rebuilding. But 2023 proved different. A late-July rainstorm dumped two months’ of rain — between 200 and 250 millimetres — in just 48 hours. The claims poured in. And then, in September, the powerful post-tropical storm remnants of Hurricane Lee, added insult to injury by leaving thousands without power.

Before 2023, heavy rainy seasons would spur residents to think back to 1971’s Hurricane Beth for comparison. No longer. Nova Scotians aren’t even finished sorting the aftermath of 2022’s Hurricane Fiona.

“Everybody’s being really heavily taxed by these events,” said Glenn McGillivray, managing director of the Institute for Catastrophic Loss Reduction. “They are coming hot and heavy and very close together now, which never used to be the case…”

In past years, NatCats were more manageable.

“They didn’t really overwhelm anybody. We had lots of time in between losses where governments and insurers could make people whole again, and before we had to deal with the next one,” he noted. “That’s not the case anymore. We’re seeing really large events coming on the tails of each other, sometimes even overlapping each other. Restoration and recovery now often takes multiple years because of overlapping events.”

The increased pace is taxing the capacity of all industry players — insurance companies, independent adjusters, disaster restoration and other building contractors — as well as governments at all levels, said McGillivray.

“Whether you are issuing building permits, whether you are inspecting, or whether you’re doing disaster assistance, everybody’s getting stretched to the limits because of these events.”

Lengthening wait times

These losses are extremely disruptive and traumatic for insureds, who are waiting longer to get their homes rebuilt and their lives back to normal, said Greg Smith, president of Canadian operations at Crawford & Company.

At the same time, he added, “the local contracting community is limited by a tight labour market for skilled construction and trade workers, and the window for exterior work is only eight months of the year due to the severe winter weather conditions. This creates a compounding effect on a relatively small community, resulting in a work backlog that can last up to two years.”

Brokers, meanwhile, sit “at the absolute crux” between insurers and clients coping with risks triggered by rising NatCats, said Adam Mitchell, CEO of Mitch Insurance. For brokers, that means wearing two different hats when considering increased Cat losses.

“If I put on my business broker hat, it’s not actually a problem. None of our personal capital is at risk. It’s going to drive up premium. It’s going to drive up turmoil. It’s going to drive up people needing to shop and that’s what we do,” he told Canadian Underwriter.

“All of a sudden, there are more consumers of ice cubes, [so] we can sell more ice cubes. That’s just the market economics.”

However, wearing his human hat, he said it is clear consumers are experiencing increasingly challenging circumstances — and that is a serious problem.

“Storms are empirically getting bigger and more frequent and the damage [is greater]. It’s a really significant mess and something we need to…figure out how to navigate,” said Mitchell.

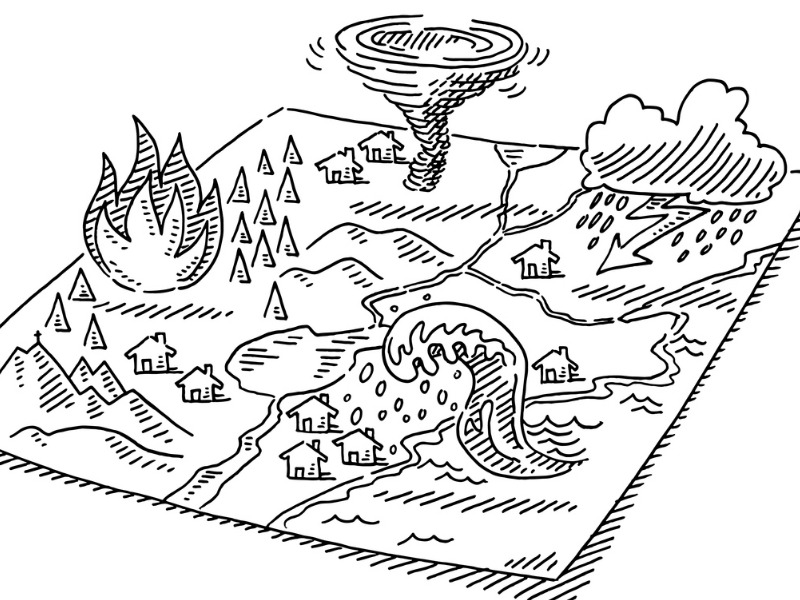

This story is excerpted from one that appeared in the November print edition of Canadian Underwriter. Feature image by iStock.com/FrankRamspott