A cyber side effect of the CrowdStrike outage

Although direct insured losses from the CrowdStrike software update error weren’t as large as expected, threat actors did try capitalizing on the resulting ‘blue screen of death’ errors to maximize damage, a CFC executive said during a recent webinar.

On the morning of July 19, endpoint security company CrowdStrike released an update to its Falcon sensor software, a lightweight software agent installed on an endpoint device that consistently monitors the behaviours of applications and processes. The sensor looks for “erroneous things that could be going on from an attacker behaviour perspective,” said Jason Hart, CFC’s head of proactive insurance, during the Aug. 29 webinar, Cyber expert panel: Anatomy of a global IT outage.

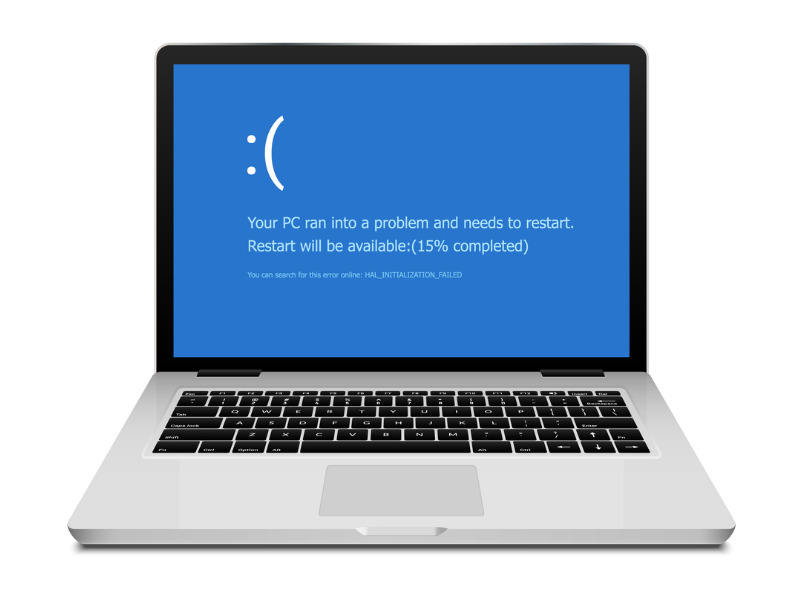

But that day, there was a critical error for any organization that had the Falcon sensor installed within a Windows machine, causing the blue screen of death. This reportedly affected 8.5 million devices.

What’s not commonly known, Hart added, is this wasn’t the first event this year for CrowdStrike. Two other events caused the same issue, one in March and one in April, that affected Linux machines with the Falcon sensor installed.

Reinsurance brokerage Guy Carpenter originally estimated global insured losses for the CrowdStrike event could be in the range of US$300 million to US$1 billion.

But several factors limited the scope of the damage, including that the event was not malicious and that terms and conditions in cyber policies limit insurers’ exposure to these kinds of incidents.

Lindsey Nelson, head of cyber development at CFC, noted during the webinar that on the day of the outage, there were reports about threat actors capitalizing on the blue screen of death errors and targetting businesses that were in vulnerable situations.

Disinformation reigns

“Everyone’s in a panic, organizations of all sizes. Their systems are down so that they’re going to align or believe anything that they potentially see,” Hart said.

“So, what we were actually seeing in the wild was pretty genuine emails, emails with the domain name being spoofed as CrowdStrike and ultimately trying to get predominantly SMB/SME [small and midsize businesses/small and medium-sized enterprises] to engage with the threat actors for assistance,” Hart said.

Doing so allows threat actors “to start installing additional types of malware or backdoors within those devices to later…cause another form of attack method…”

Hart reports CFC was able to send out 46,000 app notifications to its insured base, “and the read rate was extremely high.”

What can businesses do to protect themselves?

Hart said the simplest thing for an organization of any size is to determine the impact on particular systems and data.

“In the event something was to happen, what system, what data, if you could not access, would cause an impact based on one hour, two hours, half a day, a day, a week?” Hart asks. “You could literally just mind map this out.”

This provides a baseline level for organizations, that can then look at potential scenarios and consider options. It’s also important to have a plan in place, Hart said, adding that CFC even has pre-templated incident response plans that can be used.

“[After] an event, everyone’s in a panic,” Hart said. “But I can assure you…having a clearly defined plan — what are you going to do in the event of different scenarios — it makes you really prepared and that’s the key.

“When you’re not prepared, you will start making other mistakes,” he said. “The attackers, the threat actors, know this, and then will abuse that.”

Feature image by iStock.com/Kolonko