How much EV range do you really need?

Electric car range is one of the top concerns car buyers have when considering whether to make the switch to an EV — a concern so profound, the term “range anxiety” was added to the dictionary to describe it. But just how much EV range is enough? How much range do you actually need? The answer differs for everyone, and we’re here to help you figure it out.

The problem is that, like most things in life, we judge a situation based on our past lived experiences. We’re used to thinking about cars in internal combustion terms: Quick fill-ups, gaining hundreds of miles of driving range. You’ll make dozens of trips, perhaps over weeks, on that one fill-up. That’s what “normal” feels like to most of us. So, an electric car with a range of anything less than several hundred miles seems … scary, impractical.

But electric cars can’t be thought of like that. They don’t work the same way as gas cars — “several hundred miles” is the wrong context. Even with internal combustion, it’s rare that we utilize all that range in one sitting.

A gas-powered car has a marvelous convenience factor: a vast reserve of energy in a tank that can be quickly and occasionally replenished. But an EV has a convenience factor, too, it’s just different: You replenish the battery in many sips rather than one big gasoline gulp, and you do it from the comfort of your own garage. That might not sound like an advantage — until you’ve experienced the smug pleasure of driving past gas stations, saving $50 or $100 on fill-ups you no longer need.

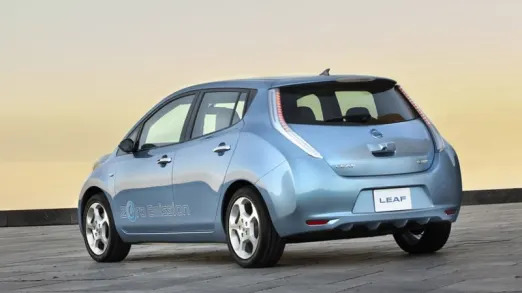

When the Nissan Leaf was introduced to the world for the 2011 model year, it had an EPA range rating of just 73 miles — and as a practical matter had less range than that when charged to just 80% as recommended for battery longevity. Nissan pointed out that the average daily commute at that time was less than 35 miles, which could easily be replenished in an overnight charge. But many thought the first-generation Leaf sounded like a science experiment.

Except it wasn’t. It just required a different way of seeing what a car can be.

We Americans tend to buy cars based on extreme use cases. We buy SUVs but don’t go off-road. We buy trucks but use them as cars. We want the ability to take a long cross-country highway trip, but might only do that once a year. That original 73-mile Leaf obviously couldn’t road-trip, but it was a clever commuter. When buying an electric car — when buying any car, really — it is important to confront what your actual use case is, not what you hope or imagine it to be.

So how much electric car range is enough? For you? Here are questions to ask yourself.

How far do you really drive in a day?

If you’re considering an EV, first do some research — on yourself. Get a notepad and pen, and log your mileage for a few days. For a week. For a month. How much do you really drive in a day? Is it something like the commuting average that Nissan cited? Or more like 100 miles? Even 200 miles? Do you actually do that much driving day-in, day-out? Be honest.

For some broader context, on average, Americans drive 14,263 miles per year, according to the Federal Highway Administration. Which breaks down to 1,188 miles per month — or 40 miles per day. (A stat that grew a smidge since Nissan cited 35, but by now it may have shrunk again given our post-pandemic work-from-home habits.) But let’s say the average is 40.

So, is your daily mileage below that average, or at it? Then you’ll love an EV. Are you over average? An EV will probably still work great for you. Read on.

Try this formula

Many automakers recommend charging your EV to 80% for daily use and for the sake of battery longevity, reserving a 100% charge for those times when you know you’ll need maximum range. Likewise, not typically letting your battery percentage fall below 20% is also good battery longevity hygiene, and it ensures you’ve got some reserve range if needed, which should provide some peace of mind. So, setting aside that ceiling and floor leaves a typical daily operating range of 60% of a battery’s capacity.

Now pick an EV you’re interested in, and look up its EPA range estimate at fueleconomy.gov. Ignore the government’s “MPGe” numbers, which for many buyers are not particularly useful, and focus on the range ratings. Now let’s use a Mustang Mach-E AWD in GT trim for this example. Its EPA rating is 270 miles, so 60% of that is 162 miles.

