25 years of supporting buy to let: How the market has transformed

The growth of the private rented sector: Was it led by supply or demand?

There’s been a lot of talk over the years about landlords buying up properties at the expense of first-time buyers getting on the ladder, suggesting that landlords are ‘forcing’ people to rent rather than buy. And, as the chart below shows, there is no doubt that the private rented sector has been the main growth tenure since the 2000s.

However, our experience and knowledge tell us that the real reasons for the growth in the private rented sector are varied. That’s why, despite recent government efforts to curb the growth of the private rented sector in favour of home ownership, we think private renting is here to stay and will continue to grow into the future.

The reality is, many people on both low and high incomes need and want to rent.

So why has the private rented sector doubled in size?

Looking back at the changes in the private rented sector since the late 80s and early 90s, we believe the drive to increase renting in the UK came initially from the Conservative Government under Thatcher, and demand for rental homes has been fuelled by various different policies and world events ever since.

The catalyst for change was the selling off of around 2.8 million council houses, which is almost half of our social home stock. Once owned, these properties were then either passed onto future generations or sold and, according to a report from Inside Housing, around 40 per cent of these are now rented privately.

And, as the chart above shows, although there has been some decline in home ownership, the biggest proportional fall versus the growth in the property redress scheme is undoubtedly social housing.

With social housing availability almost halved over the last 40 years, people on benefits still need somewhere to rent. Just under 900,000 households renting privately are currently on benefits and, according to the official waiting lists, there are over a million on council waiting lists – although the National Housing Federation suggests this could be as high as 1.6 million. They estimate there are 1.5 million people in need of social housing who are currently living in the private rented sector.

Fast forward to the late 1990s and more demand for rented housing was added through Labour’s 1999 pledge, setting a target of “50 per cent of young adults going into higher education in the next century.”

Although this took until 2019 to achieve, there’s no doubt that the rapidly-growing student market required huge numbers of homes for students to rent privately – either from individual landlords (including investment-savvy mums and dads), institutional investors or from universities themselves.

And new demand for rental property kept coming. As the European Union added more member states, freedom of movement allowed more foreign nationals to come to the UK. One early report estimated this would increase net immigration by 5,000 to 13,000 per year, however, when most EU countries imposed controls in the early 2000s, it meant those that didn’t – Britain, Ireland and Sweden – ended up with the lion’s share of migrant workers, estimated at millions.

Economic crash drives demand

One unexpected cause for growth that we noticed – and it’s rarely talked about – is the 2007/8 credit crunch, which had quite a significant impact on rental demand.

By 2008/9 in England, the private rented sector accounted for approximately 14 per cent of households, with 68 per cent being owner occupiers and 18 per cent of households delivered by the social sector. This was a 40 per cent increase in the size of the private rented sector since the early 2000s.

As the earlier chart shows, the credit crunch was the next big driver of market growth and by 2016/7 the proportion of homes provided by the private rented sector had risen to 20 per cent – an increase of over 43 per cent in just eight years.

Since then, tenure proportions appear to have settled and it’s perfectly normal to see a plateau after a period of growth. By 2019/20, owner occupation represented 65 per cent of households – a small rise – with the private rented sector at 19 per cent and the social sector at 17 per cent.

And the rental market has remained buoyant, which is no surprise. Although three regions – London, the South and the South East – saw house prices continue to rise in line with inflation, most areas hadn’t seen big increases until this last year.

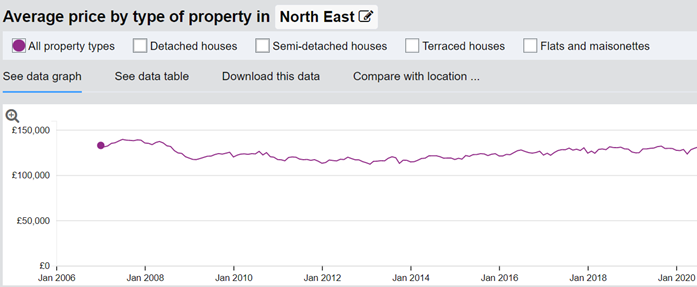

The North East is a case in point. At the start of 2021, the average house price was just one per cent higher than in 2007, 14 years earlier. The chart below shows how prices fell in the credit crunch and hadn’t actually recovered until this year.

If prices aren’t rising, there’s little incentive to buy and tenants are more likely to remain in rental accommodation. We believe this is a key reason why, in areas that have actually become more affordable, we’ve still seen a decline in the numbers of first-time buyers.

In addition, many regions around the UK saw property prices fall from 2007 through to 2013 – and beyond. Few first-time buyers would be brave enough to buy in a falling market that wasn’t showing any signs of improving and, as a result, they carried on renting.