Consumer Reports testing found that cold weather can easily cost an EV 25% of range. (Of course, cold weather is hard on gas mileage in conventional cars, too.) If you live in a cold climate and want to be even more conservative with your calculations, then think of our hypothetical Mach-E’s range as 120 miles in bad weather.

If your daily driving routine is less than this, you’re going to be perfectly comfortable with that car.

Also, keep in mind that many EVs today are excellent at meeting or even exceeding their EPA range, thanks to regenerative braking (the Mach-E is a good example of this).

Next question: Do you have a garage?

Yes, you do have a garage, carport, etc.? Sweet. Conversely, charging an EV is obviously far more difficult for, say, apartment dwellers who don’t have a dedicated space or access to a 240-volt outlet, and maybe the time is not yet right for those people to buy an EV.

There is a lot of talk these days about public charging infrastructure (or lack thereof). It seems we want DC fast chargers to be as plentiful as gas stations (there we go again, applying internal combustion context to EVs). And we want to be able to charge fast, fast, fast. But ideally, you’ll want/need to use public charging only rarely if ever, as it presents drawbacks in terms of time, will cost more than charging at home, and rapid charging perhaps has long-term implications for battery longevity. Home replenishment is an EV’s party trick. Read on.

How long is your car typically parked?

We’ll return to the Nissan Leaf for this example, in this case the base 2024 Nissan Leaf S. The Leaf is one of the most affordable EVs currently on the market, at $29,280. That’s before the $3,750 federal tax credit it’s eligible for.

The Leaf S has a relatively modest range of 150 miles (for daily driving, that’s more like 90 miles based on our 60% formula) with a relatively modest 40 kWh battery pack. Plugged in to a 240-volt outlet, a Leaf S will receive a full charge in about eight hours, and replenish a 60% use in even less. In other words, it’s easily refreshed while you sleep. A Tesla will similarly take about 8-10 hours. Park the car at night, pop it on the charger, enjoy your evening and a good night’s sleep, and in the morning you’re topped off and good to go. What could be easier?

But bigger isn’t always better with EV batteries

There’s an important reason why you should be realistic about your daily driving needs and overall use case. If you tell yourself that you want a range of many hundreds of mile on a charge, you for starters are going to be paying a lot more to purchase your car. Just five or six years ago, battery costs made up nearly half the cost of an EV. They are now closer to about a third of the cost, and are projected to continue falling in the years ahead. But if you don’t need hundreds of miles of range on a daily basis, then why pay for it? Beyond the unnecessary cost of buying capacity you don’t need, a bigger battery will require longer charging times.

Now, let’s talk about long highway trips

How often do you road-trip, say for a vacation? Once a year? Twice a year? Five times? In a 2018 study, the University of Michigan’s Transportation Research Institute found that EV owners saved about $600 a year powering their vehicles, spending $485 on electricity vs. $1,117 for a gas-powered vehicle. But that study was based on gas prices four years ago — the savings would be far greater at today’s higher gasoline prices. And this doesn’t even take into account the savings EV owners enjoy from reduced maintenance costs when compared to an internal combustion engine. Ask yourself if it would make sense to drive an EV most of the time, then use all those savings to rent an ICE car for that rare long-distance road trip.

Public chargers are becoming far more common along major highway corridors, if you’re willing to do longer layovers and carefully plot your route. But this is a situation for which “range anxiety” is still a reality.

Best of both worlds

You don’t have to leap into the EV world without looking back. You might find you can ease your range concerns by simply hedging your bet.

More than half of American households own two or more cars. The best scenario for buying an EV is if you are among that multi-car majority. We’re convinced that virtually every two-car family in America could replace one of their ICE vehicles with an EV, and they would gain a powerful mix of capabilities. One car saves gas, the other can be employed when range is a concern. (Interest in hybrids is also surging right now as buyers seek to hedge their bests by having internal combustion and battery propulsion in the same car.)

In the two-car-family situation, we can practically promise you that you’ll find yourself driving the EV most of the time. And you’ll never again have to ask how much EV range is enough range.

Related video: